Colville Landing, or as it was originally known, Colville Landinga, was named after the Hudson’s Bay Company’s S.S. Colville which plied the waters of Lake Winnipeg for many years. It in turn was named after two of the most important figures in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s history, Andrew Wedderburn Colville, and his son Eden. The former served for some time as Deputy Governor of Hudson’s Bay Company, and the latter served as Governor of Rupert’s Land.

Colville Landing was one of a number of steamboat docks and landings that developed in the 1870’s and 1880’s along Manitoba’s rivers. The Anson Northup began the era of steam navigation in Manitoba in 1859, proving that steamboats could operate on the shallow inland waterways of the prairies. The Anson Northup was succeeded by numerous larger and more powerful rivals, which pushed navigable limits of rivers and lakes 0f the Northwest to their maximum. It was not long before steamboats could be found not just on the Red River and Lake Winnipeg, but on the North Saskatchewan, the Qu’Appelle, and even the headwaters of the Assiniboine. Increasingly after 1859 they superseded the older methods of transport in the Northwest, the canoe, the York boat, and the Red River cart. They could carry goods and people quickly and reasonably safely, and, as long as wood was readily available, cheaply too. Moreover they could carry much heavier and bulkier goods into the interior than canoe, cart or York boat could. In Bishop Tache’s memorable phrase the Anson Northup “inatsgurated a new era for the trade of (the) Red River colony. ” ln time steamboats would revolutionize trade far beyond the parochial limits of the Red River settlement.

The Hudson’s Bay Company was very quick to see the potential of steamboats in the interior. Sir George Simpson and the Hudson’s Bay Company first guaranteed the Anson Northup five hundred tons of freight annually, and then purchased the boat themselves. It was to meet an untimely end during the winter of 1861-62, sinking at its winter dock on Cook’s Creek.

During its brief catered the Anson Northup, of as it was renamed the Pioneer not only proved the value of steam navigation in the Northwest, it also in involved the Hudson’s Bay Company in it. During the 1860’s the Company increasingly left the Red River traffic to other concerns, but in 1872 they embarked upon a scheme of supplying their posts on the North Saskatchewan with goods shipped by steamboat from their warehouses at Upper and Lower Fort Garry via Lake Winnipeg.

During the winter of 1871-72 workmen at Lower Fort Garry constructed a screw steamer: an interesting technological advance over the side and stern paddlewheel boats which had dominated steam navigation until then. Launched by Miss Mary Flett and christened with the traditional bottle of wine, the Chief Commissioner 18?2 proved to be a great disappointment.

Its shallow drought made it unsuitable for navigation on Lake Winnipeg’s rough waters, its boiler and other machinery caused problems, and its design and construction were amateurish Nevertheless the Chief Commissioner continued to steam to Grand Rapids and other points on Lake Winnipeg until 1875 when it was dismantled. Its hull was turned into a floating warehouse at Lower Fort Garry, and its machinery was transferred to a new steamboat the S.S. Colville which the Hudson’s Bay Company was having built at Grand Forks by Captain J. Reeves.2 It proved to be much more successful than the Chief Commissioner, and soon the Hudson’s Bay Company was developing its trade through Lake Winnipeg into the North Saskatchewan area.

They did this by setting up a rather intriguing hybrid form of transportation consisting of steamers and a tramway. In 1874 the Hudson’s Bay Company had a steamboat built by Captain Reeves on the North Saskatchewan called the Norlhcole, which was to achieve fame later at the Battle of Batoche.3 Thus between the Northcole and the Colville goods could be transported as far as Grand Rapids and then carried past this obstruction to another steamboat on the North Saskatchewan. Originally goods passed over a 3 1/2 mile dirt wagon road, but in October 1877, the Company built a narrow gauge tramway or railroad to connect the lake and the river. Constructed by Walter Moberly, the Grand Rapids Tramway consisted of “Light rail laid on ax-hewn crossties to a gauge of 3’6” (it) conveyed four-wheeled, horse-drawn tram cars which could haul up to four tons of cargo each.”4 It was also the first railroad to be operated in the Northwest.

By 1878 the Hudson’s Bay Company had an integrated transportation route stretching from the mouth of the Red River to Fort Edmonton. The Company had great expectations for it, particularly when it seemed as if it might be possible to further integrate this transportation route with the planned transcontinental railway. By the late l8?0’s railroad construction had come to Manitoba: the Pembina Branch of what became the C.P.R. was surveyed and graded, and track laying began in the autumn of 1877. This line was surveyed from the International border to Selkirk, and plans were made to have it intersect with the proposed mainline at Selkirk.

This mainline was not complete. It existed only in surreys and disconnected sections, nor had its course been completely settled upon. At the time, however, it was thought that it should cross the Red River at Selkirk.6. A railway line reached East Selkirk from St. Boniface in 1878, and the Hudson’s Bay Company soon saw its significance for their steamboat operations. Until this time the Company had used Cook’s Creek for wintering their boats and Lower Foft Garry as their warehouse and docking facility. The railway connection at East Selkirk, and the possibility that the main line might cross the Red River at Selkirk, caused a re-evaluation of the location of these operations.

In the vicinity of Selkirk the Red River creates two inlets of water, one on either side of the river, the East and West Sloughs. Both offered good harbour facilities and the potential for further development. The Hudson’s Bay Company chose to develop the East Slough as their warehouse and trans-shipment point for goods destined for the Saskatchewan River, and as the harbour and docking facility for the steamboats that would carry goods up to Grand Rapids, in particular the S.S. Colville.

Charles John Brydges, the Hudson’s Bay Company Land Commissioner between 1879 and 1882, interested himself in the question. In a letter sent by Brydges to William Armit, Secretary to the London Committee, dated May 4, 1880 Brydges states: “I go today with Mr. McTavish to Selkirk to see if arrangements can be made for a warehouse to ship goods on to the “Colville” from the railway. Mr. (James) Grahame (the Chief Commissioner) and I have fully discussed this matter and we quite agree as to what is wanted if it can be arranged.”T Six days later on May 10, 1880 he wrote again to William Armit and gave a progress report.

I went last week, by arrangement with Mr. Grahame, to Selkirk to arrange about a landing place for the “Colville” on the east side of the river. Mr. McTavish went with me, and we found that very good arrangements could be made. The Govt. have agreed to put a track to the water’s edge, where a warehouse can be erected, and then all goods for the Saskatchewan and Lake Winnipeg districts can be sent direct to that warehouse. When the Thunder Bay line is opened, it will be extremely useful, and save a great deal of handling and extra expense.

That fall the government of Canada had a short spur line built into what became known as Colville Landing from the rail-line at East Selkirk, a distance of two miles. Mr. David Douglas was the contractor and he had the spur line built in record breaking time. The work had started on May 12, 1880 and by July 20, 1880 it was completed and termed to be in very good condition.

There was an article in the Manitoba Free Press about one month before the project was completed, (June 15, 1880) which read, “Mr. D. Douglas, man in charge of the spur line at East Selkirk, received a blow to the face from the pump of the hand-car. The car was in motion, and Douglas attempted to get on and the pump hit him in the face, knocking him 12 feet from the track, not seriously hurt. “

Another article in the Manitoba Free Press, dated July 20, 1880, indicated that: “The Hudson’s Bay Company “Floating Warehouse” will be taken to the end of the spur line this evening. “

This spur line was later handed over to the reorganized Canadian Pacific Railway in Feb. 1881 along with the Pembina Branch, and 647 miles of trunk line.l0 Over the winter of 1880/1881 two buildings were moved from Lower Fort Carry to Colville Landing. In yet another letter from Brydges to Armit dated 6 Sept. 1880, Brydges states that “Arrangements have been made for putting two of the warehouses now at the Stone Fort (Lower Fort Garry) at the end of this track, so as to save as much as possible the cost of handling and transport for goods going up the Sask. River and furs coming down from the same country.ll Which warehouses or buildings these were is a matter of some conjecture. James Grahame in a letter to William Flett dated April 23, l8?9 suggested that the “wooden warehouse alongside the front gate of Lower Fort Garry” be moyed to the “steamboat landing.” A certain Mr. Clarke offered to tear down ,,a portion of the Fort walls” so that this building could be dragged on skids to its new location.12 This warehouse 58 was originally built as a barracks for soldiers from the Wolseley Expedition stationed at Lower Fort Garry in 1870.

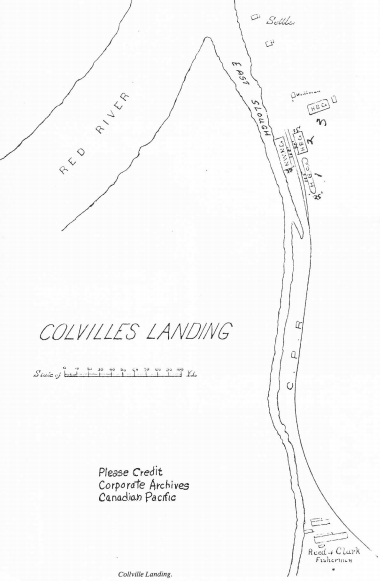

Thereafter it was used as a storehouse. Archaeological excavation of its original site indicates that the barracks was built on a foundation measuring 32 feet by ’72 feet which corresponds fairly closely with the Hudson’s Bay Company building No. 2 shown on the C.P.R. surveyor’s map (see Map), which is listed as being 70 feet by 35 feet. On the other hand, as Gregory Thomas has pointed out in his study of the lower Fort Garry landscape. a photograph. dared 1883, exists which shout a roof where this warehouse was situated, indicating that either the photograph is incorrectly dated or the barracks / storehouse building was not moved to Colville Landing.13. In this regard it is interesting to note that Crahame discusses moving the barracks / storehouse to a new site a full year before Brydges had gone out to choose one. This would tend to suggest that the photographic evidence is correct, and the Wolseley Expedition’s barracks were not moved to Colville Landing. Other observers, notably Robert Watson and George Ingram, however state that the barracks were Moved.

If the barracks building was not moved then at least two warehouses from the “industrial area” around the creek mouth just south of Lower Fort Garry were moved to Colville Landing that winter, and as James Grahame points out the hull of the Chief Commissioner, which had been serving as a floating warehouse at the fort, too. In his letter to William Armit previously mentioned he states that:

I found the two Buildings that had been moved from Lower Fort Garry in position and the Steamer “Colville” ready for service …

On examination of the Hull of the old Steamer “Chief Commissioner”, which had been converted into a floating Warehouse, we found that it was so much decayed as to be unsafe afloat any longer and I decided on having her hauled out of the water and converted into a Storehouse, which can be done at little cost. This is better than breaking up the old Hull as it is covered with a good shingle roof and in its converted state will be of service for some Years.l5

He also had a freight shed and shipping wharf built on piles along side of the water at a cost of $3,000.16

Referring to the map the Chief Commissioner’s hull would seem to correspond with building No. l, and the shipping wharf and freight shed with the building listed as belonging to the Northwest Navigation Company (or NWN Co. on the map).

The company also maintained a retail store at Colville Landing, and like the wharf it obviously was built with a view to more than economy. The Manitoba Weekly press and Standard on March 25, l88l described the store thus:

The large and handsome store of the Hudson’s Bay Company, at the end of the spur track, is nearly completed and is one of the finest and largest in the Province outside of Winnipeg, and is fitted up in elaborate style, the object of which is, no doubt to be able to supply the wants of the vast amount of emigration which will undoubtedly avail itself of this route to the wheat producing lands of the North-West.17

Problems were already developing for Colville Landing that were to interfere with its value to the Hudson’s Bay Company. James Grahame remarked that they were having “considerable trouble” because of the “… awkwardness of the Collector (of Customs) who will not allow our Northern Freight to go on from St. Boniface to Selkirk unexamined for want of a Customs Official at the latter place to check the Packages on arrival.” As a result, Company goods had to be unloaded from railway cars at St, Boniface, and then reloaded again. Grahame hoped that Brydges would be able to convince the federal government to do something about this, but as it turned out nothing was done.l8

Instead, by the following year the situation was if anything worse. Brydges in a letter to William Armit dated June 10, 1882 complained that:

The condition of railway matters between St. Paul and the end of the C.P.R. track is simply deplorable … Out of 2,635 packages of goods shipped from England between the middle of January and the beginning of May for the Hudson’s Bay Company for the Red River District, only 1,230 have arrived – no regard to dates of shipment – some of the late shipments in first … Goods for the first shipment up the Saskatchewan have been in the yard here for a good many days. and although ordered down to Colville Landing were never sent, but yesterday by accident our people found out that the cars had been unloaded alongside the track and lay exposed on the prairie. The results is that the steamer sails without these goods which ought, to reach their destination, to go by the first trip of the boat. t9

Despite these problems the Company continued to operate its store and warehouses at Colville Landing until 1883 at least. In fact two account books for 1882-83 listing some of the expenses and transactions taking place at Colville Landing still can be found in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Archives.2o Two brief notes in the Selkirk Herald for 1883 give us at least the names of two of the Managers of Colville Landing store. On July 27, 1883 the newspaper mentioned that a Mr. E. Turner, who had run the store for three weeks while its regular manager Mr. Mowatt had been away, had returned to his position in the company store in Winnipeg. Apparently during his stay he “paid frequent visits to Selkirk, and made many friends here, who would like to have had his stay made permanent.” His friends in Selkirk got at least part of their wish, when later that summer on Aug. 10, 1883 it was reported that Mr. J.D. Mowatt had been transferred to Fort Alexander and that Mr. Turner would replace him at Colville Landing.2l Even Mr. Turner’s personal popularity could not save Colville Landing from the problems it faced, and after 1883 Colville Landing just disappears from view. A rivalry had developed between Selkirk and East Selkirk over which side of the river would dominate shipping and manufacturing. Colville Landing, the East Slough, and East Selkirk were to lose this battle.

The Hudson’s Bay Company was not the only business to operate at Colville Landing. A fishing business operated by Messrs. Reed and Clark was situated on the slough, and several lumbering firms were active there too.

The Manitoba Free Press were reporting activities at the Landing in early 1883. An article dated Jan. 22, 1883 indicated over 50 carloads of lumber and wood were lying in wait at Colville Landing for an engine to take them out. More mention on Feb. 5 and 6 when it stated that an extra train had to be put on at the Rat Portage Division owing to the great quantities of wood and lumber being shipped from Colville Landing. Over 200 cars of freight were unloaded in the CPR yard and it was reported that of these 129 were loaded with wood from Colville and other points East.

As the Selkirk Herald noted on July 27, 1883: “Mr. Banning, of the firm of Dick and Banning, Wpg. paid our town a visit on Saturday last. They are transshipping their lumber for this season at Colville Landing. Mr. F. Dagg, is the agent here, and from thirty to fifty men are employed handling the lumber.

Our good natured friend, Mr. J.M. Neilson, has once more made his appearance amongst us, and has resumed his former duties as agent for Messrs. Brown and Rutherford; to attend to the transshipping and sorting of their lumber at the harbor, 22

The article went on to state that the government dredge was employed dredging the mouth of the south in order to facilitate the entrance of barges and boats arriving daily. Lumber men and others will not find it so difficult hereafter to have their lumber placed exactly where they require it.23

Yet even as these businesses were operating on the slough the death knell of Colville’s Landing was sounding, and of the great aspirations of East Selkirk too. In the spring of 1883 the Northwest Lumbering Company was planning to build a new sawmill in the Selkirk area. For a time, as these references from the James Colcleugh Papers suggest, the mill might have been built on either side of the river, and as Colcleugh knew, wherever it was built it would draw business along with it. On March I l, 1883 James Colcleugh wrote to A.W. Ross, the Member of Parliament for Selkirk that

The Northwest Lumbering (sic) Co., composed of Carmen, Moffat & Calder of Winnipeg and Walkley, Burrows and Bradbury of Selkirk have about decided to build their mill on the East side instead of the West. We made them an offer to locate here which they expressed themselves satisfied with in every respect only that they want an assurance from van Horne that the (sic) road would be complete by the first of July.

As Colcleugh went on to say, however, “… I am inclined to think Carmen prefers building on the East side as his Brick yards are located there. It’s a pity, as if it is a

success it will lead to the establishment of other mills and all the shipping will be down there. “24

One month later Colcleugh and the Selkirk interests had triumphed. On April 10, 1883 Colcleugh wrote to Ross:

We have, after a hard fight, got the Saw Mill located on this side of the river. lt is to be built on Bannatyne’s property by the slough and will be one of the best in the province.25

In this kind of aggressive competition for business the east side of the river regularly lost, and soon the Selkirk Herald was printing stories like this:

Moved Over – Mr. Wm. Gibbs recently purchased a lot from James Colcleugh near the station grounds, and will place on it the building formerly used by him as a shop in East Selkirk.26

East Selkirk tried to attract other businesses as a short article in the Selkirk Herald of March 1, 1885 indicates, but by then it was clear that they were getting desperate. At that time the citizens of East Selkirk offered a $50,000 gift to the “International Mining, Smelting, and Manufacturing Company” which proposed to build a smelter at East Selkirk to refine iron ore from mines on Lake Winnipeg (Black’s Island).27 Nothing came of the proposal, though it is quite possible that East Selkirk lost a lot of money on the deal.

As for Colville Landing the spur line must have been abandoned and taken up by 1883 or 1884 as there is no reference to it in C.P.R. timetable or engineering records.28 The Hudson’s Bay Company would appear to have stopped operating their store and warehouses there at about that time, and it seems that the buildings or at least some of them were sold to Captain William Robinson. Robinson, a flamboyant entrepreneur, was involved in fishing and fish processing, freighting, lumbering and the North West Navigation Company which had shared the facilities of Colville Landing with the Hudson’s Bay Company.29 ln fact the North West Navigation Company was partially owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company.3o

According to Elsie McKay, who wrote extensively on the local history of Selkirk, Robinson used one of the buildings he bought as a store at Colville Landing, and he operated a lumber mill there too. Her source of information would appear to have been William McDonald who at 97 years of age remembered working for Robinson at Colville Landing. Unfortunately there are no references to how long Robinson operated his store at Colville Landing. According to Elsie McKay in 1898 the store was raised on skids, “drawn by a heavy sleigh with a steam-engine for motive power (called a steam-sleigh) and set up on a stone foundation at the north-east corner of Eveline Street and Manitoba Avenue (in Selkirk).”31 She was of the opinion that the store was none other than the barracks-storehouse building from Lower Fort Garry.

Robinson operated a department store in the building until about 1929 when he sold it to william Epstein. Shortly thereafter the building caught fire, and in rather spectacular fashion burned to the ground.32 Thus, while it seems clear that this was the end of the last buildings from Colville Landing, it is impossible to prove whether or not this was the end of the barracks building.

Colville Landing was doomed by two interrelated phenomena: the aggressive promotion of Selkirk by men like James Colcleugh, who helped to appropriate almost all shipping and manufacturing business for “their” slough on the western side of the river, and the westward expansion of the railroad. As the railway moved west it became cheaper and more efficient to ship goods by rail to rail-heads in what became Saskatchewan and Alberta, and then to cart them to Saskatchewan River posts. After 1883 Saskatchewan River steamboat business was concentrated on the Lower Saskatchewan in the environs of the Pas and Cumberland House; it consisted of short haul freight between river posts.33 Colville Landing as a major warehousing and trans-shipment point was rendered obsolete.

The interest of Colville Landing lies in its situation as yet another Manitoba “ghost town” than in its connection with the Hudson’s Bay Company and early railroad and steamboat transportation in Manitoba. Its ties to Lower Fort Garry, a national historic site, and the chance that the mysterious barracks-storehouse building from the fort may have been moved to Colville Landing adds to its appeal. It did not prove to be the great success Brydges and Grahame thought that it would be; it is its failure as a commercial enterprise that gives it a certain allure.

ENDNOTES

A Research paper by Michael Payne, Research Asst.

Historic Researches Branch. April 1981.

1. George Ingram “Industrial and Agricultural Activities at Lower Fort Garry” in Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 4, (Parks Canada: Historic Sites), 1970, pp. 68-69.

2. See Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Molly Basken PaperE box No. 3, Colvile file.

3. Theodore Barris, Fire Canoe (McClelland and Stewart, Toronto), p. 286.

4. Roger Letourneau, “A Brief Resume of the Historical Significance of the Grand Rapids Tramway” (Historic Resources Branch Report) n.d., p. 3.

5. W. Kaye Lamb, History of the Canadian Pacific Railway (Macmillan, New York), p. 49.

6. Lbid., p. 49

7. Hartwell Bows field (ed.), The Letters of Charles John Brydges 1879-1882 (Hudson’s Bay Record Society, Winnipeg), pp. 66-67.

8. lbid., p.69.

9 Hudson’s Bay Company Archives (HBCA) , Al2l49 fo. 264, letters from Grahame to Armit, dated 19th May 1881.

10. See Dominion of Canada, Annual Report of the Minister of Railways and Canals for the Past Fiscal Year From lst July, l88I to 30th June,1882 (Maclean, Roger and Company, Ottawa), 1883. Appendix No. 3. Corporate Archives – Canadian Pacific

11. Bowsfield, op. cit., p9.87.

12 Quoted in Gregory Thomas; “Lower Fort Garry: Period Landscape Study” (Parks Canada), p. 134.

13. lbid., p. 134.

13. lbid., p. 134.

14 Robert Watson, Lower Fort Garry, (Hudson’s Bay Company, Winnipeg), p.54 and George Ingram, “Industrial and Agricultural Activities at Lower Fort Garry”, op. cit., p.83.

15 HBCA, A12l l9 to. 264.

16 lbid., fos.264 and 264d.

17 Manitoba Weekly Free Press and Standard, March 25, 1881, p.5.

18 HBCA; Al2l 19 to. 264d.

19 Bowsfield, op. cit., pp.252-53.

20 HBCA; B265ldl I and 2

21 Selkirk Herald; July 27, 1883 and August 10, 1883.

22 lbid., July 2’7,1883.

23 Ibid

24 Provincial Archives of Manitoba (P.A.M.), James Colcleugh Papers box No. 3, letter No. 466, pp. 500- 01.

25 lbid., letter No. 481, p. 514.

26 Selkirk Herald, January 18, 1884.

27. 1bld., March 1, 1885.

28. Personal correspondence from Omer Lavallee ,Corporate Archivist, Canadian Pacific.

29. Robinson was a fascinating figure in his own right. See Barris, op. cit., pp. 58-64 and passim.

30. lbid., p. 61. 3r Selkirk Enterprise, March 28, 1962 article by Elsie McKay “Robinson’s Department Store – 1899-1929”, part l.

32. Selkirk Enterprise, April 25, 1962, Elsie McKay “Robinson’s Department Store”, part II.

33. Morris Zaslow; The Opening of the Canadian North (McClelland and Stewart, Toronto), p. 56.