Why did Canada build a railway?

There were many reasons for building a transcontinental railway. The primary reason was to unite the forming country of Canada. Territories were becoming provinces, and provinces were joining to form a country. This union was called Confederation. A new government formed as well, and it agreed to build a railway from eastern Canada to the west coast if the people of British Columbia agreed to join Confederation.

Credit: Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) Archives

The railway would cover 3,200 kilometres (2,000 miles) of swamps, bogs, rivers, prairies, and mountains. When the government said the railway would be finished in 10 years, many people believed it was impossible to do.

The new government wanted to fill the country with settlers and immigrants, and anticipated that the railway would bring them to the region. It would also offer a faster, more direct route for long distant travel and a less problematic way to ship freight. The government named the new railway the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) and over the years, that railway would provide dividends to the overall development of Canada.

Credit: Canadian Pacific Railway Archives

A LITTLE BACKGROUD ABOUT CONFEDERATION

Before Confederation

Before 1867, there was no Canada; only open, unbound land lived on by First Nations peoples and a few colonies built by British North American immigrants. European explorers, most especially from the countries of Britain (England) and France, sailed to North America throughout the 1500s and 1600s to claim land and build colonies. The first colonies included Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Lower Canada (Quebec), Upper Canada (Ontario), and British Columbia.

The name given to the land between the eastern colonies and British Columbia was Rupert’s Land. King Charles II of England named it when he established the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1670 and claimed all the land that drained into Hudson Bay, from modern day Alberta to Quebec and from Hudson Bay south to the northern United States. This huge parcel of land covered about forty percent of modern day Canada. The Hudson’s Bay Company was the only form of government within the territory before Confederation outside First Nations communities. The land was home to First Nations people. King Charles II claimed this land without their consent.

Origin of the Name – Canada

The meaning of the word Canada or Kanata is village or settlement. It dates to about 1535 when explorer Jacques Cartier noted that two First Nations guides from the Huron-Iroquois Nation told him the way to “Kanata.” They referred to the village of Stadacona (modern day Quebec City). The first official spelling Canada was noted in 1791 when the province of Quebec divided into two colonies called Upper and Lower Canada. At the time of Confederation, the new country assumed the name.

All First Nations peoples had their own name for the country we now call Canada, spoken in their own languages. An English translation that best represents that name is TurtleIsland because it resembles the shell of a turtle surrounded by oceans.

Confederation

By the early 1860s, the colonies wanted to unite to form the country of Canada. This involved the work and discussion of many men, but one man in particular stands out in Canadian history. His name was John A. Macdonald. He was a member of the Conservative (Tory) Party and worked to unite English and French politicians and bring together the unification of colonies. The Government planned a series of conferences to discuss the union and draft the British North American Act (BNA Act).

The BNA Act is the base document for the Canadian Constitution.

- It set up the rules for the government

- Formed a British style parliament with a House of Commons and a Senate

- Established a division of power between the federal and provincial governments

At a conference, held in London England in 1867, Queen Victoria signed the BNA Act uniting four colonies into provinces. They were Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, and Ontario. On 1 July 1867, the British North American Act (BNA) passed, creating the Dominion of Canada.

With the exception of Queen Victoria, only men were involved in creating the BNA Act. First Nations peoples were excluded from negotiations, even though their ancestors had lived on the land for many generations. Women were excluded too, and therefore, they, like First Nations peoples, had no say about the future of their country.

It would take 100 years to add the other six provinces and three territories that make up Canada today. Manitoba and the North West Territories joined in 1870. British Columbia joined the following year, 1871.

Queen Victoria

WHO BUILT THE RAILWAY?

Many people worked to build the Canadian Pacific Railway. However, a few people played significant roles. Let’s meet them

John A. Macdonald – Canada’s first Prime Minister:

John A. Macdonald and his Conservative (Tory) Party were in political power at the time of Confederation. They made the decision to build the new railway.

Born:

- January 10 or 11, 1815 – Glasgow, Scotland

- Parents: Helen (Shaw) and Hugh Macdonald

- Immigrated to North America (eastern Canada) 1820

- Family settled in Kingston, Ontario

Education:

- Midland District Grammar School and John Cruikshank School, Kingston (Ontario)

Personal Life:

- 1st wife: Isabella Clark, 1843

- Two sons, John (died in infancy), Hugh John.

- 2nd wife: Susan Agnes Bernard, 1867

- One daughter, Margaret

Occupations:

- Lawyer

- Businessman

- Alderman

- Prime Minister

- Knighted by Queen Victoria for his role in Confederation

Death:

– 6 June 1891, Ottawa (Ontario)

– Gravesite: Cataraqui Cemetery, near Kingston (Ontario)

Sandford Fleming – The Surveyor:

Sandford Fleming was one of the surveyors for the railway project. He was also its chief engineer responsible for its design.

Born:

- January 7, 1827, Kirkcaldy, Scotland

- Parents: Elizabeth Arnot and Andrew Fleming

- Immigrated to Upper Canada in 1819

Personal Life:

- Married Anne Jane (Jean) Hall, 1855

- Fathered five sons, and four daughters

Occupation:

- Surveyor

- Engineer

- Draftsman

- Mapmaker

- Assistant Engineer of the Ontario, Simcoe, Huron Union Railroad

- Presented the first well thought out plan for the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway to the Canadian Government, based on iron construction, stone bridges, and soil sampling.

- Presented the plan of laying rails to Winnipeg (then called Red River Settlement) to the Canadian Government and the British Imperial Government.

- Key figure in engineering the design of the railway, especially in the construction of bridges. He favoured stone and iron construction while other engineers preferred to use timber.

- 1871, became Chief Engineer of the Canadian Pacific Railway

Death:

- July 22, 1915

- Buried at Beechwood Cemetery, Ottawa

Finding a Western Route for the Railway

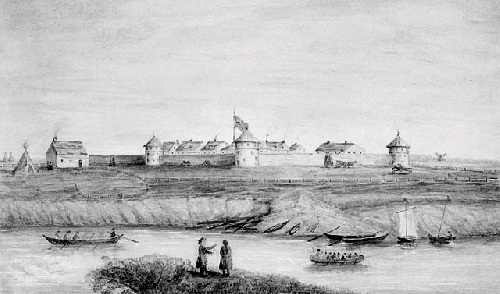

To ensure the best possible route to Winnipeg, Sandford Fleming divided the country into three sections and sent men out to survey each section. Fleming and a small group of men headed west travelling by steamer, canoe, wagon, and horseback. Fleming’s 16-year-old son, Frank, accompanied them as did Rev. George Grant, minister of Fleming’s church in Halifax who served as secretary. Grant wrote a colourful description of their travels that he later published called, Ocean to Ocean (1873). The Fleming party arrived at Fort Garry (Winnipeg) on 2 August 1872. Rev. Grant wrote:

At 3 P.M., we reached the Red River, which flows northward, at a point below its junction with the Assiniboine, and crossed in a scow; drove across the tongue of land, formed by it and the Assiniboine coming from the west, into the village of Winnipeg, and from there to the Fort, where the Government House is at present.

James Lockhart watercolour, HBC Upper Fort Garry, Red River Settlement, 1868

Library and Archives Canada

By 1877, surveyors had covered more than 19,000 kilometres (12,000 miles) of countryside.

- Surveyors searched out the flattest ground in the shortest route.

- They used long survey chains to divide the route into 30 metre (100 ft) lengths.

- They used an instrument called a transit to measure the angles between landmarks. It helped to calculate distance.

Sandford Fleming recommended a bridge at Selkirk:

Sanford Fleming suggested the Canadian Pacific Railway mainline west of Lake Superior take a northwesterly course from Fort William (Thunder Bay) to Manitoba. In his opinion, it would be best to build a bridge for the mainline to cross Red River near Selkirk because its high riverbanks would provide protection for the bridge from destructive floodwaters. From there, the rail line would proceed north between lakes Winnipeg and Manitoba across the narrows to Edmonton. In the words of Sanford Fleming:

Wherever the railway forms a convenient connection with the deep water of the river, that point will practically become the head of navigation of Lake Winnipeg. In course of time, a busy town will spring up and the land of the town site will assume a value it never before possessed. To the north of Sugar Point, in the locality designated Selkirk, a block of more than 1,000 acres remains ungranted and under the control of the Government – this is probably the only block of land along the whole course of the Red River which has not passed into private hands or into the possession of the Hudson Bay Co.

This large block of land abuts the river, where a bridge may be constructed with least apprehension as to the safety of the structure in time of flood, and where its erection could, under no circumstances, involved questions of damages. Near the river there is a natural deep water inlet, which can easily be reached by a short branch from the main line of the railway; along this inlet, and between it and the river, the land is admirably suited for a capacious piling ground, vessels lying in the inlet are in no way exposed to damage from floods, in proof of which it may be mentioned that the Hudson Bay Co., have used it as a place of shelter for years past.

The Pacific Scandal

In 1873, one year after the Fleming survey crew surveyed the lands for the railway, scandal broke out with the Canadian government. Accusations arose that certain members of the Macdonald party accepted bribes from private financiers that resulted in those individuals receiving railway contracts. Known as The Pacific Scandal, John A. Macdonald and his Conservative (Tory) Party lost political power in 1873 because of it. The newly elected Prime Minister, Alexander Mackenzie, and his Liberal party, believed the railway should proceed only as quickly as government funds allowed, creating a slower pace for construction between 1873 and 1878. Railway workers laid about 76 miles of rail outside Fort William (Thunder Bay) and east of Selkirk during that time.

The Roundhouse or Engine-house at East Selkirk:

By 1875-76, industry grew in the regions of east and west Selkirk, and white immigrant population soared as news travelled that a transcontinental railway was coming west. Surveyors began to map out the town site. On Sandford Fleming’s recommendation, the main town site was to be on the east side of Red River. The Canadian government developed plans to build a Roundhouse/Engine-house there to repair and maintain the Canadian Pacific Railway locomotives. The construction site lay near Red River on modern day Frank Street, East Selkirk. Construction of the building began in 1878.

- It was a large building at 90 ft. by 180 ft. with a large turntable for moving engines during repair.

- Its foundation was two ft. thick and twelve ft. deep.

- The strength of the building came from its building material – tyndal stone and brick.

- It had high ceilings; about 15 ft. in most places except in the middle where it reached 30 ft. with steel beams to lift heavy equipment.

- The main building had four wings, also made of brick.

- The building was equipped with large windows that opened with pulleys and had good ventilation for engine smoke.

- It had a 50-ft. square basement made of stone with a brick floor and ten smaller cellars about 4 ft. wide, 5 ft. deep, and 20 ft. long, walled and floored with bricks.

- An impressive building, that cost about $60,000.00 to build. Construction moved along quickly. The building was officially complete by January 1880.

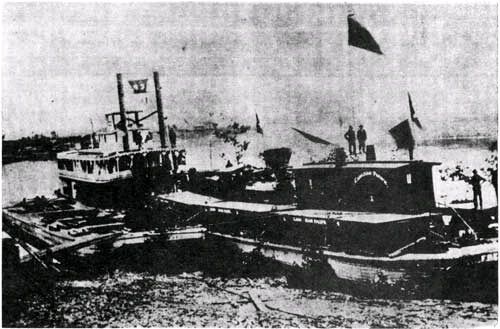

At about this same time railway workers built a short railway line from the East Selkirk town site to the head of the east slough on Red River at the mouth of Joe Cooks Creek. This was called a spur line. Spur lines were railway lines that linked to main lines. They built this line so trains could travel to the Hudson’s Bay Company shipping wharf and warehouse called Colvile Landing. Boats docked at Colvile Landing wharf to transfer freight and passengers to and from the train. One of the steamers, The Colville carried goods and passengers to communities on Lake Winnipeg for more than 20 years until fire destroyed it in 1894 at Grand Rapids, Manitoba.

The Countess of Dufferin, Manitoba’s first locomotive

The first locomotive to arrive in Manitoba was the Countess of Dufferin. The locomotive, along with six flat cars, a caboose, and construction material were loaded onto barges at Fisher’s Landing, Minnesota (USA) and transported up the Red River by the SS Selkirk. It arrived in St. Boniface on 8 October 1877. Built by Baldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia, USA in 1872 and named after Hariot Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, the wife of the Earl of Dufferin and the then Governor General of Canada, the Countess of Dufferin was the first steam engine on the prairies. Railway workers used her to construct a line from St. Boniface, Manitoba(Canada) south to St. Paul, Minnesota (USA). The last spike was driven at Dominion City, Manitoba when the Countess of Dufferin met contractors from the USA linking the two countries together. The Countess of Dufferin currently sits on display in the Winnipeg Railway Museum, Winnipeg.

- The Countess of Dufferin, and early engines of her time, was called a locomotive.

- Early locomotives were powered by steam.

- Steam was made from coal or wood and water.

- Steam locomotives used lots of water and so a train pulled a special rail car called a tender or a coal car to carry the coal, wood and water.

- Workers called fireman shoveled the coal or wood into the fire in the engine to heat the water.

- The boiling water produced steam.

- The steam pushed the train’s pistons back and forth, which moved the driving rods, which turned the large driving wheels that moved the train along the tracks.

The Countess of Dufferin had a smokestack at the front of the engine to blow smoke high about her, preventing sparks to ignite grass fires and from damaging passenger’s hats. Early trains had whistles to warn people and animals that the train was coming. They also had a headlight that helped the engineer to see anything on the rack at night.

The Countess of Dufferin also had a cowcatcher. It is a cluster of metal bars at the front of the train more officially known as “the pilot.” The bars prevent objects on the track from hitting the train and derailing it from the track. Agnes Macdonald, wife of Prime Minister Macdonald sat on the cowcatcher for most of their trip through the mountains. She said this about it: “So steady was the engine that I felt perfectly secure and the only damage we did from Ottawa to the sea was to kill a lovely little fat pig.”

Passenger trains had different train cars:

- Colonist car – most basic type with hard wooden benches and uncomfortable platforms called berths where people slept. Passengers had to supply their own blankets and bring along their own meals. Settlers used colonist cars. There were no washrooms on trains, so people had to wait until the trains stopped at a railway station to use the washroom.

- Coach car – was used for short trips. Passengers could buy sandwiches, candy, coffee, cold drinks, and newspapers and rent pillows for sleeping.

- Sleeping car – Passengers making a long journey could rent a sleeping car. Seats were turned into beds and pulled down from overhead. Colonist Car – CPR Archives

- Dining car – Dining cars were usually used by rich people. They were set with fine china, silverware, and linen tablecloths. A professional chef made gourmet meals that male waiters served to the passengers.

- Private car – These cars were lush with wood walls, stained-glass window and carpet. They had bathrooms, along with hot and cold water. Men such as William Van Horn, President of the CPR had private cars.

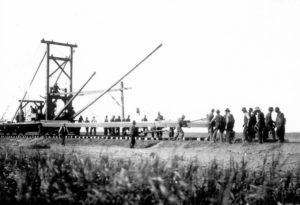

HOW THE RAILWAY WAS BUILT

Building the railway was hard work. First, surveyors like Sandford Fleming surveyed the land to find the best possible route over swamps, bogs, waterways, and finally the Rocky Mountains. The government hired people as managers and labourers to do the physical work.

– Men called Navvies cleared the trees and brush from the railway route.

– Grading crews graded and elevated the roadbed using teams of horses pulling  scrapers and plows.

scrapers and plows.

– Tracklayers laid wooden railway ties across the roadbed 61 centimetres (2 ft) apart using local trees.

– Steel rails 12 metres (39 ft) were laid on each side of the ties and iron spikes were hammered in to hold the rails in place.

– Gravel was spread between the ties for stability.

– Bridge crews built bridges and trestles.

– Dynamite blasters worked in mountainous terrain to blast through the rock.

Telegraph Line

After the tracklayers laid the track, another crew set up poles and strung telegraph wires along the tracks. The telegraph was similar to our modern day telephone. It brought news from afar and enabled people to be in touch with each other from far away.

How it worked

- Electricity – electric current started when turned on (like a modern day light switch).

- Electric current ran through the telegraph lines that ran along the railway track.

- The switch to turn on a telegraph device was called a Morse Key.

- When the operator pushed on the key, electricity flowed through the device. When the operator released the key, electricity stopped.

- In early times, telegraph offices used batteries to power the device because electrical power was not yet readily available.

- Telegraph operators used Morse Code to send messages.

- Morse Code was made up of dots and dashes – the dots stood for short bursts of electricity sent along the wires, the dashes stood for long bursts of electricity representing letters and numbers.

- Samuel F. B. Morse invented Morse Code.

The CPR mainline crossed at Winnipeg

In the spring of 1880, the Canadian government made plans on the recommendation of Sandford Fleming, Chief Engineer of the Canadian Pacific Railway to build a railway bridge to cross Red River at Selkirk.

Winnipeg and St. Boniface were the larger centers with the greater population, resources, and industry along with economical and political strength. Residents disagreed with the government’s decision to cross Red River at Selkirk. They believed Winnipeg was the better choice. They formed committees and asked the City of Winnipeg Council to present their argument for a Winnipeg crossing to the federal government.

Sanford Fleming argued to the Minister of Railways that Winnipeg was too prone to flooding with its low riverbanks. Discussions went on for some time. Railway officials asked the people of Selkirk to raise $125,000.00 for a bridge at Selkirk and to construct rails west of Selkirk. Selkirk was unable to raise the funds.

After years of negotiations, the Canadian Pacific Railway decided to cross Red River at Winnipeg. The city of Winnipeg agreed to:

– Pay a $200,000.00 bonus to the CPR to aid in the construction of the line.

– Offer the CPR a free right of way worth about $20.000.00

– Build a bridge over Red River at a cost of $250,000.00 (the Louise Bridge)

– In return, the CPR guaranteed the city a position on the main line, as well as maintenance shops for its western operations.

After the railway-line went south to Winnipeg, much of the business and population of East Selkirk followed it. East Selkirk became a bit of a ghost town.

The Canadian Pacific Railway incorporated

The Governor General of Canada, Sir John Douglas Campbell (the Marquess of Lorne), declared the Canadian Pacific Railway an “official” railway after it was given royal assent on 15 February 1881. It incorporated the following day, 16 February 1881. The government gave the newly formed company twenty-five million dollars and twenty-five million acres to build their transcontinental railway.

Sir William Cornelius Van Horne:

“Nothing is too small to know, and nothing is too big to attempt.”

The Canadian Pacific Railway hired American born William C. Van Horne to manage the building of a railway from Fort William (Thunder Bay) to Winnipeg and west across the prairies, through, and across the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia.

Railway tycoon James Hill wrote of Van Horne, “I have never met anyone who is better informed in the various departments: Machinery, Cars, Operations, Train Service, Construction and general policy which with untiring energy and a good vigorous body should give us good results.”

The Company offered Van Horne a huge salary at 15,000.00 – the highest salary paid to a railway manager. He arrived in Winnipeg on 31 December 1881. On 2 January 1882, he became general manager of the CPR.

Born:

- February 3, 1843 Will County, Illinois (USA)

- Parents: Mary Minier Richards and Cornelius Covenhoven Van Horne

The first of five children, William’s mother schooled the children until the family moved to Joilet, Illinois where there was a school. William was about eight years old. He loved to draw at a very young age and he was a keen reader of books. His mother encouraged him to draw and read everyday.

William was eleven when his father, a lawyer and farmer, suddenly died of cholera in 1854. William took a job to help support his family by carrying telegraph messages for a nearby railway office. He learned to send and receive Morse Code. Other people said he could, “decode telegraphic messages by simply listening to the clicks rather than recording and reading them.” He did all kinds of jobs for the railway and learned everything he could about how it worked.

As a grandfather, Van Horne wrote a letter to his beloved grandson, William, telling him of an event in his young life that inspired him to become what he became. He said he watched in awe one day when the General Superintendent of Michigan Central Railway arrived in his private railway car, dressed in fine clothes. Van Horne peered into the car to see, “the luxurious easy chairs and dinning room table covered with gleaming white linen and decorated with flowers.”. Van Horne was captivated. His told his grandson: “I found myself wondering if even I might not somehow become a General Superintendent and travel in a private car. The glories of it, the pride of it, the salary pertaining to it, and all that moved me deeply, and I made up my mind then and there that I would reach it.”

Marriage:

- Lucy Adeline Hurd of Galesburg, Illinois in 1867

- Three children, two sons (one died in infancy), one daughter

Interests:

- geology

- gardening

- farming

- art collecting

- sketching

- He drew elephants on trains. He made postcards and drew elephants and trains on them – “Trunks all Aboard,” he wrote. Authors have written books with this title.

Others described William Van Horne as a tall and muscularly built man with a brilliant mind, remarkable drive, endless energy, and a forceful personality that at times made him ruthless and authoritarian in his leadership. By 1881, he was well known and well respected for his work in the railway business and that was why the CPR hired him to become their general manager.

When Van Horne arrived in Winnipeg in 1881, it was a very different place than it is today. Newspaper reporter George M. Grant, from The Globe, wrote, “I suppose that no city in Canada has had so rapid a growth as Winnipeg up to the point attained by it so far, and probably in the infancy of no city on the continent have town lots commanded such prices as those that are now readily paid here.” With the CPR’s decision to build its main line through Winnipeg, the population and land prices increased rapidly.

Van Horne set to work immediately to hire workers to connect the CPR line from Winnipeg to Fort William (Thunder Bay) and westward toward the Rocky Mountains. The first summer the CPR reached a distance of just under 800 kilometres (500) miles. The job included 5000 men and 1700 teams of horses.

Van Horne work tirelessly to complete the task he had accepted. He encountered untrustworthy staff, strikes, and financial troubles of the CPR, land issues, severe weather conditions, and time restraints to name a few issues. He let none of it stop him.

Positions with the CPR:

- 1882 – General Manager

- 1884 – Vice President

- 1888 to 1899 – President

- 1899 – retired at the age of 56 due to ill health

- 1899 to 1910 – Chairman of the Board

- The Canadian Railway Hall of Fame memorialized his valuable and long lasting contributions.

Canadian homes:

- A mansion on Sherbrooke Street West, Montreal

- An estate on Minister’s Island, New Brunswick called Covenhoven, named after his father.

- A 3,000-acre farm in East Selkirk where pedigree cattle were bred, crops were planted and harvested, livestock and farming fairs were held, and employment was created for many people began. The farm expanded over the years of its operation. It was sold in the 1930s.

Van Horne died on 11 September 1915 in Montreal. He was 73 years old. His wife and children returned his body to Joliet, Illinois (USA) on a special CPR train for burial. Among his many contributions, people remember him best for the construction of the promised rail link that brought British Columbia into Confederation.

The Fate of the East Selkirk Roundhouse (Enginehouse)

Although the Canadian government built the East Selkirk Roundhouse to repair locomotive engines, the building never really served that purpose after the CPR mainline went south to Winnipeg. However, it did serve as a:

- Dance hall

- Recreation centre

- School

- Hospital

- Church

- General meeting place

- Immigration shed

Between 1880 and 1900, thousands of people from eastern and central Europe immigrated to eastern Canada hoping to find a better life for themselves and their families. The Canadian government wanted to increase the population in western Canada, so they sent thousands of those new immigrants westward by train. After arriving in Winnipeg, they travelled to East Selkirk and lodged temporarily in the Roundhouse. These immigrants came from the counties of Russia, Poland, Germany, Austria, Hungry, Latvia, and Ukraine – especially from the provinces of Galicia and Bukovina, Ukraine.

These families applied for land through the Homestead Act. Men sought work in logging, on the railway, and in mining. Women worked on their homesteads caring for children, livestock, fields, and gardens. Many families in the East Selkirk area became vegetable farmers.

By 1906, the Roundhouse was in need of major repair after the government stopped using it for immigration purposes. Between the years of 1906 to 1916, it functioned as a summer dance hall and a winter skating rink. In 1916, demolition crews began to dissolve it – some of its stone found a new home in the construction of Happy Thought School in East Selkirk.

The Canadian Pacific Railway reached goal

As the year of 1885 neared its end, so did the laying of rails. William Van Horne had succeeded in pushing 2,400 miles of railway across Canada in less time then predicted. William Van Horne boarded the Saskatchewanin Montreal with his eight-year old son, Bennie in late October to witness the last spike entering the ground in British Columbia. In another private car, rode Donald Smith, Lord Strathcona. Sandford Fleming boarded at Ottawa. In Winnipeg, John McTavish, land commissioner, George Harris, A Boston financier and CPR director, and J.J. C. Abbott, the company lawyer all boarded. A second train followed carrying a second group of company officials. The trains reached Eagle Pass, to the chosen spot where the last spike would connect east and western Canada. The regional rock reminded Donald Smith of the rock in Banffshire, Scotland called, Craigellachie. Therefore, the commemorative spot came to be, Craigellachie. Donald A. Smith drove the last rail spike into the ground on 7 November 1885.

The group called William Van Horne to make a speech about the completion of the railway. Never comfortable with public speaking, Van Horne is noted as saying this brief comment,” All I can say is that the work has been well done in every way.

DID YOU KNOW?

- In 1862, Sandford Fleming, surveyor of the railroad and the man who made standard time, suggested the railway be built across Canada.

- Before the nineteenth century, every town had its own time. CPR engineer, Sandford Fleming divided the world into 24 time zones so all clocks in each time zone were set to the same time. This helped people board their trains on time.

- Building the railway was dangerous work, many men were injured and some were killed by work related accidents.

- Confederation officially began in 1867. Canada became a country.

- The name Canada or Kanata means village or settlement. It is a word from the Huron-Iroquoian First Nation.

- John A. Macdonald was Canada’s first Prime Minister.

- Roads in early Canada were only pathways and the waterways, which many people used to travel on, were frozen for up to 5 months each year. The railway provided a better, faster way to travel.

- Telegraph lines were built alongside railway tracks.

- The large steel wheels attached to the engine were the driving wheels. They made the train move.

- The Countess of Dufferin arrived in St. Boniface, Manitoba on 8 October 1877.

- The CPR Roundhouse at East Selkirk was used as an Immigration Shed.

- The last spike to connect the rails between Manitoba Canada and Minnesota, USA was driven at Dominion City, Manitoba.

- Railway management and workers held their own ceremony to celebrate the completion of the railway called, The Last Spike Ceremony.

- A silver spike was made for the Last Spike ceremony, but they used a plain iron spike instead.

- The last spike was driven at Craigellachie, British Columbia on November 7, 1885. The promised rail link that brought British Columbia into Confederation was officially complete. However, there were still parts of the railroad unfinished.

Glossary

Bridge crews – men who built train bridges and trestles

British North American Act (BNA) – The BNA Act is the base document for the Canadian Constitution

Cabose – the last train car

CPR – Canadian Pacific Railway

Conductor – the boss or captain of the train

Confederation – a union or alliance of provinces or states

Conservative Party – a political party promoting free enterprise and private ownership

Cowcatcher: a piece of steel on the front of the train used to move objects and animals off the track

Dynamite Crew – men who used dynamite to blast rock to make way for the train track

Engineer – drives the train

Grading crews – men who cleared the trees from the railway route

Immigrants – people who moved to a new country

King Charles – King of England (1630-1685) reigned over England, Scotland, and Ireland from 1660-1685

Locomotive – train engine

Morse Code – a system of dots and dashes used to send messages by telegraph

Morse Key – part of telegraph device that is raised or lowered to stop or start flow of electric current

Navvies – men who built roadbed

Queen Victoria – Queen of England (1819-1901) was the Queen of England and Ireland from 1837 until her death in 1901.

Prime Minister – head of an elected government

Red River Settlement – precursor of Winnipeg

Roadbed – the foundation or base that a railway is built on

Rupert’s Land – the name given to most of western Canada by King Charles II in 1670

Spur line – a railway line connected to a trunk line, or the main route

Surveyor – a person who surveys land and buildings

Telegraph – a form of communication by sending electric impulses through wires over far distance

Telegrapher – a person who operates a telegraph

Tender – a coal car that was pulled behind the engine with coal, wood and water to power the engine

Ties – the wooden beams of railway tracked that the rails sit on

Tracklayers – laid railway track using ion spikes to fasten wooden ties

Trestles – a framework that holds up a railway bridge

Sources Used

Creet, Mario Sir Sandford Fleming, Dictionary of Canadian Biography on-line at Library and Archives Canada: http://www.biographi.ca

Grant, George M., Ocean to Ocean: Sandford Fleming’s Expedition Through Canada in 1872 (Toronto: Prospero Books, 2000)

Hodge, Deborah, (Illustrator John Mantha) The Kids Book of Canada’s RAILWAY and How the CPR was Built, (Toronto: Kids Can Press, 2000)

Hossell, Karen Price Morse Code (Chicago: Heinemann Library, 2003)

Knowles, Valerie, From Telegrapher to Titan: The Life of William C. Van Horne. (Toronto: The Dundrun Group, 2004)

Mercredi Ovide & Turpel, Mary, In the Rapids: Navigating the Future of First Nations (Toronto: Viking, 1993)

Potyondi, Barry Selkirk, The First Hundred Years (Winnipeg, 1981)

St. Clements Heritage, East Sideof the Red 1884-1984 (RM St. Clements, 1984)

Watson, Galadriel, The Railway (Calgary: Weigl Educational Publishers, 2005)

Wishinsky, Frieda (Illustrator Leanne Franson) All Aboard! (Toronto: Maple Tree Press, 2008)

Websites Used

Confederation for Kids at Library and Archives Canada at:

http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/confederation/kids/index-e.html

Countess of Dufferin, WinnipegRailway Museumwebsite at: http://www.wpgrailwaymuseum.com/loco-countess.html

Local and Provincial Items, Manitoban and Northwest Herald Newspaper, 3 August 1872, On-line at: www.Manitobica.ca

“People” Confederation for Kids at Library and Archives Canada On-line at:

http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/confederation/kids/023002-3000-e.html

Origin of the Name – Canada Canadian Heritage at: http://www.pch.gc.ca/pgm/ceem-cced/symbl/o5-eng.cfm

Sir Sandford Fleming – Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Library and Archives Canada at:

http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?BioId=41492

Sir Sandford Fleming – Wikipedia at:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sandford_Fleming

Article Credit

Researched and written by Donna G. Sutherland, Historian