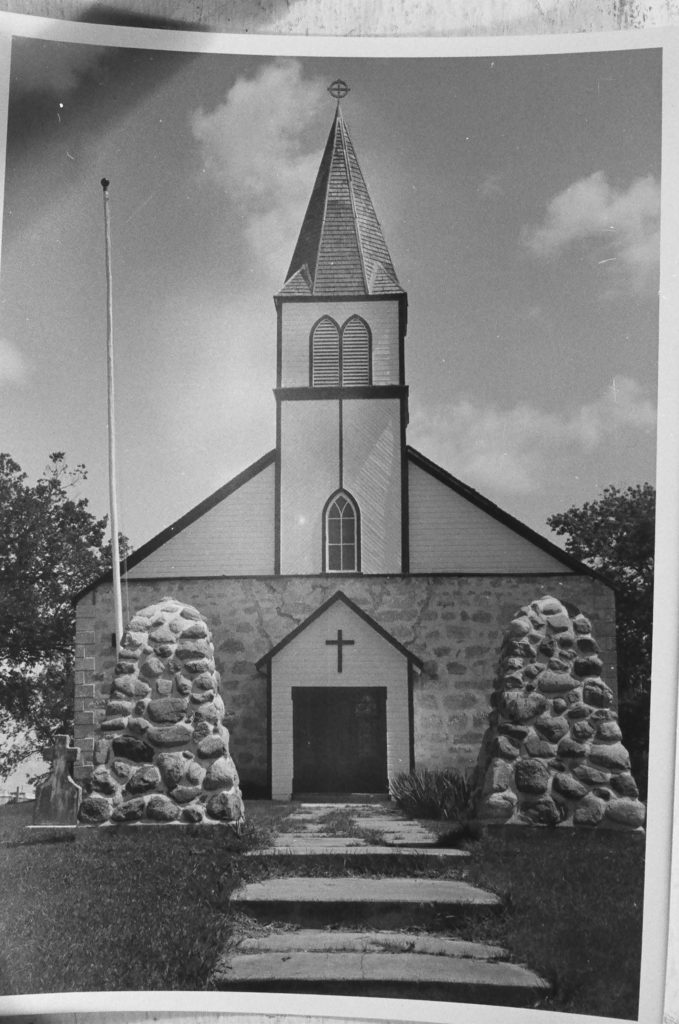

St. Peter’s Church, Dynevor, one of the oldest stone churches on the prairies, stands three miles north of East Selkirk at the mouth of Cook’s Creek. The site of the oldest Indian mission in Western Canada, the church was the only Indian church among the seventeen parishes of the Red River Settlement. The Reverend William Cockran, who contributed more to Anglican missionary work in Red River than any other individual, was the driving force behind St. Peter’s Church and the surrounding Indian agricultural settlement which was the first of its kind in Western Canada.

William Cockran came to Red River with his wife on 14 October 1825 to serve as an assistant to the Reverend David Jones at the Middle and Upper Churches (St. Paul’s and St. John’s). When Jones left in 1829 for a year’s furlough in England, Cockran moved down to the Lower Church at Grand Rapids, now called St. Andrew’s. While there, his attention was caught by the bands of Swampy Cree and Saulteaux Indians who customarily gathered at Netley Creek eleven miles down river. For some years prior to this the Indians had visited Red River, begging for food to replace the game whose habitat had been destroyed to make way for agriculture. It was clear they needed assistance but it was not until Cockran arrived that any organized program was undertaken. Hoping to evangelize them as well as improve their material condition, the Reverend Cockran began encouraging the Indians to pursue an agricultural existence. It was felt that Indians who were supporting themselves by cultivating the land were easier to convert and that religious instruction had relatively little effect until they were so settled.

At first the Indians resisted the idea, for they could see no advantage to the business of farming. Floods, droughts and grasshoppers were commonplace, and offered little incentive to people who were unused to this way of life. As well, the Hudson’s Bay Company, whose interest lay in the fur trade, was not in favour of any endeavour which turned the Indians away from trapping and hunting. Nevertheless, in October 1831 Cockran received Governor Simpson’s reluctant consent to start an experimental farm at Netley Creek.

By 1832 Chief Peguis, leader of the Saulteaux, and a few Indian families had been persuaded to attempt the experiment. Peguis, sixty years old at the time and having just endured a severe winter in which many of his band had come close to starvation, was attracted by Cockran’s promises that farming would provide comfort and prosperity. Also, the Indians had witnessed the gains that were possible through farming, by their close association with the Selkirk settlers. Thus in 1832 the first attempt at an Indian agricultural settlement was made at Sugar Point above the town of Selkirk. The site had been chosen because of the Indians’ attachment to the area but the land proved too low and swampy. After the first year, which saw limited returns, the project moved three to four miles down river to a spot near Cook’s Creek.

In this new location the seven original farmers were joined by another seven and in subsequent years the settlement grew steadily. In 1834 a log schoolhouse was constructed; the 20 foot by 40 foot building also functioned as a teacher’s residence and had a loft which doubled as a granary. Joseph Cook, son of Chief Factor William Cook of York Factory, became the settlement’s first teacher and when the school was opened on I I July thirty-two children were in attendance. Log houses were built on small river lots and a number of cattle were acquired. In 1835 a windmill was built — an important source of motivation as it allowed the Indians to see the results of their labour being turned into flour. Encouraged by these advances, Cockran decided that it was time for a church to be constructed. In 1836 work was begun on a 54 foot by 24 foot building capable of holding 300 people, and it was officially opened on 4 January 1837. This first church on the site of St’ Peter’s was described by Bishop Mountain on his visit in 1844 as “a wooden building, painted white … with a cupola over the entrance and square-topped windows. “

In 1838 the population of the Indian settlement numbered 239, although the number who had devoted themselves to farming was smaller and only 5 1/2 acres were under cultivation. ‘Two years later this figure had increased to a promising 86 1/2 acres and by 1849 the population of 460 was cultivating 230 acres. Still, in the early years Cockran found the struggle for Christian converts and the transition to an agricultural lifestyle difficult, for many of the Indians were reluctant to relinquish their traditional beliefs and practices. As farmers, they often harvested their crops and gave them away to their less fortunate brothers in the traditional manner instead of putting by a store for winter. Cockran found the Indians relying on him when supplies were scarce. He also found it necessary to feed the children who attended school and was forced to give them food to take home to help convince their parents to allow them to attend.

When the Reverend Jones departed for England in 1838 Cockran’s responsibilities increased and he began to find the long hours a strain. Chief Peguis, as leader of the native community, sent a moving appeal for another clergyman to the Church Missionary Society: “When we heard the Word of God we did not altogether like it; for it told us to leave off getting drunk, to leave off adultery, and to keep only one wife and to cast away our rattles, drums and our gods, and all our bad heathen ways; … Mr. Jones is now going to leave us. Mr. Cockran’s talking of leaving us. Must we turn to our idols and gods again? Surely then our friends’ 300 souls is worthy of one praying master.

In September 1839 the petition was answered by the Reverend John Smithurst, who arrived at Red River to take over Cockran’s work in the Indian settlement. The latter was stationed at the Upper Church, in St. Cross house, without specific duties in order to recuperate.

An experienced agriculturalist, Smithurst practiced the role of the clergyman-farmer and the settlement thrived under his guidance. The evangelization of the Indians proceeded rapidly. In his report for 1842 Smithurst stated that the Sunday morning service drew a congregation of 250 when the prayers were in the Indian language, the Sunday School had 184 scholars and a large group attended evening lectures from Monday to Friday. When Bishop George Jehosaphet Mountain came west from Montreal in 1844 to inspect the work being done in Rupert’s Land, Smithurst was able to present 204 candidates for confirmation.

In time, however, this strenuous labour also took its toll on Smithurst. While the settlement continued to grow many of its members preserved their loyalties to their traditional way of life and tended to drift away. His original enthusiasm dampened, Smithurst returned to England in the summer of 1851

Cockran, his energy renewed, was now eager to resume his work at Red River. With Smithurst’s departure he returned, this time to live in the settlement instead of commuting from St. Andrew’s as he had done in his previous tenure. Finding the church of 1836 worn with age and too small for the settlement, whose population was now close to 500, Cockran immediately proposed to the Church Missionary Society that a new stone edifice be constructed.

The C.M.S. held Cockran in high regard and was willing to grant his request. Local monies were raised through subscription and was donated by Bishop Anderson of the new Diocese of Rupert’s Land. The Indians of the settlement were to provide much of the labour. In the fall of 1852 eighty cords of stone were being quarried. This kept the stonemasons (one of whom was the well-known Red River mason, Duncan McRae) busy all winter dressing stone for the corners, windows and doors. By May a foundation 4 feet deep and 3 I 12 feet thick was laid and on 23 May 1853 Bishop Anderson placed the cornerstone and assigned the church the name of St. Peter. This was just eight years after the cornerstone of St. Andrew’s Church had been laid.

St. Peter’s foundation was 70 feet long and 40 feet wide. The walls were erected using block and tackle and some stout boards, and mortar was made by burning lime in a kiln. Glass for the windows was shipped from Britain by placing it in barrels of hot, thick molasses which was allowed to harden before shipping. On arrival the molasses was heated and removed. To complete all of this before winter it was necessary to work very long hours. From 5 a.m. to 7 p.m. Cockran worked alongside the Native people who, unused to such long, steady labour, needed constant supervision and encouragement. At the end of July, shortly after 24 foot long rafters were floated down the river, work nearly came to a halt as funds, provisions, masons and enthusiasm all became scarce.

The church was roofed but not finished when winter came, but was ready for use the following year. Though dedicated at this time, St. Peter’s was not consecrated until 18 June 1886, when the debts incurred in its construction were written off.

Cockran’s second term as incumbent of St. Peter’s saw a renewal of the life of the church and its mission. In 1857, the groundwork having been laid, he left to start a new mission at Portage la Prairie. Cockran’s successor’ the Reverend Abraham Cowley, had come to the settlement some years earlier and had helped to build the church and continue the evangelization of the Indians’ However, after 1857 this missionary work gradually diminished as the make-up of the settlement changed’ Tensions between the Saulteaux and Cree and between Christian and Non-Christian Indians after Chief Peguis’ death in 1865 caused divisions within the settlement’ Also, the influx of Canadian settlers to Red River in the 1860s and 1870s forced a contraction of the parish’s rich farmlands. Indian farmers were bought out by new settlers and as the white and Metis presence increased the native population dispersed. The area was increasingly referred to as the parish of St. Peter’s instead of the “Indian Settlement

The Indian treaty of 1871 designating St. Peter’s as a reserve with the purpose of prolonging its existence proved ineffective in the face of the strong demand for the sale of reserve lands. By 1875 half of the parish’s population had become non-treaty Indians and much of the missionaries’ painstaking work was undone. Farming had become a subsidiary occupation for many of the Indians, who drifted back to their traditional occupations of hunting and fishing. In 1908 the Dominion Government closed St. Peter’s as a reserve and a number of the Indians sold what lands they held to move north to the newly-opened Peguis Reserve. The old river lots were gathered into larger farms and the population of St’ Peter’s parish decreased.

Nevertheless, during this period the clergy of St’ Peter’s were active in the settlement in supporting the Indians’ cause and ministering to the needs of the parish’ Much energy was devoted to the Indian hospital which was opened in March 1896 during the ministry of the Reverend J.G. Anderson. This was located in the stone house which had been built for Archdeacon Cowley in 1865 and bequeathed by him to the church in 1887 for use as a hospital. Cowley had named the house Dynevor after the title given to his childhood friend and spiritual mentor, Canon Rice of Fairford, England. The term was applied to the post office in 1876 and eventually to the entire parish. The Dynevor Indian Hospital became the cornerstone of the church’s work in the district.

Additions were also made to the church itself’ The stone wall at the south end of the graveyard was dismantled and used to construct a chancel and vestry 25 feet wide and 15 feet long’ This made St. Peter’s the only early Red River church with a proper chancel’ The date of Tetris renovation is not known, but it occurred a few years after the church’s original stone tower, which had to. unsafe, was dismantled about 1880′ The bell tower was constructed in 1904 to commemorate St’ Peter’s jubilee and later topped with a spire. Two bells hung in this tower until 1962: The larger, weighing l4l I I 2 pound and cast in London’s famous White chapel foundry in 1850, was a gift of the Church Missionary Society; the other, weighing 112 pounds, was given to the Revering Cowley by an English friend in 1857′ This smaller bell, tuned to G sharp, was said to have the finest tone of all the bells along the Red River’

In 1941 the Dynevor Indian Hospital was sold to the federal government to be used as a tuberculosis hospital for treaty Indians and Eskimos, although it was later repossessed by the Anglican Church for use by the St’ Join’s Cathedral Boys;School. At the same time whew, smaller St. Peter’s Church was built on the west side of the river where the majority of the parish’s population was living.

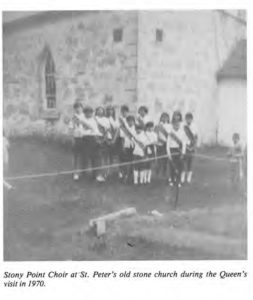

St. Peier’s Dynevor now stands isolated on the lonely east bank of the Red. In the cemetery surrounding its historic walls there are over 3,000 graves resulting from the epidemics which swept through the Indian population. However, grass fires have destroyed almost utter. wooden crosses which once marked their location’ Some restoration work has been done and the church is now used by the St. Peter’s congregation during the summer. The original hand-hewn pews and the carved pulpit and altar rail preserve the atmosphere of the missionary settlement. The church is a reminder of the dedicated work of the Anglican clergy and the Church Missionary Society, and of the first attempts by the Cree and Saulteaux Indians to adapt to changing conditions in the Red River Settlement. St. Peter’s Dynevor, now commemorated as an historic site, stands as one of Manitoba’s oldest churches and the focal point of the first Indian agricultural settlement in Western Canada.

Compiled by Donna G. Sutherland, Historian

This collection of sources consists of book titles, newspaper articles, web links, and primarily source material related to the history of St. Peter’s Church (St. Clements). The information is to be used as resource tools for students for research purposes.

Books

A Celebration of Red River Peoples (St. Andrews: Chief Peguis Heritage Park Inc, n.d.)

- This is a small booklet produced by Chief Peguis Heritage Park Inc on the history of St. Peter’s Church and its people.

Architectural Heritage – The Selkirk and District Planning Area by David Butterfield (Manitoba Culture, Heritage, and Recreation/Historic Resources, 1988)

- Article, photo, and sketch about the architectural details of St. Peter’s Church from pages 45 to 47.

Beyond the Gates of Lower Fort Garry 1880-1981, by R.M. of St. Andrews, 1981 (pages 63-65)

- Article and photos of St. Peter’s Church, the grave of Peguis, and various people including a list of clergy.

Beyond the Gates of Lower Fort Garry – A Sequel by R.M. of St. Andrews, 2000 (page 66)

- Photo of St. Peter’s Church from across the river.

Chief Peguis (Winnipeg: Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Recreation, 1984)

- This is a 12 page booklet discussing Chief Peguis and his connection to the church of St. Peter.

Chief Peguis and His Descendants, by Chief Albert Edward Thompson (Winnipeg: Peguis Publishers, 1973)

- This is a story about Chief Peguis and the St. Peter’s region, written by a descendant of the chief.

East Side of the Red 1884-1981 by Rural Municipality of St. Clements, St. Clements, 1984

- Article and photos of St. Peter’s Church, Dynevor from pages 189 to193

Family Connections: The 2005 Red River Descendants Reunion edited by Judith Hudson Beattie, Barbara Gessner, Shirlee Anne Smith, Donna G. Sutherland (St. Andrews: Lower Fort Garry Volunteer Association, 2009)

“Duncan McRae: A Community Builder,” by Brenda McRae- page. 82

- Photo and brief history of the main builder of St. Peter’s Church, Duncan McRae.

Geographical Names of Manitoba (Manitoba Conservation, 2000) page240

- Geographical information about the church and where it is situated.

If These Walls Could Talk by David Butterfield & Maureen Devanik Butterfield “St. Peter’s Dynevor Anglican Church (Winnipeg: Great Plains Publications, 2000).

- This book includes a brief article related to the history of St. Peter’s Church.

Peguis, A Noble Friend, by Donna G. Sutherland (Chief Peguis Heritage Park Inc., St. Andrews, 2003)

- Chapters 7, 8, 9, and 10 have information on St. Peter’s Church, as well as the earlier wooden church built in 1836.

Preserving Our History One Story At A Time, “Colonizing-Converting-Creating, St. Peter’s Church, Dynevor” by Jared Laberge (St. Clements Heritage Advisory Committee, Website Research Project, 2005) non-paginated

- Article about the history of St. Peter’s church and the missionaries and peoples associated with it.

River Road: Essays on Manitoba and Prairie History by Gerald Friesen (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1996), pages 64 & 65

- Details about St. Peter’s Church, the settlement, Peguis surrender & reserve.

St. Peter’s Church Dynevor (Winnipeg: Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Historic Resources Branch, 1984)

- This is a 12 page booklet giving the history of St. Peter’s Church, Chief Peguis, and Rev. William Cockran.

St. Peter’s: A Historical Study with Anthropological Observations on the Christian Aborigines of Red River by Michael Czuboka (Winnipeg: Unpublished M.A. Thesis, University of Manitoba, 1960)

- The detailed study of St. Peter’s reserve and parish. [This might be a bit too heavy for middle school research, but a resource to be aware of.]

The Anglican Church from the Bay to the Rockies by Thomas C. B. Boon (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1962)

- This is a general history of the Anglican Church in western Canada.

The Road to the Rapids: Nineteenth-Century Church and Society at St. Andrew’s Parish, Red River by Robert Coutts (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2000) pages, 7, 36, 47-49, 127

- Details about St. Peter’s Church, school, farm, mission, rectory, and the Ojibway peoples.

Magazine articles

Red and the Nile liked in graveyard in “Heritage Highlights” by Don Alken

- This is an interesting story linking a few people buried in St. Peter’s cemetery with the Nile River in Egypt.

Newspaper articles

Legislative Library of Manitoba – holds copies of almost all newspapers printed in Manitoba from the late 1850s. Some of the earlier prints are missing. Access to a large collection of digitized newspapers through www.Manitobia.ca

- Selkirk Journal 27 April 1998 – Preserving a Piece of History, St. Andrews woman lobbying government and citizens to restore St. Peter’s Dynevor Old Stone Anglican Church (Page 8)

- Selkirk Journal 25 May 1998 – Keeping history alive, or trying to anyway: St. Andrews resident still fighting to preserve St. Peter’s Dynevor Old Stone Anglican Church (page 11)

- Selkirk Journal 30 July 2001 Running on Faith: Congregation hopes to restore Canada’s second oldest stone church located in East Selkirk (page 2)

- Selkirk Journal 18 November 202 History under church floor: Evidence of 2,000 year old gathering place (page 3)

- Selkirk Journal 22 December 2003 Big Shoes to Fill: Chief Peguis book brings out qualities of leader who fought for aboriginal rights while embracing newcomers (page 2)

- Selkirk Journal 27 April 2007 Sharing the Legacy: Park commemorating Peguis planned near St. Peter’s Dynevor (page 2

- WinnipegFree Press 8 August 2002 Volunteers restoring old aboriginal church: $270,000 grant aids St. Peter Dynevor facelift (Local A7

- Winnipeg Real Estate News 5 September 2003 Land entitlement signed by Peguis Band (page 8)

- WinnipegReal Estate 22 November 2003 Land Surrender obtained through duplicity of officials (page 4-5)

Pictures

Archives of Manitoba

- Still Images Collection

- Hudson’s Bay Company Collection

Western Canada Pictorial Index at: http://images.uwinnipeg.ca/wcpi/

- Access to their database

Plaques and Sign Boards

- Peguis Monument – Kildonan Park, Winnipeg created in 1924

- St. Peter’s (The Historic Sites Advisory Board of Manitoba) located in front of St. Peter’s Church

Primary Resources

Archives of Manitoba

- Website can be visited at http://www.gov.mb.ca/chc/archives/

- To access records, a visit to the facility is required:

200 Vaughan Street

Winnipeg MB R3C 1T5

Phone: 945-3971

Toll free: 1-800-282-8069

Fax: 204-948-2008

E-mail pam@gov.mb.ca - Records related to St. Peter’s Church

- Parish Records of St. Peter’s Church (MG7 B5-1)

- Registry of baptism, marriage, and burial

- Journals and correspondence of Rev. William Cockran

- Journals and correspondence of Rev. Abraham Cowley

- Journals and correspondence of Rev. John Smithurst

- Journals and correspondence of Bishop David Anderson

Legislative Library of Manitoba

- Deposit for all newspapers printed in Manitoba from the late 1850s, postal records, community history books, and listings of all published material in Manitoba.

Web Sites

Archives of the Diocese of Rupert’s Land at: www.rupertsland.ca

- On-line access to the Diocese of Rupert’s Land Archives, but NOT the actual records. However, a general query will normally be answered quickly with information from their resources. They hold a large collection of primary and secondary material related to the Anglican Church in Manitoba and have records related to St. Peter’s and its people.

Archives of Manitoba at: www.gov.mb.ca/chc/archives

- On-line access to their site to view finding aids, but NOT actual records.

- Among the collections are journals and letters of various 19th century missionaries who were associated with the building of St. Peter’s Church – men such as Rev. William Cockran and Abraham Cowley. Also in the collection are sections of the baptismal, marriage and burial registry for St. Peter’s Church.

Church Missionary Society Archives, Birmingham University, Birmingham, England (Special Collections Department at: www.special-col.bham.ac.uk/

- Original Journals and letters of Rev. Abraham Cowley

- Original Journals and letters of Rev. William Cockran

- Both men were builders of St. Peter’s Church and led the services and peoples in Christian teachings.

Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Ottawa (Library and Archives Canada) at: http://www.biographi.ca/index-e.html

- Articles associated with St. Peter’s Church include:

- Peguis by Hugh A. Dempsey (Vol. 1X, 1861-1870)

- William Cockran by J. E. Foster (Vol. 1X, 1861-1870)

- Abraham Cockran by F. A. Peake (Vol. X1, 1881-1890)

Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa at: www.cellectionscanada.gc.ca

- On-line access to a wide variety of material related to St. Peter’s Church and its people; genealogical records, Indian Affairs

Manitoba Genealogical Society at: www.mbgenealogy.com/

- On-line access to a large collection of information in this organization that offer resources to help locate people from the past.

Manitoba Historic Resources, Winnipeg (Provincial Heritage Sites) at: http://www.gov.mb.ca/chc/hrb/prov/index.html

- Site No. 33 includes a photo and brief write-up about the provincial designation of St. Peter’s Dynevor Anglican Church Rectory, 47 Breezy Point Road, St. Andrews.

ManitobaHistorical Society, Winnipeg at: www.mhs.mb.ca

- On-line access to articles and photos related to St. Peter’s Church, Peguis and the history of the time when the church was built.

Western Canada Pictorial Index at: http://images.uwinnipeg.ca/wcpi/ (housed at the University of Winnipeg)

- On-line access to their database.