Laying the Rails

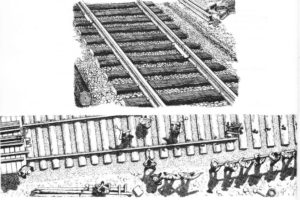

Railway lines are made up of two parts: the ties and the rails. The ties are wooden planks, about six feet long. The rails are made of steel. The rails are joined to the ties and to each other by fishplates and spikes.

Railway lines are made up of two parts: the ties and the rails. The ties are wooden planks, about six feet long. The rails are made of steel. The rails are joined to the ties and to each other by fishplates and spikes.

The ties ire placed across the roadbed exactly two feet apart. Men throw the rails onto the ties, and measure them to make sure they are in the right place. Then other men put the fishplates in place and hammer the spikes to keep the rails tight to the ties.

HARRY WILLIAM DUDLEY ARMSTRONG

“We began the work of constructing Canada’s great highway at a dead end,” commences section 3 of the third chapter of Pierre Berton’s The National Dream. This quote is drawn from the 4th chapter of a 245 page unpublished manuscript written in 1932 by Harry William Dudley Armstrong, the first resident of Beausejour. Although this manuscript was one of Mr. Berton’s more valuable research resources, his quotes and allusions to this material barely scratch the surface of this fascinating historical document. Mr. Armstrong was born I Aug., 1852 in the little hamlet of Bytown which the following year changed its name to Ottawa. Here his father, Christopher Armstrong, was a prominent citizen and the first Judge in this part of Canada. The Armstrong family was present at the laying of the cornerstone of the Dominion Parliament Buildings on I Sept., 1860 by the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII. The site had previously been occupied by a military barracks and had been known simply as Barracks Hill. At the time of the Royal visit “only a halfcleared space with stumps and boulders surrounded the buildings.” Mr. Armstrong had his own reasons for especially recalling the day. “Leaving the ground and turning onto Wellington Street, our coachman, gazing about, drove the carriage over a boulder, dumping the family out.”

At the age of 15, Mr. Armstrong became an article pupil to Sandford Fleming, then Chief Engineer of the Intercolonial Railway. (Fleming later became the Chief Engineer of the CPR and is best remembered as an advocate for the concept of standard time which he formulated. He was also later Knighted.) Here Mr. Armstrong worked in Mr. Fleming’s office on the second floor of the west block of the Parliament Buildings. In his memoirs he notes that among the first drawings he did in this office was one for the district engineer, Marcus Smith.

Mr. Armstrong’s parents were close friends of the McKay family who built a palacial residence on the east side of the Rideau River. As a child Mr. Armstrong played in the hallways of this home while his parents were attending balls given by the McKay family. Later this home became the residence of Canada’s Governor General. In 1867 Mr. Armstrong was a member of a volunteer Cadet Corps (the first in Canada, he believed,) which participated in the opening ceremonies of the first Dominion Parliament. “… it was a proud day for each and every one of us when the first Dominion Parliament met. We were selected to line the corridor between the main entrance and the Senate Chamber, forming a guard of honour for Lord Monck (the first Governor General) as he passed through.” Mr. Armstrong met every subsequent Governor General of Canada, most of them while on tour to various parts of the Dominion.

Mr. Armstrong continues.

Following the opening of the first Session of Parliament, I had the opportunity of meeting, at my Father’s house, many of the ‘Fathers of Confederation’ among whom I remember particularly Sir John A. MacDonald, D’Arcy Magee, Mr. Tupper, and Leonard Tilley. Colonel Grey and we boys (of the Cadet Corps) frequented the public gallery of the House of Commons during debate and compared the oratorical powers of the individual speakers. I was impressed by Dr. Tupper’s speeches and was disposed to think him the most fluent, dignified and powerful of the prominent debaters. Mr. Armstrong continues with a fascinating account of his recollections of the murder of D’Arcy Magee on 7 April, 1868, concluding with these lines, “… Morris and I hastened to town as soon as we could and saw D’Arcy Magee’s blood on the sidewalk where he fell in front of Mrs. Trotter’s boarding house.

In 1870 Mr. Armstrong completed his apprenticeship with Sandford Flemihg and secured his first employment as a draftsman and instrument man for the Great Western Railway. His autobiography is filled with many fascinating insights into railroad building and life in general at that time, one of which we may mention here, “Living was cheap in those days; we paid $3.50 per week for board and room and good meals we got. At noon the regular hotel dinner was our lunch while at 6:00 they gave us a special dinner, always two joints on the table, vegetables and pies of all kinds and as much draught beer as we l,’anted, all included for $3.50.”

In 1874 Mr. Armstrong became Assistant Engineer for the waterworks commission of Toronto for the installation of a system of waterworks throughout the city. Then in 1875 he became Assistant Engineer in charge of construction for the Canadian Pacific Railway. Here his narrative must be related in its entirety.

“CHAPTER IV”

After years of public discussion and much controversy as to the practicability of constructing a railway across the continent surveys were commenced in l87l under Sandford Fleming as Chief Engineer and carried on very extensively up to 1875. … At that time the idea was to make a combined rail and water route. There was no settlement of any kind between the head of the Great Lakes and the prairies of Manitoba and little or none beyond to the Pacific Ocean.

On May 25, 1875 a party of engineers and assistants were collected at Ottawa and began a journey to Winnipeg; many of them had never been more than a few miles from home and this experience was a novelty. Others joined the party at Toronto and besides these, there were two or three others travelling the same route. When baggage and engineer’s paraphernalia was gathered on the railway platform, two or three bundles of walking sticks, umbrellas and hat boxes appeared which the party could not understand as necessary for survey work in the wilds and became objects of much interest. The owner proved to be a man of diminutive proportions with a strong English accent, plenty of assurance, but a very limited knowledge of the country he was going to. However he and the other stranger soon became part of the party and all arrived safely at Owen Sound that evening.

Steamer berths on the “Quebec” had been reserved for the Government party and as each one stepped to the purser’s office to get his berth, he was asked his name 33 and if he was one of the government men. Little Mr. B. got his chin up to the wicket and was asked the question, to which he replied in a very important manner; “No, I’m an English officer going out to shoot.” which was highly amusing to the others standing around. However he got stowed away in the boat and we sailed that night for Prince Arthurs Landing at the head of Lake Superior, so named after Prince Arthur of Connaugh, now called Port Arthur. Things were not quite satisfactory on board in the way of grub and service and at Sioux Ste. Marie the old side-wheeler steamer “Frances Smith” came alongside with Captain Tate Roarson in command. He had no passengers and being a congenial sort of man, the party was anxious to accept his offer of a free trip and the best of everything he had for the balance of the journey. Unfortunately, as we were about to step aboard, we discovered that he was only going to Prince Arthurs Landing while we had to go on to Duluth in Minnesota. So we had to stay on the Quebec and make the best of it. We arrived at Duluth in due time and put up at the Clarke House. This was the best hotel then. Duluth didn’t appear to be in a prosperous state for it may be said the grass was actually growing in some streets, but the Northern Pacific Railway began to give an impetus to business although it had just opened and the trains were running semi-occasionally west to Moorehead and Fargo. After a couple of days here, during which some of the party spent their time in revelry we got away, westward bound. One night during our stay, I had gone to bed early in a double bedroom and was awakened in the middle of the night by my roommate, Dave R., coming in. Succeeding in getting so far towards his bed he remembered he had been taught to say his prayers. He promptly got down on his knees. I thought he was extremely pious to spend so much time over it so making an investigation, discovered that he had simply gone to sleep! Aroused and persuaded he rolled into bed. Another member of the party, Mac N., who had been out in the wilds before made himself a celebrity by getting incapacitated almost every hour and turning up regularly again as if nothing had happened. It was a slow journey and afforded some amusement in helping the train over some floating bogs and other obstructions until we finally arrived at Moorehead and crossing over to the Dakota side of the Red River, where we put up at the Railway Hotel where the convivial section of the party sought occupation similar to Duluth and were not long in finding it’ Among other readily acquired acquaintances was one who represented himself as a United States Senator, who evidently took great interest in these travellers and enjoyed more of their hospitality than he extended of his own, although showing them all the sights and playing the role of Senator in a very fair way’ I was somewhat surprised and much amused not many months later to find the “Senator” blacking boots at Bob Cronn’s Hotel in Winnipeg.

After a couple of days at Fargo, we got a stern-wheel steamer going down Red River to Winnipeg’ Loaded with freight and passengers – the best sleeping accommodation to be had was a blanket on the top deck and nights were fairly cold. Anyone who has travelled the rivers of the prairies knows how tortuous they are.

This steamer would bump up against a bend on one side, swerve around wrong end first and after tying up to stumps here and there, got herself pulled into line again. Some of these bends were so long that members of our party would jump ashore, walk across the prairie a mile or two, sit down and wait for the steamer to come round the bend.

On the morning of 7 June, 1875 we finally tied up against the north bank of the Assiniboine River at its junction with the Red, close behind the Hudson Bay Company Post. There was no wharf or landing and we got ashore on planks. On this occasion we found 4 inches of new snow overlaying 4 feet of mud when we left the planks. Scrambling up the bank as best we could, we went in search of hotel accommodations which were then very limited and much in demand owing to influx of settlers and commencement of railroad construction’ After hunting about some time, we got billeted about the “village” (for that’s all it was then). Two others and myself found room and board at the Wolseley House kept by Mr. Fonseca – Fort of Teppman’s Hotel, where the proprietor was also waiter, host, and everything else. Not many years after that he became City Alderman and one of the wealthy and respected citizens of Winnipeg. The snow we encountered on arrival melted away very quickly and then was revealed to us the devastation caused by the grasshopper plague of the year before. Not a blade of grass or green thing was seen. Even lace curtains in some windows had been eaten to pieces. Some remaining swarms passed overhead going south but miriades alighted and walking on the few wooded sidewalks existing was slippery work as they were crushed underfoot.

Our party was divided up now and some of them went back east over the Dawson Road to revise location of a portion of proposed Canada Pacific Railway as it was first called. They went to Rat Portage (Kenora now)’ Those of us destined for work from Red River eastward spent a few days in Winnipeg getting our camp outfits and supplies. We had a temporary engineer’s office over Scot’s Furniture Store where I remember well painting a lead rod for my own use. We proceeded down the Red River to Selkirk, a small village not far below what was known as Lower Fort Garry, and at that time the proposed crossing of the CPR main line.

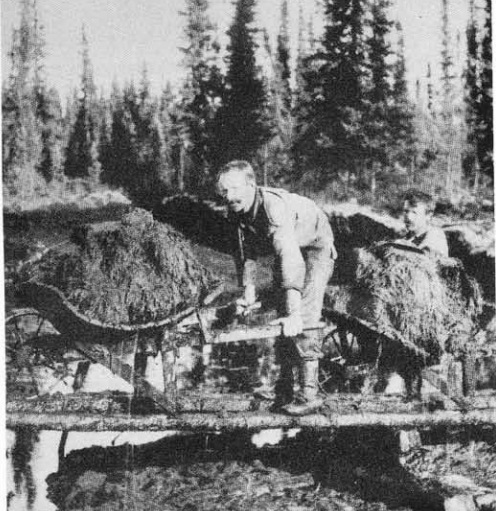

In the afternoon of a very rainy day we landed from a small stern-wheel steamer on west bank. We crossed via ferry on a cable propelled by the current andbegan our first actual experience in camp life, its pleasures and discomforts. The beginning came in the way of discomfort, for in a pouring rain we tramped into the woods on the river flats, large timber, thence underbrush and thick foliage and here our tents were pitched. An attempt was made to provide dry surface to lay upon but absence of dry wood, spruce or balsam boughs, made it impossible, nothing but wet leaves and a mud bottom. A waterproof sheet and two pair of Hudson Bay blankets comprised the bed arrangements and as for cooking, this was out of the question. So our first meal consisted of hardtack and canned corned beef. The novelty of the experience was enough to offset the discomfort and next day we began locating the line of railway eastward from a Survey Crew. point only a quarter mile from the river up on prairie level – dry ground – (I often have wondered who the individual was who hadn’t sense enough to pitch our lastnight’s camp up there.) My position was Assistant Engineer but I began by referencing the centre line hubs behind the party locating.

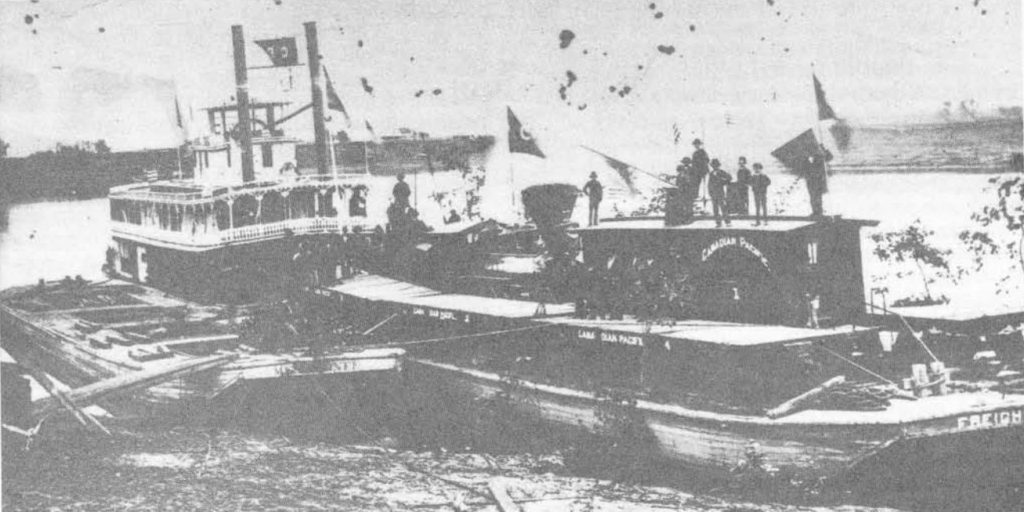

Before writing further it is necessary to refer to the personnel of the government employees and contractors of the “Manitoba District” with whom I was connected during the following six years. At Winnipeg were Rorran, District Engineer; Thomas Nixon, Purveyor; Jacob Smith, Draftsman; Thomas Jefferson Thompson, Division Engineer; At Selkirk were Sifton and Ward, Contractors for grading contract 14 extending from Selkirk to Cross Lake, 77 miles; Sifton and Glass, contractors for telegraph line eastward; Joseph Whitehead, contractor for grading contract 15, Cross Lake to Rat Portage, 37 miles, and also for track laying over both 14 and 15, also for the branch St. Boniface to Selkirk east (St. Boniface being on the east side of the Red River opposite Winnipeg). There were no bridges over the Red or Assiniboine Rivers at this date nor any railway nearer than the Northern Pacific (US). So we began the work of constructing Canada’s great highway at a dead end, relying upon the stern-wheel steamers and flat boats for all material and supplies of all kinds because the grasshopper plague of 1874 had stripped the country bare.

Simultaneous with initial work, the government had let contracts for grading and track laying from Prince Arthurs Landing to Rat Portage and also on the Pacific Coast extending east up the west slope of the Rocky Mountains but nothing between the Red River and the Mountains except a one-wire telegraph line and this wire was later mostly used up by halfbreeds and immigrants in mending cart wheels and wagons when the whole location in general of the railway was changed from Selkirk west’ So six years of my life was spent between Winnipeg and Rat Portage – only a total of 136 miles.

After two or three days referencing hubs, I was placed at Stony Prairie, later called “Burgoyne” again “Beausejour”, which is now a thriving town of 3000 inhabitants. It was a dry ridge l6 miles east of Selkirk and where the contractors were anxious to set sub-contractors to work. Freeman and Shultz’ Bob Bullock came there with a team and scraper from Ontario and did some work for F. & S. He settled permanently at Selkirk, becoming a prosperous man. I may claim to have been the first resident. With me were a rod man, axe man and a cook and I began cross-sectioning and staking out the grading’ We occupied tents at first and our supplies of government rations were sent from Winnipeg by oxcart which floundered through hay marshes with about 500 lb. loads. We got ample quantities of bacon, beans, flour, tea, coffee, dried apples, desiccated potatoes, molasses, sugar and canned fruit and were quite happy. I had a section of 13 miles and was situated near the middle’ A good deal of it was poplarwoods westward and after theBrokenhead River (3 miles east of camp) mostly spruce and tamarack swamp through which we waded knee deep among the stumps day after day, while at the depth of 4ft. there was ice all summer long; top surface was a foot of moss.

Among various duties the resident engineers had to perform to keep them busy (besides staking out work and making estimates for contractors, sub-contractors and station men) were inspecting ties and keeping up the telegraph wire on their own section of 13 miles, also doing the operating for everyone connected with the work “gratis” and keeping open house for all comers; – Here is a sample of one day’s work but not much out of the ordinary – Wednesday, April 18, 1877 – Left home with Steele an axeman to cull ties at east end – found boots hurting my feet and with difficulty reached Bear Creek – stopped for lunch, boiled tea and enjoyed the meal; after a rest walked on to end of section – l0 miles from home. Inspected ties working backwards and got through at 6:00 and then had 8 miles to go. Feet got very sore – with great difficulty made 4 miles – then had to give it up, took off socks and tried boots alone for a couple of miles, then took off boots and tried walking in socks alone, couldn’t keep this up long. Finally Steele took off his moccasins and lent them to me while he wore his rubbers only. Fairly played out we reached home at l0:00 and in a few minutes were going for a hearty meal. A smoke afterwards, a little reading, then to bed pretty well tired out. One of the hardest days up till now. Fortunately it was a fine day and bright moonlit night.

Our campsite was a dry ridge and no water – so we had to go to nearest hay marsh, but found we could get water by digging a well in railroad side ditch nearby and here, on Sunday, would wash our socks and underwear – and ironing with a smooth boulder on a flat rock – of course we gathered what rain water possible from tents. Common garter snakes were plentiful and would get into blankets on ground till we devised cots by stretching Hudson Bay cart covers on two poles supported by crotch sticks driven into the ground.

Mosquitoes, black flies and bulldog flies were very thick. Prairie chickens were plentiful close by and furnished change from bacon – a cart trail was built alongside railroad grading – one day about middle of July there came by my tent a wagon drawn by two oxen carrying a plough, harrows, rake, scythe and other tools, seed potatoes, fowl, tent, some food supplies, a wife and * 35 six little girls, while the owner walked behind with a

couple of cows. His name was Campbell and he had come from Perth, Ontario. He went on east to the Brokenhead river about 100 ft. wide and with a fringe of scrub oak on the bank – here he pitched his tent and housed the family – turning loose his cattle in the hay marsh. Next day he ploughed a furrow in an open space of scrub prairie – put in seed potatoes with the aid of the children – then ploughed another furrow over to cover them, repeating this process he had a good sized patch in crop. This being done, he took his scythe and mowed a quantity of marsh hay which with the aid of wife and children he stacked. I measured the hay myself, which he sold to the railway contractors. He was glad to take our surplus bacon and beans in exchange for his fresh milk and eggs. He built a log house before winter set in, extended his farming operations and 20 years after went out, a well-to-do man.

Horses did not take the place of oxen for freighting until freeze-up in the fall, but during winter we had fine sleigh roads everywhere, but there wasn’t “everywhere” to go – just to Selkirk, Winnipeg and along the railway right-of-way. The flies that summer were unbearable; – I remember very distinctly one occasion walking through a swamp carrying my level on one shoulder and something else. I counted on second joint of forefinger of left hand no less than 9 mosquitoes with their bills sunk to the hilt in that space and they were equally thick on every exposed part of face and hands. Netting was worn at times but in hot sun was almost worse than mosquitoes. They were equally troublesome at night when they are quite as busy and their buzzing noise is as bad as their bites.

Towards the end of this summer (1875) the engineers were all located on their sections between Red River and Prince Arthurs Landing and the Government began erecting houses for them – Big Rory Mclennan – champion sledge thrower later, now Colonel Mclennan of Alexandria, had a contract to build five of them and started the first one at Stony Prairie for my occupation and the second one about 1000 feet distant for the Division Engineer. They were built of flattened timbers – 36 ft. square and I 1/2 storeys high, joints filled with mortar – I got into mine first, even before the fly season was over, but for some nights could not sleep indoors because of mosquitoes getting in through cracks and down chimneys, so we resorted to tents again – pitched on a gravel space, spread buffalo robes and blankets and built a smudge inside, which expelled the greater bulk of the insects, and having no grass to hide in they took to the roof. Closing up tent with pins, leaving no opening, we then took candles and burnt off each individual mosquito inside the canvas. Then comparatively free, only disturbed by awful buzzing outside, we slept. Weather became colder at night and we returned to the house.

In this way we existed the first summer and autumn and after five months of daily walk averaging 7 or 8 miles through swamps and muskeg, wet to the knees in mud and water, came a sensation; the frost set in work stopped to a great extent and we began to hibernate – our first winter in the country.

The engineers on contract l4 were A.N. Motesworth at Tyndall; myself at Beausejour; John Molloy at Shelley; 36 F.F. Blanchard at Rennie; H. Forest at Telsford. On Contract 15 were Dave Roger at Ingolf; Waters at Kalmar; Henry Carre, Division Engineer at Invez; Kirkpatrick at Ostersund; Rockliffe Fellows at Keewatin (just west of Kenora and end of our Manitoba District).

The telegraph line from Winnipeg, via Selkirk, reached Beausejour, (I should say Stony Prairie) on 14 July, 1875. Rowan arranged with the contractors that for free use of their line from Winnipeg to Selkirk, we engineers would learn telegraphy during the winter and do business free for the contractors on the government wire which was run into all the engineers’ houses and I myself set up the instruments in each. T.J. Kennedy, rodman with Kirkpatrick, became quite proficient, much ahead of any others, though they all, and wives as well, picked upenough knowledge to converse with each other and this made companionship possible when personal visits were impracticable. Kennedy and I were closely connected in railway work 20 years later and he died while president of the Algoma Central Railway. Of course we got the benefit of any conversation between any two offices – if we chose to listen – and once we heard someone ask Kennedy, “How’s Mrs. Carre’s hens getting on?” But the chief benefit of the telegraph was in getting news from Winnipeg – calling the doctor on the line when needed, etcetera. The first paid message was sent by my hand – it was calling Dr. Hanson from Kenora (Rat Portage) to attend wife of Campbell at Brokenhead when her seventh little girl was born. We had a weekly mail dropped from Winnipeg by packer and any traveler along the line carried letters either way.

There wasn’t much grading going on during winter so it was decided to run a trial line which might improve the railway location about 75 miles. I was ordered to run east and meet Forest coming west, both to be on the same tangent. Accordingly I got together four trains and drivers and about Jan. 20, 1876 commenced at Stoney Prairie having my own men and party made up of odds and ends from Selkirk – weather very cold – snow deep and we encountered much windfall and brule. Trail for moving camp had to be broken daily on snowshoes which froze hard enough during night to carry dogs and toboggans next day.

Our dogs were not the best and sometimes the leader would choose to go over the top of a log and the next dog would prefer to crawl under, so there would be a mix-up. Then the halfbreed drivers would be much in evidence and a wholesale battering of the poor animals would ensue and might have been avoided by better management and more humanity. However we had to get along, anxious to get more than halfway before meeting Forest. In this party of the “Whoop-up” line, I had a young Irishman named Stanley, his first winter in Canada. He was accustomed to his morning bath and went out every morning stark naked, rolled himself in the snow at 40 below Zero, and returned to a warm tent (heated by a sheet-iron stove) and rubbed himself dry. How many of my readers could endure that, I tried it once – once was enough! We had a good commissariat and met Forest’s party after overlapping them about 70 feet and getting in a few chains more distance than they. The whole outfit then returned to my house where tents had said, partner, to of house” were discarded and floor space occupied while two cooks provided grub and then all left but my own cook and two men. We settled down then to continue our telegraphy, read, write and visit our nearest neighbor, Molesworth, only 9 miles off, but we could tramp there in an hour and a half, returning at rnidnight.

As to cold weather and frost bite; – I met Tommy Watts, a florid hot-blooded Englishman, who acted as timber inspector, coming along one bright frosty day. His ears and nose were frozen white while the perspiration was running down his cheeks. We put in our first winter very pleasantly. Just before Christmas several of the Assistant Engineers gathered in Winnipeg and those who were my nearest neighbours on the line formed a party to eat Christmas dinner at my house. Mrs. Thompson fixed me out with Christmas pudding and all accessories. We drove from Winnipeg to Tom Taylor’s hotel near Lower Fort Garry on 24 Dec., spent the night there and on the counter in Black’s store nearby and had our first introduction to a Red River Dance as follows: After tea we bundled into a box sleigh and Tom drove us a few miles down the river on the ice. Bringing up at a large log house, we all entered to find it one big room with a ladder to the attic. Kitchen stove in one corner and an enormous bed in another, table and chairs moved to the walls. Here were 4 or 5 young halfbreed bucks and as many dusky maidens. A fiddler commenced; then was passed round to each a black bottle of whiskey and tin cup (one cup for all) during preliminary arrangements for partners. The whiskey went the rounds a second time and we stood up with our partners for the first dance. Hardly had the Red River jig commenced when there sounded a scream and general commotion. It happened that the big bed conlained an infant. An old Granny hitherto unnoticed sat in the corner; someone sat on the baby. Granny started a quarrel and then pandemonium reigned. I grabbed my cap and coat rushed out, the rest followed and we scurried back to Tom Taylor’s comfortable hotel to conlime part of the proposed evening’s entertainment.

Christmas morning 1875, beautiful, fine, bright and cold. Molesworth, Blanchard, A. Mclean and Gordon, Dave Rogers and self left Taylor’s on foot and reached my house 18 miles walk by evening, where we found our Christmas dinner all prepared in fine shape. There was of course no lack of drinkables for whiskey was recognized as a necessary commodity, just like tea or coffee in those days, on such occasions. So we spent a very enjoyable time, all of us bachelors.

Work during the summer of ’76 was similar to the last, walking in swamps and muskegs along the line, looking for offtake ditches, etc. The government specifications were very specific regarding drainage and our subcontractors, mostly from the USA railroads, were not accustomed to taking out side ditches to regular grades and distributing material to form embankments, but wanted to borrow anywhere near any regular pits, so we had a good deal of trouble in breaking them in. They said, “We didn’t come here to dig canals.” Sifton, his partner, his engineer Hollinshead and Sifton’s sons used to come out to Stony Prairie to shoot prairie chickens and of course the Government engineer’s houses were “open house” for them, as we were free to utilize their camps at will and we were seldom a day without visitors. In fact life along the railway construction in those days was like one large family. There was hospitality, helpfulness, general friendship, good nature and contentedness all about. I suppose it is the same among all pioneer communities. I was in Winnipeg on24May that year, ’76 and there was a celebration going on. Games, Band playing, foot races, etc. There was a fearsome militia maintained in Fort Osborne, kept there since the Wolseley expedition of 1870 to quell the first Riel rebellion and the Northwest Mounted Police were also quartered here. These men, especially the officers, were prominent at all public entertainment. So they were on this 24th of May. I saw a goodlooking black horse being ridden about by Tommy Haverty, who with his brother John, kept a very good hotel on Main Street near the Hudson Bay Store (now). I asked him to let me mount him, which he did. A sidewalk raised two or three feet above the ground looked tempting, so I gave him a chance to show his jumping prowess and found him quite able and willing. The horse belonged tq Alexander McMiken, a banker. I bought him then and there; when it became known, my friend who knew him exclaimed, “You can’t ride that horse – he’ll kill you.” (Because McMiken couldn’t ride him) and nobody could put him in harness. However it was too late.

I rode him to Beausejour without difficulty but he soon proved to be the most expert kicker and rearer. He could stand perpendicular on either fore or hind legs and many a time I hung onto his neck with one leg and an arm, but he never got me to the ground. He would crawl over the soft marsh like a cat but if he had wind on his back and flies bothering him, he would refuse to go, however I made good use of him and in the winter of ‘761’77 at 40 below Zero on hard snow roads, he would take me to Winnipeg and back, 78 miles, in 12 hours. Let it be known that this is a warmer way of travelling than driving in a sleigh. So much for my horse called “Boots”.

Work during the winter of ‘761’77 was light and we spent most of the time indoors with frequent visits to Selkirk or Winnipeg and telegraphy as amusement.

There was no railway running out of Winnipeg in June 1877, when in a wedding trip, in which I was much interested, and it was accomplished by use of a concord buggy and ties via Selkirk to Beausejour. There was a great deal of rain this early summer and the roads were almost impassable. Horses balked in a deep mud hole near Mapleton, necessitating my getting out of the buggy up to my knees in mud and water. However the journey of 39 miles was completed by nightfall when the first bride took up residence in the first house built here.

I had to take over Molesworth’s section in addition to my own, as he was placed on the grading from St. Boniface to Selkirk east, and I had more distances to walk, even on some days – 15 miles to work – 3 or 4 hours at work – and a walk home of l5 miles and carrying a lead on the shoulder, this made a fair day’s work. 4:00 A.M. to 10:00 P.M. Engineers of the present day would not attempt such, but claim 8:00 A.M. to 6:00 P.M. is even too long.

Jefferson Thomas, Division Engineer, and his family came to Beausejour in the summer, so we had neighbours nearby, besides the sub-contractors and Campbells.

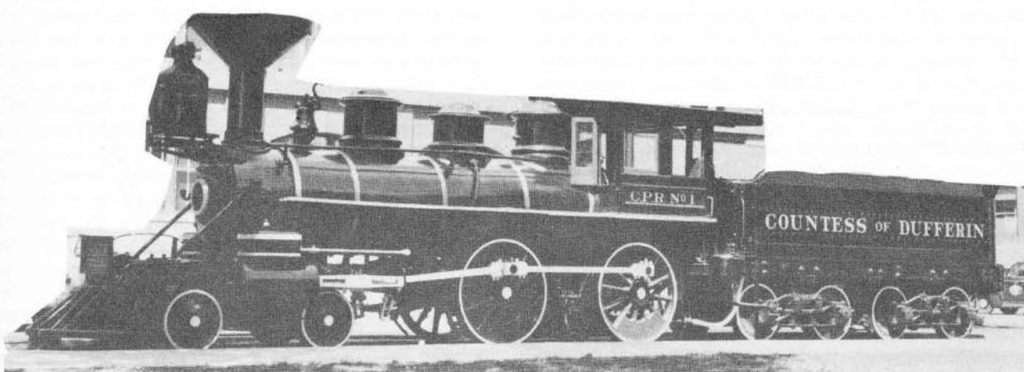

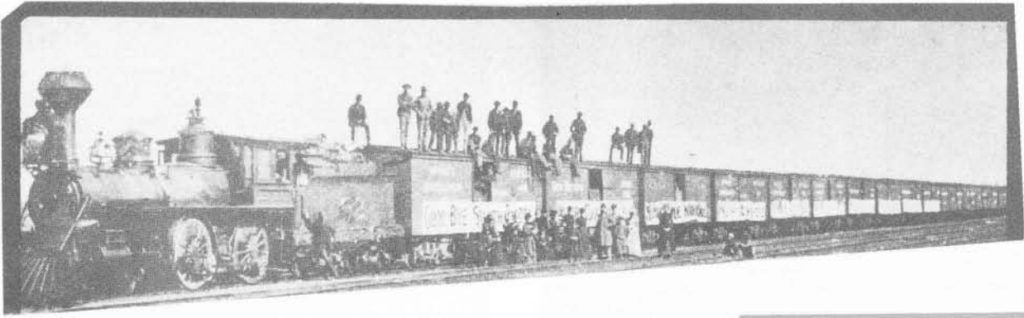

The “countess of Dufferin” arrives in llinnipeg. The first railway engine in western Canada.

About the freeze-up of “7’7, Watters, Assistant Engineer at Kalmar on contract 15 was drowned, and I was ordered to take his place. Leaving my wife in Winnipeg, deserting my abode at Beausejour, I went to Kalmar. I found tfie body of my predecessor laid in a rough coffin on the top of two stumps near the house where it remained for some time (frozen) until ice on small lakes was strong enough for teams, when it was removed to

Winnipeg.”

Having transfered his headquarters from Beausejour to Kal*a. in Section 15, Mr. Armstrong became involved in some of the most difficult construction work the railway had encountered to that point when it undertook to chisel its way through the ancient rocks of the Canada shield. No less formidable were the vast stretches of seemingly bottomless muskeg. The Armstrong’s eldest son was the first child born within the CPR right-of-way in Canada and the Armstrong family were also passengers in the first private railway car on the line.

“Christmas of 1878 we decided to spend in Winnipeg with my wife’s family, J.B. Spencer. Her father was the first collector of Customs and Inland Revenues for Manitoba (1871). The end of track was at Cross Lake and 22 miles intervened between Kalmar and that. Having no horse vehicle, I made a hand sleigh and on beautiful clear cold morning 22nd Dec., put wife and baby on it wrapped in blankets and buffalo robe – then my two men hauled it while I walked behind with the l5 year old maid. We stopped for lunch with my confrere, Dave Rogers, at Ingolf and at dark reached Whitehead’s headquarters at end of track.

Having got the family comfortably housed for the night, I looked about to see what train accommodations there was to reach Winnipeg. I found the “Countess of Dufferin” with empty flat car was going next morning, 38 but no caboose or exen a boxcar. This wasn’t too promising with temperatures 25 degrees below Zero; but there was an empty cattle car, just a flat with fence round it of slabs and a foot of frozen manure on the floor. In the woods nearby I saw a small tent pitched. Investigating, I discovered it was not occupied so with the aid of my two men, took it down and nailed it up in the front end of the cattle car. Then I secured a bail of hay and spread it thickly inside’ Next morning I put our robes and blankets down and got the party inside’ This included wife and baby, maid, two men, Dr. Baldwin, Frank Meyers and self, which filled the tent. Just before the train started, an old government pony which had been lost since summer was loaded up in our car and soon got his head inside the tent to feed on the hay, but otherwise didn’t interfere with our arrangements. It took all day to reach Winnipeg, having stopped at Beausejour to warm up and get something to eat at Thompson’s house. The thermometer registered 25 below. Baby had nose frozen and a flask of Sherry wine froze also, but we were protected from the wind at least. Trainmen road on the engine and several men riding on the open flat. One man had his legs frozen to the knee. When we returned to Kalmar the track had reached there and we had a boxcar to travel in. However, my tent and cattle car of Dec. 23, 1878 I call, and I believe it was, the first “Private Car” on the Canadian Pacific Railroad and the baby of that trip was the first child born within the right-of-way of the railroad. ”

In April of 1881 Mr. Armstrong was asked by General T.L. Rbsser, Chief Engineer of the CPR, to become his principal assistant engineer in the head office in Winttipeg, located in the new Bank of Montreal building. (General Manager Van Horne also had his office in this building.) During this period Mr. Armstrong came in close contact with all of the principal figures involved in the construction of the CPR line including G.S. Shaunessy, Assistant Manager, as well as George Stevens and Donald Smith, Directors of the CPR. Later having accepted an offer to become Division Engineer in charge of construction in Lake Superior District, he was responsible for transporting over the gaps which then existed in the line, the troups sent from the east to quell the Riel uprising.

Later employment took him to every province of the Dominion. In 1896 he returned to Manitoba to become Divisional Engineer for the firm of McKenzie and Mann, contractors for the construction of the Canadian line into Dauphin. Two streets of that town subsequently bore the names of two of his daughters. For the next two years he was Divisional Engineer for the CPR for the building of the line through the Crows Nest Pass. Then from 1905 to 1908 he worked for the CNR and among the bridges he constructed was that over the North Saskatchewan River at Saskatoon. He retired at the age of 75 from the Ontario Department of Public Works where he had been Assistant Engineer for the previous l0 years. He was also a Charter member of the Canadian Society of Civil Engineers (later Engineering Institute of Canada) founded in 1887 and at the time of his death on 2nd Aug., 1937 in his home on Roxborough Street in Toronto, he was one of the last six surviving Charter members of that Society. The previous day had been his 85th birthday. He was buried in St. James Cemetery, Toronto.

Working Crews – CPR

submitted by slh

The country’s first railway boom happened in the early 1850’s when the Grand Trunk Railway was built from Sarnia through Toronto to Montreal and on to the sea coast at Portland Maine, a distance of 800 miles. Between the years 1854 to 1857 about $100 Million in foreign capital was pumped into Canada for the purpose of building railways. Sanford Fleming, a civil engineer, who became Chief Engineer of the Northern Railway in 1855, was largely responsible for the railway decisions of the day.

Talk about a coast to coast, Atlantic to Pacific railroad, really began in earnest back in 1862 when 35 year old Sanford Fleming placed before the government of the day a carefully worked out plan for a “highway to the Pacific.” It was very explicit to the last detail, was to be built in gradual stages, would cost about $100 Million or more, and it would take about 25 years to build.

People listened to him, he was well respected as an engineer and after all, he had just completed 800 miles of rails, successfully. However, this was a very ambitious project and the politicians were in disagreement over the dream of Sanford’s. Some politicians were very fired up over it and wanted to get on with the venture, like John A. Macdonald, a young Lawyer and Attorney General for Upper Canada and some were reluctant because of past history and the costs. Mr. Edward Blake, another young Lawyer, who spoke out against it was doubtful about the value or need of a link with the Pacific. These differences of opinion led to serious arguments and debate between the politicians and government of the Upper and Lower Canada legislature.

The first task in building the railroad was to unite the country into one nation. After many setbacks, this task was finally completed in 1867. One of the conditions of the “BNA” Act was that an intercolonial railway, connecting the Maritimes with the rest of Canada must be built immediately. Sanford Fleming was assigned this project for the Maritimes and to formulate plans for a rail route to the North West Territories.

This plan of penetrating further west set off a series of surveys needed to plan the route, the grades, and expected settlement areas. All this activity was never fully explained to the people of Upper Canada and further west, and it upset the Metis people of our own area in the Red River settlement. The Metis indicated their disapproval in open resistence and a small disagreement took place in 1869170.

Manitoba became a province in 1870 and shortly after they were admitted to Confederation, extensive plans for the development and colonization of the newly formed province were started.

At the same time, fearing that the expanding United States might want to take over the colony of British Columbia, the government made an agreement on July 7, 1870 that Canada would complete a railway to the Pacific within l0 years and actual construction would start in 2 years if the Pacific colony would enter confederation. On the basis of the 1870 agreement, British Columbia became a province on July 20, 1871.

In 1871, Sanford Fleming again conducted surveys, at once, so that decisions on the route and investigations into the potential resources could be made’ As information was brought in from the field surveys it was collated by the government along with all other reliable data known about the west.

The Dominion Land Survey that was conducted also contributed to the direction of settlement as homesteads could be filed only on land already surveyed and settlement, in general, followed the survey.

Sanford Fleming decided the route on the basis of his own survey and others carried out by Palliser and Hind. Itwas decided as early as 1871 that the railroad west of Lake Superior be built from Fort William to Selkirk, there to cross the Red River over the west bank, then on t0 cross Lake Manitoba at the Narrows of Lake Manitoba, and then proceed northwesterly toward Edmonton. It is to be noted that the selection of a northwesterly route toward Edmonton and crossing at Selkirk, was also dictated in Palliser’s Report, in 1857.

The crossing of the Red River at Selkirk by the proposed railway was dictated then by geological and professional engineering considerations. A railway bridge built across the Red at Selkirk would have the benefit of more stable banks than existed further upstream. More important, the bridge and railway would be safe against flooding if built at Selkirk. The site of Winnipeg it was known, had flooded about 7 times during the previous century. Selkirk, sitting on a high ridge of land, had never been flooded. During the great flood of 1826, when the site of Winnipeg had been completely flooded, the land of Selkirk had sat 15 feet above the highest level attained by the flood waters.

The government of Canada had got rid of many obstacles to the proposed railway, but now had to decide on a route and to find the money to finance the building of it. The next two years were spent trying to encourage private enterprise to get involved, construction-wise and financially.

It was finally decided that a private company would construct the railway between Ontario and the Pacific with federal aid for the project.

Contractor chosen would get 50 Million acres of land along the right-of-way and some cash subsidy of about $30 Million. Hugh Allan of Montreal was chosen (closely linked with US financiers) providing he broke contact with his U.S. connections. In 1873 the storm broke re: Pacific Scandal and the Liberals accused Macdonald and his Tories of receiving considerable funds for the 1872 election campaign from Hugh Allan and his American backers. The government created a “Commission of Enquirey” and evidence was to prove the accusations partly true. Criticism became so serious and the debate so bitter that Macdonald and his cabinet were obliged to resign.

Alexander Mackenzie took over the running of the country in 1873 and continued until 1878. During this period he believed that the pace of construction of the railway should be only as fast as the government finances would allow without strain. The defeat of Macdonald meant the end of Allan’s contract and the end almost of the railway scheme itself.

By the end of 1873, there followed a worldwide depression which involved sharp cutbacks in all building and railway construction in the USA and severe stop of all credit in Great Britain. This also caused a steep decline in all foreign trade. By 1876, the country was generally suffering from a depression, that grew slowly worse until 1879.

In 1876 the Intercolonial Railway was completed and provided the first all Canadian rail connection between Montreal and the eastern coast. It extended over 700 miles and touched upon 6 Atlantic parts.

The present site of East Selkirk was first seriously surveyed by Palliser and Hind in 1857 and again in about 1862 it was a part of the surveys of route, grade and settlement pattern of the proposed railway of Sanford Fleming’s intercolonial route. Then, in about 1871, Sanford Fleming again conducted further surveys of a more serious nature.

ln 1875176, the government proceeded to map out Selkirk, as a proposed townsite in anticipation of San- 4t ford’s proposed rail route. It would be situated on the east side of the Red River and would have a large “engine house” to accommodate the many engines for needed repairs and maintenance. Then in 1878 the land was levelled and prepared for the building of the engine house. The bridge across Cook’s Creek was built in 1878 and was for the railway line to extend to the Roundhouse across the creek and ultimately on to the east slough at Colville Landing.

Mr. Joseph Williams was the Contractor that was appointed to construct the large structure known as the Selkirk Enginehouse or Roundhouse’ The building was about 90’x 180′ long with a 12′ deep stone foundation that was 2′ thick. The walls were bricked (about 18″) throughout. The ceilings were about 15′ high except in the centre where it was almost 30′ high. The roof was covered with a mica-like substance and then covered with small gravel. It had four brick wings. The high ceiling in the centre had steel beams running across it. The large windows could be opened by pulleys and there were 5 or 6 flues connected by pipes which would be used to carry off the smoke from the train engines’ The building possessed a 50′ square basement made of stone with a brick floor and sewer. Also, built were ten smaller cellars about 4′ wide by 5′ deep and 20′ long, walled and floored with bricks, which would be under the ten engines or cars that the structures could house for repairs or construction at any one time.

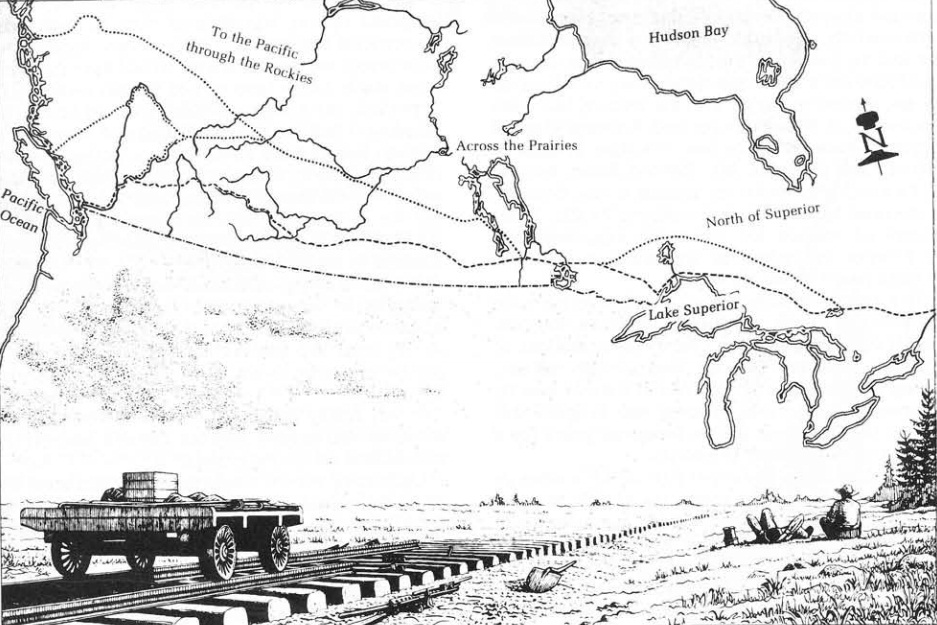

The Battle of the Routes … Each of the routes sketched below was considered for the Canadian Pacific Railway.

The building cost about $60,000 to construct and was completed by Jan. 1880. Messrs. Rowan and Schrieber inspected the enginehouse and it was turned over to the Government of Canada by the contractor, Mr. Joseph Williams on Jan. 23, 1880.

By May 12, 1880 there was three month’s supplies for the CPR in the storerooms of the enginehouse at Selkirk and Mr. Joseph Logan had just completed putting in the large turn-table which had been manufactured by Mr. Wm. Hazelhurst of St. John, New Brunswick.

Almost at the same time, the work on the 2 mile spurline track, running from just east of town to the head of the east slough, on the east bank of the Red River, where the Hudson Bay Company were erecting a large warehouse and depot for the receiving of freight and supplies, had been started. The man in charge of the spur line construction was Mr. David Douglas and he had completed the 2 miles of line in record time by July 20, 1880. It was reported to be in good condition. However, the line from the Selkirk Station to the spur switch was said to be in disgraceful condition. The “floating warehouse” of the Hudson Bay Company was to be taken to the end of the spur line upon completion of the 2 mile rail connection. Also, the Hudson Bay Company were erecting a large store at the end of the line near the floating warehouse. This Hudson Bay Company enterprise for the storage of freight and supplies and it was reported the Hudson Bay Company Store was to supply the wants of the vast numbers of immigrants expected to pass by the store on their way northwest.

Meanwhile, back on Monday, March 15, 1880 many Selkirk people had met to discuss the railway and bridge situation. James Walkley chaired the meeting with James Weidman as Secretary. The chairman briefly stated the object of the meeting and then addresses were given by Mr. E.H.G.G. Hay, MPP for St. Clements, F.W. Colcleugh of Selkirk, J.W. Sifton of Selkirk and Jas. Taylor of St. Andrews. Three motions were passed.

All of them were in favor of a bridge over the Red River “at the point determined by the government” and recommended a petition be sent to the Minister of Railways and Canals, “urging early construction of that link of the CPR westward from Selkirk to where it connects with the Winnipeg Branch” as soon as possible. This motion carried.

Then another motion moved by Mr. Hay seconded by F.W. Colcleugh “that as J. Ryan, M.P. and other members of the House of Commons dispute the opinions of the Chief Engineer and staff, as to suitableness of a location at Selkirk as a Railway Crossing, be it resolved that in the opinion of this meeting, the Engineer and Staff are correct in their views.” This motion carried, as well. The third motion was moved by Mr. Sifton, seconded by Mr. Colcleugh, that resolutions be forwarded at once to the Minister and represent our views on the matter of “Bridging the Red”, carried. The following men were to prepare the petition: Mr. E.H.G.G. Hay, James Taylor, F.W. Colcleugh, F.J. Bowles, R. Bullock, L.S. Vaughan, Joseph Monkman Sr., James Walkley, and J.W. Sifton.

Meanwhile, construction of the railway had progressed very slowly under Alexander Mackenzie (Prime Minister from 1873 to 1878) who believed the railway construction should be only as fast as government funds would allow. By 1878 as mentioned, there had been built only a short line, the Pembina Branch from Selkirk down to the American border to connect with the US railway system, a few miles of track east from Selkirk, and a few miles west from Fort William. After 3 years of construction, only 76 miles had been laid.

While a bridge across the Red to its west bank was projected at Selkirk, it had not yet been built. The Pembina branch ran down the east side of the Red River, passed through St. Boniface where a station and freight sheds were built. It was not too convenient for Winnipeg who had to have their freight and passengers carried by ferry, barge and boat across the Red River from St. Boniface to Winnipeg.

It should be mentioned that during all this railway activity, the City of Winnipeg, had not been idle. They had been very upset over the government’s decision to cross the Red River at Selkirk and follow a northerly route. The line would be passing well north of most existing settlements, and its construction was to be directed from Selkirk upon completion of the road. Selkirk, then, would be the point of entry to the west from Eastern Canada, and not Winnipeg.

The City watched in 1875 as the little town north of them really came in to existence in anticipation of its importance as a railway centre. They saw much activity and building going on in 1876 and the town had the availability of easy building material close at hand. Stores and hotels were being erected with alarming speed. Winnipeg delegations were formed to wait on the Prime Minister urging him to change the route further south to Winnipeg but he refused saying national interest took precedence over local concerns. Crossing the Red at Winnipeg would mean 30 more miles of roads and rails and besides Winnipeg was flood prone. The Winnipeg petitioners very reluctantly accepted the decision, but probably were more determined than ever to find a way to urge the route south.

As mentioned, from 1875 to 1878 only 76 miles of rails had been laid from East Selkirk east and Fort William west. Winnipeg watched the slowness with much interest. This delay was what Winnipeg needed in order to further their own interests. They organized a mass meeting in Feb. 1877 and passed a resolution calling upon the City to pay a cash subsidy of $200,000 to any company who would build a railway from the City to the Western boundary of the province.

Then in Nov. 1878 the City proposed a $300,000 bonus toward the construction of a bridge across the Red River from St. Boniface and the desired railway to the western boundary of the province. A group comprised chiefly of Winnipeg citizens accordingly organized the “Manitoba and South Western Railway Company,” to build the desired road and earn the proffered bonus.

The year 1878 had been an important turning point for Winnipegers for another reason, because, that is the year that John A. Macdonald and his conservative party were returned to office. During the election campaign, many hints had been expressed promising, if elected, they would pass the transcontinental through Winnipeg rather than Selkirk. Selkirk was not too alarmed, it was thought this would be just another unfulfilled political promise. Besides, the government was about to build a large enginehouse and other railway construction at Selkirk.

In April 1879, Macdonald had announced that the Prairie Section of the railway would be built along a more southerly route than had been projected by the Mackenzie Government. He also further stated that in so far as possible, the road would be built through existing centres of population.

That is all the City of Winnipeg needed to spur them on. In view of this development the City of Winnipeg Council unanimously approved the following resolution: “That whereas the Council having been informed that the Dominion Government intends to change the route of the Pacific Railway to the South of Lake Manitoba, and whereas the people of Winnipeg, in mass meeting assembled, have pledged the City to a vote of $300,000, if necessary toward the construction of a bridge across the 43 Red River, and western railroad extension;

Therefore, be it resolved that the Council pledge the City to pay the cost of construction of a railroad bridge across the Red River provided that the Dominion Government will construct the Canadian Pacific Railway from Winnipeg westward.”

Winnipeg delegation hastily proceeded to Ottawa to interview Sir Charles Tupper, Federal Minister of Railways and Canals, to urge this gift upon him’ Sir Charles promised the delegates that if the City built the bridge, the Government would build a branch line from Selklrk, and that a branch line out of Winnipeg would in fact be built before the main line out of Selkirk’ This occurred in May, 1879.

The City of Winnipeg Council promptly prepared a bylaw requesting permission of ratepayers for issue of debentures to finance construction of a railway bridge’ with stipulation that it be made available to the Manitoba and South Western Railway as well as a branch line to be built by the government- Even before the by-law was passed in July 1879, the federal government had called for tenders for the construction of 100 miles of railway west of Winnipeg and let out the contract in Aug’ 1879 to be completed in l2 months time.

Considerable confusion prevailed in the fall of 1879 regarding the colonization Railway because four different routes were being surveyed out of Winnipeg at the same time.

There was still no clear indication whether the line would be a branch line (as originally planned) or if it would become a part of the main line as Winnipeg wanted.

Confusion was compounded by the fact that a civil engineer had journeyed to Selkirk in May, 1879 to survey the proposed main line west of the town.

Meanwhile, a word about the Hudson Bay Company’ This Company played a key role in the struggle to draw the railway through Winnipeg. The Hudson Bay Company owned 1750 acres of land in the city by virtue of the 1869 agreement, whereby it had surrendered to Canada its claim to the western territories but had been permitted to retain blocks of land in the vicinity of its trading Post.

On Dec 8, 1879, Sanford Fleming, Engineer in Chief of the CPR recommended to the Minister of Railways that the Government not accede to Winnipeg’s request that the Government construct a railway bridge across the Red River at Winnipeg, owing to the flood prone land there.

Mr. C.J. Brydges, Land Commissioner of the Hudson Bay Company, instructed the Winnipeg Agent for the Hudson Bay Company to obtain testimony of local Hudson Safe Company employees regarding the behavior of the river. The agent produced letters from five employees, all of which testified that the Red River had not flooded in the recent past to the extent reported by other sources. Sanford Fleming had commented critically on these letters, and pointed out that, any benefit to property from the establishment of the bridge at that put.. (Winnipeg) would accrue to individuals, and mainly in. Hudson Bay Company where they have 1750 acres’ (Feb. 10,1880).

In the fall of 1879 Macdonald had led a cabinet mission to Britain to solicit more money for the railway project, but in vain.

In early 1880 the Canadian Government had commenced negotiations with the Canadian group headed by Donald R. Smith. An agreement was reached by Sept’ 1880 and formerly announced to Parliament in Dec’ 1880 as the “Canadian Pacific Railway Act,” embodying the agreement. It became law on Feb. 17, 1881′

We should mention here that when Sir Charles Tupper had visited Winnipeg in Nov. 1880, that the City of Winnipeg Council had presented a memorial to him that promised in addition to the one million dollars spent in 1829, they were willing to grant railway buildings and grounds tax free exemption for an extended number of years if they would build their workshops and depots in Winnipeg. Tupper told them at that time that it was up to the Syndicate, but he would support Winnipeg as the location.

The City Council took no chances, they hastily dispatched a delegation south to interview members of the Syndicate and urge them to locate the depot and workshops in Winnipeg. By June 1881 the CPR Company formerly offered to locate its workshops in Winnipeg. g and to build the desired railway southwest providing Winnipeg granted the Company $200,000 bonus, land for a station, and exemption of its property from civic taxation in perpetuity. By an overwhelming vote (130 to l) the local ratepayers approved (July 1881) a by-law framed along the lines demanded by the CPR’ The CPR, at once, started construction of workshops, freight shed and passenger station in the City of Winnipeg.

The people of Selkirk continued to hope that the main line would pass through their town, as originally planned’ Only a bridge and a dozen miles of road were lacking to complete the connection between Selkirk and Victoria Junctions, from which point the branch out of Winnipeg proceeded in a westerly direction. From an engineering stand point, the construction of a bridge and the short stricter of track was an obvious requirement, since they were links in the most direct route from east to west, with a crossing of the Red River, that would be immune from flooding, etc., etc. It would appear that Selkirk had not kept up with all the changes that were transpiring south of them.

Then a CPR representative informed the people of Selkirk that the company did not consider it necessary to build a line from Selkirk to Stonewall (an integral link in the originally-planned main line). However, if the local municipality would provide a bonus of $125,000 the CPR would end an engineer to locate a bridge over the Red River al Selkirk, together with the connection to Stonewall. If they failed to do this, the CPR would straighten out the line from Whitemouth to Winnipeg leaving Selkirk off the main line altogether. The money Was never raise. In the latter part of 1881 the CPR with the consent of the federal government built a new line directly from Winnipeg to Portage la Prairie shortening the rail distance by about 17 miles. A private group was organized in 1882 to build a railway from Selkirk to poplar Point, there to effect a junction with the line out of Winnipeg but the attempt came to naught. Winnipeg’s economic and political strength had proven superior to Selkirk’s nautical advantages. The threat to leave Selkirk off the main line altogether did indeed occur, but at a later date.

To recap at this point, the final decision to build the railway through Winnipeg and not Selkirk was not the result of a logical consideration of the merits of the two locations. Rather, the greater resources of Winnipeg, the fully established centre, were brought to bear. In 1881 Winnipeg made concessions, as mentioned, to the CPR interests in the form of $200,000 bonus, a free right of way worth about $20,000 and exemption from taxation in perpetuity of CPR holdings within the City, and the building of a $250,000 bridge over the Red River. In return, Winnipeg was guaranteed not only a position on the main line, but also that the CPR maintenance shops for its western operation would be located there.

Selkirk to the north had remained a potential rival until the CPR had demanded $125,000 for the building of a bridge at Selkirk and the construction of a connection to the main line west of Selkirk and east. The alternative, the CPR representative told Selkirk, was the straightening of the route east of Red River so that the mainline would pass exclusively through Winnipeg. The CPR official waited a period of time, knowing Sanford Fleming’s arguments were valid as to the desirability and geographic location making Selkirk a genuine choice — Winnipeg at this point was doubtful from being flood prone — but Selkirk failed to raise the bonus and meet the railway demands, and at this point, ceased to present any serious competition to the organized agreements formed in Winnipeg.

One item during research which I found most interesting was that the contractors in Winnipeg had been out to Selkirk and obtained permission from the Government to quarry stone on the eastern town plot. By Selkirk Quarry. This was the same stone that had built the large Selkirk Roundhouse (Engine house) for the railroad under the Government of Canada Public Works contract. There was also mention of lime also being shipped in large quantities from Selkirk to be used in Winnipeg for the mason work on the bridge. By July, stone was being rushed out of the quarry at the rate of 30 yards per day for the Louise Bridge.

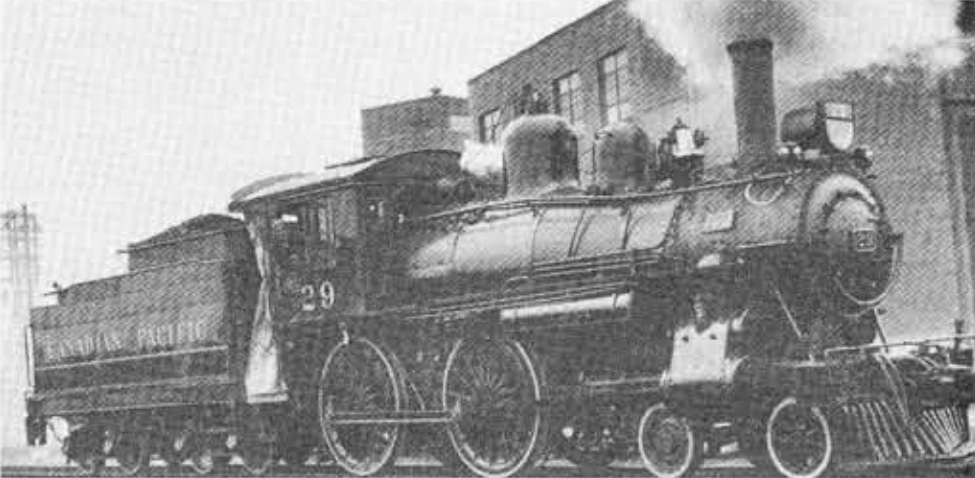

By Feb. 1881 the government allowed the creation of the CPR and transferred all railway lines built by the government to the new private company. By the fall of 1881 William C. Van Horne was on the payroll of the new company and looking over the line north and west of Superior, the old Precambrian country. It is stated he was military like in his speech and decisions, ruthless and single-minded in any cause he served, and he was out to complete a railroad with a deadline to meet. He was paid $15,000 a year and started work in earnest in 1882. They say the gentleman enjoyed a good challenge and Van Horne had reason to be impressed, he had a new railway to build, the longest in the world. The CPR turned the first prairie sod in 1881 and by June 1882 Van Horne had launched his record-breaking push across the prairies, and had completed the rail crossing at Winnipeg over the Red River with the completion of the Louise Bridge.

Winnipeg in the spring of 1882 was turned into a giant railway depot. Van Horne contractors needed 3000 men and 4000 horses and they needed provisions and food for 7600 men. The floods came in April 1882, and in May they were hit by blizzards. The line from St. Boniface to East Selkirk going east finally met up with the line coming west from the Take head at Rat Portage. The rails between Rat Portage and Port Arthur were actually connected on June 19, 1882, making, in theory, a through line of railway between the Lake head and Winnipeg. However, more than a year was to elapse before problems of alignment and leveling, particularly over the muskegs and the many bodies of water, were overcome sufficiently to allow the passage of trains with reasonable dependability.

This was the area of the infamous contracts 4l and 42, which later would form the subject of a Royal Commission of Enquiry.

With the work on the CPR built section east from the Lake head scheduled to begin in the spring of 1883, it was imperative that the Canadian Pacific Company should have control of the whole Lake head to Winnipeg track by that time. Ultimately, the line in an incomplete state was placed in Canadian Pacific’s custody by May, 1883. The eastern limit at Lake Superior was considered the eastern extremity of the Western Division.

This Thunder Bay line was different than those areas west ;f the Red River, in fact, different from probably any other rail line. Private individuals living along the line had been in the habit for quite some time of using their own handcars and velocipedes to travel along back and forth over the lines at their will’ This practice had been tolerated by the various contractors because most of the people concerned were employed in the actual Construction or else in some related trade of supplying the workers or contractors. Once the CPR scheduled operations were started, this unauthorized traffic would have been to be stopped, as it was a menace to regular trains.

Besides the problem of unscheduled use of rails by merchants, lab our foremen and supply teams, we also had land that wouldn’t take kindly to track laying’ In some of the more serious muskegs, the embankment had to be laid on a “Mattress” of tree trunks, roots and branches. It was some time before roadbeds laid in this way were stabilized. It is said that, at one location’ seven complete sets of tracks disappeared into the muskeg. There are many recorded instances where the track disappeared below the surface of the water after the Passage of each train, necessitating more ballast to bring The rails’ above the water again’ In some cases, it was necessary to repeat this procedure for weeks before the embankment became firm.

Alcohol was also a great social problem during the building of the railroad. Those who did not use it themselves, often catered to those who did’ Mr. John M. Egan was appointed General Supt’ of the West Division and took over the contract to build the CPR starting in Jan. 1882. His appointment terminated on Sept. l, 1886 and he was replaced by William Whyte at that time.

Work stoppage of 3,500 men (locomotive and firemen) started on p”..Dec 11, 1883 when they refused to work in Thunder Bay to Calgary. Work was halted on the completed portions. The hardest hit was the partially operated service from Thunder Bay on’ Cause of the disruption was the company’s attempt to reduce engineers’ salaries by $6 per month. So the Engineers when on a strike and the firemen went off to work in sympathy.

The strike only lasted for 8 days. The CPR’s attempt to reduce wages stemmed from a financial dilemma and near bankruptcy. Construction costs during the summer of 1883 had drained the company’s capital’ At the beginning of Dec. 1883 the CPR stock had reached its lowest ebb and 1883 proved to be a year of recession in the Canadian Northwest.

The strikers complaints (besides reduction of wages) were basically the high cost of meals and poor sleeping quarters at divisional points, overcrowded and sometimes they had to sleep in the engines. The meals cost 75 cents each and at 2 meals per day, this meant $1.50 to eat and they only made $3.50 per day. Long working hours sometimes totaled about 51 1/2 days at 12 hours per day just to make from about $135 to $204. Another worker could work 26 days at 12 hours per day just to produce $95 per month. The men complained that any wage reductions was unacceptable. A wage increase with reduced working hours would be more to their liking. The Strike, while it lasted, was bitter. The engineers from the Lake head cabled Headquarters in Winnipeg that men were indignant about railway action and could hold the fort, “till the grass grows green.”

However Van Horne wired Egan that he had recruited replacements for the strikers from Chicago and they arrived on Dec. 18, 1883 and the document officially ending the strike was signed on Dec. 19, 1883. However, the railway and craft unions continued to organize and strike during the next year.

By Feb. 1884, the CPR received a government loan of some $22,500,000.

To the Indians and Metes of the Red River and Northwest Territories, the railroad became the symbol of the end of the good old days. Another resistance was forming in the northwest and open rebellion broke out in 1885. Louis Riel, who had gone into exile after the 1869/70 resistance, had come out of exile in the US to set up two more provisional governments for Saskatchewan and Alberta. Only this time it was called Treason, because Canada was an organized nation.

Meanwhile, financial problems reached a peak for the CPR in Feb. 1885 and to compound it, B.C. was passing an anti-Chinese immigration bill, which affected the lab our force of the railway. By March, 1885 the BC authorities stopped all landed Chinese immigrants. Riots in the railway camps became common due to no pay for the workers, strikes occurred and the NWMP were called in. However, the NWMP couldn’t spare many men because most of them had been attending the North West Rebellion.

Van Horne took advantage of the situation and promised the government he could get troops, arms and provisions over the route to the rebellion area. This was quite a promise considering there were still four unfinished sections and 86 miles yet to complete. However, he did it, he transported 8000 troops by rail to the scene of the conflict and it was soon over.

The rails linking east with west was met and linked on Eagle Pass at a site called “Craigellachie”. The last spike was driven by Donald A. Smith on Nov. 8, 1885 with Sanford Fleming, Van Horne and Major Rogers and John Egan in close attendance. Nine days after the last spike was driven, Louis Riel was hanged in Regina.

AT EAST SELKIRK

The first through passenger train of the new CPR left Montreal for the Pacific on June 28, 1886 and arrived in Winnipeg crossing the Louise Bridge on July l, 1886 and arrived at the BC Terminal at one minute to noon hour on July 4, 1886 heading for the Pacific.

The dream for a transcontinental railroad was finally realized, 15 years after it was approved to commence and 23 years after Sanford Fleming had placed his plans on paper. Sanford Fleming’s prediction of 25 years was not far off the mark.

The completion of the CPR spurred settlement all along its lines and the big move from eastern Canada was really on. Thereafter, people came from eastern Canada, the United States, Great Britain and Central and Eastern Europe to settle in the west.

To recap the East Selkirk/CPR connection. It was decided to cross the Red River at Selkirk in 1871, the town was mapped out by 1875176 and construction under way. The Railway bridge across Cooks Creek was built in 1878 and the Roundhouse was constructed in 1878/79 and handed over to the government in Jan. 1880. The railway reached East Selkirk in Dec. 1877 but was delayed until Cooks Creek Bridge was completed in 1878. During 1880 the railroad was using the roundhouse as a supply depot and after May when the turntable was installed, was an engine repair depot. Also in May 1880, the 2 mile spur line was being constructed to Colville Landing at the east slough, and was completed by mid July 1880. The Hudson Bay Company “floating warehouse” was placed at Colville by 1880. Also in 1880, East Selkirk was shipping large quantities of stone and lime for the building of the Louise Bridge in Winnipeg.

Between 1878 and 1881 the government worked the railway building and in Feb. 1881 the CPR were incorporated and the government built lines were transferred to the new CPR on May l, 1881. This included the section from St. Boniface, through East Selkirk to Telford near the Ontario/Manitoba boundary. This line eventually met up with the line coming west from the Lake head in 1882.

In May 1881 the large Hudson Bay Company store at Colville was almost completed and Colville Landing was booming during the next few navigation seasons and by 1883/84 was all but abandoned. The spur line track heading to Colville was removed prior to the summer of 1887.

In 1883 all the brickyards save one were operating, the quarries were running and the roundhouse was building and repairing cars. That was when the Town of Selkirk on the west bank, incorporated in 1882, started to systematically entice business over to the west side from the east bank. The Northwest Lumbering Company and others were moved over during 1883 and buildings skidded during 1884.

By 1898 when the conversion of the Roundhouse was commenced to convert same to an Immigration Shed, East Selkirk was almost a ghost town. Things hummed only a bit during the immigration hall days from 1898 until it was closed up in 1907.

The threat by the CPR to leave Selkirk off the main line altogether was realized in 1907 when the CPR built a new section from Molson to Winnipeg thereby shortening the main line route by 10 miles’ Henceforth all transcontinental traffic moved over the new section, and the original line to Selkirk and thence east was used only for local traffic.

The CPR Station which was completely remodeled and renovated in late 1905 was removed about I 12mile east of the old site by the end of 1906.

Meanwhile, the railway branch running on the west side of the river from Winnipeg to the Town of Selkirk was constructed by the CPR and was opened for service at the end of the year 1883. It was extended to Winnipeg Beach in 1903, Gamily in 1906 and Riverton in 1914.

In conclusion, it would appear that Winnipeg was not the only interest working against East Selkirk becoming the main railway centre for the east-west traffic’ Much of the blame lies much closer to home. However, much of the documentation to substantiate certain statements in this relation are not yet placed in proper chronological order. Therefore, we end the story here, for time does not allow us to properly interpret the research gathered.

We hope you enjoy the photographs that have been gathered depicting early CPR days. Many of the views were shot by Mrs. Smiley who was the daughter of a railroad man. Besides being an amateur photographer, she also had her own “dark-room” and did her own developing. Her hobby allows us the privilege of retaining early scenes of East Selkirk that otherwise might have been lost. Her son, Jake Smiley, submitted her album for your enjoyment.