Among the earliest and most vivid of my childhood recollections are those of my father’s old watermill. And, while this ancient and primitive institution was by no means unique among its fellows, nor the first of its kind in the Red River settlement, I think it sufficiently typical and the facts connected with its construction and operation sufficiently interesting to warrant my setting down a few of them here, for the benefit of those “moderns” who were not privileged, like a few of the rest of us, to live through such scenes of “history in the making. ”

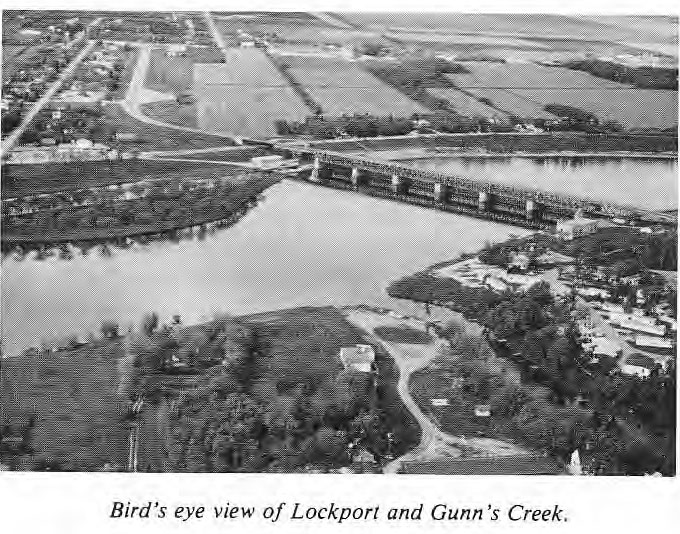

This primitive but ambitious enterprise was conceived and carried out in the early 1850’s. My father was then a young man, newly married, and possessed of little of this world’s goods save an abundance of health and strength, unconquerable optimism and the will to succeed. He had no monied capital; but, some time prior to this, his father, Donald Gunn, the historian, had deeded over to him his original homestead, lot 163, Parish of St. Andrew’s, on the east side of the Red River, where the big traffic bridge over the St. Andrew’s lock and dam now is; and on this farm was a creek — or rather, a small part of one — still known locally as “Gunn’s Creek.” This little stream, now kept at a uniform summer level by the backwater of the Lockport dam, today forms a picturesque beauty spot well known to travellers approaching the St. Andrew’s lock from Winnipeg by the Henderson highway.

Winding sleepily in and out through beautiful groves of oak and elm, and always still as a mirror, it has little to suggest to the casual observer, of the bustle of industry or the stirring activities of commercial enterprise. But sixty years ago, it presented a very different aspect. In those days, before our ubiquitous drainage system had despoiled the marshes of their moisture and desiccated the fair face of Mother Earth, Gunn’s Creek was accustomed to go on periodic rampages that attracted the attention of even the dullest observer. Taking its rise in those deep and extensive morasses that form the drainage basin of the hill country to the east and south, it galloped down its tortuous, pebbly channel, in the spring of the year or during rainy seasons, like a veritable young ,,Kicking Horse” — a phenomenon not long lost upon the new proprietor of the Gunn homestead,

DECIDING TO USE POWER

Here was water power-limited and intermittent, it is true, but sufficient for the purpose. And there was wheat to be ground. being produced in ever increasing quantities in the neighborhood. What more logical, in the premises, than a watermill? So a watermill it was to be. And a watermill it was.

This watermill, however, was not built on the original homestead. A suitable site was purchased a little farther down the stream (on Lot 167), not far from its junction with the Red River, and on this spot building operations were soon under way.

The “log” of the actual building of this old mill would be too long to give here; although I have it, in brief and fragmentary form, in the original account book kept by my father at the time. Many names figure in the record of men now long gone to their rest. They were all men of the neighborhood, all equally “to fortune and to fame unknown”, and blissfully innocent of the seductive blandishments of the “walking delegate”. Their wages, for the unabbreviated days of labor unrelieved by modern machinery that they contributed to if. construction, ranged from 25 cents a day, for the ordinary laborer, to 45 cents or 50 cents a day for the skilled artizan, their food, presumably, being furnished in addition. “A starvation wage”, according to the sophisticated “living wage” standard of today.

WORK DURING THE SUMMER

The work of constructing the dam and building of house the machinery was carried on principally during the summer, this being the most convenient reason. During the later summer it was especially convenient to work at the dam, as, the spring freshness and rainy season being past, the bed of the creek became quite dry, thus doing away with the difficulties attendant upon the harnessing of a living stream. The dam was first constructed as a wall, or dyke, of limestone, a plentiful supply of which was quarried from the adjacent river bank; this being subsequently reinforced by a heavy, sloped bank of clay, well packed in on either side. This dam was pierced, at equal intervals along its length, by three spillways about five feet wide, constructed of heavy oak posts and planking, and controlled by strong oaken gates, with oaken levers for raising and lowering them. These levers were just a stout oak sapling from the woods, about the size of an ordinary fence post, passed over a raised beam across the top of the spillway a few feet back; the business end of it being securely fastened to the top of the gate by shaganappi thongs passed through an auger hole in the framework, the handle-end of it being easily manipulated from the top of the dam in the rear. The lever controlling the “grinding gate” was an exception to this, being passed forward through the end wall of the building, thus providing for the control of the power from within the mill.

The mill building itself was of log-frame construction, about 24 by 34 feet, and two storey high, the floor of the second storey being just above the level of the top of the dam, behind the most northerly end of which the building stood. A gap of some six or eight feet between the front of this building and the sustaining wall of the dam was bridged by a planked approach to the main entrance of the mill, which was in the second storey, about midway of its length. ln this second storey were the stones that ground the flour, the sundry bins for the storage of wheat, all grist being received into the mill over the planked bridge aforesaid. In the lower storey were housed the bolting machinery and the great spindles and wheels that distributed the power to the various working parts. Here the finished product was bagged and delivered to its waiting claimants through a poster door in the north end of the building.

NO GLAZED WINDOWS

The mill building was quite innocent of glazed windows, sufficient light for operation by day being admitted through the open door and a couple of small square apertures in the centre of the south gable. When necessary to grind at night, some sort of fish-oil lamps, suspended at convenient points, were used. By day, also considerable light was admitted between the unchinked Logs; for, from very shortly after its completion to the day of its final demolition, the building remained quite destitute of the chinking and plaster that usually form the finishing touches to structures of this kind. The roof, of course, was of thatch, which was always kept in repair with difficulty, for the same reason that the walls went unchinked — a reason that will appear later.

It may be truly said, that this old mill was “fearfully” and wonderfully made. Nearly all the machinery housed in the structure above described was, a year or so prior to the first turning on of the water, growing in the forest or reposing peacefully in its native habitat in the ages old strata of the earth. With the exception of a few small metal gear wheels, brought by Mississippi Steamer and Red River Cart from St. Louis, Missouri and some brass bolting cloth from England, every wheel and spindle and every other working part, was manufactured from local materials by local artizans. Al1 the wheels in it, with the exception already mentioned, were constructed out of native oak from adjacent woods. These were made in the seclusion of his workshop, during the winter, by my father, who, though self-taught, was a skilled wheelwright and joiner.

MARVELS OF MACHINERY

I can well remember the marvels of these ponderous and skillfully constructed wheels. The largest was, of course, the great water wheel that furnished power. This must have been, at least, l6 feet across, with three-foot face. It was built entirely of native oak, with the exception of the buckets which were of fir or some similar wood. The spindle that it turned, on which it was built, was a great oaken timber l4 inches in diameter. On the other end of this protruding into the lower storey of the mill, was the largest of several wooden gears, similarly constructed.

This one, if my memory serves me rightly, was about six feet across, and into it was geared a succession of others, of similar material and construction, which finally connected with the imported metal wheels above mentioned. These great oaken gears, were, as has already been said, marvels of the wheelwright and joiner’s art. They were built up of thoroughly seasoned native oak; the jointing of the great spokes and felloes being so perfect as to almost defy detection. Every cog of these wheels was made and mortised in separately. And some idea maybe had of the strength and accuracy of construction when, it is said, that at the time of the final dismantling of the mill, after twenty years of continuous use, they showed but little trace of wear or deterioration.

The bolting apparatus, with its revolving brushes and other parts, was also made in its entirety in my father’s workshop; as were also the hoppers and casings housing and stones; and the lumber for all these things, and for that matter, every other thing about the mill where lumber was needed, being whipsawed out of trees felled in the vicinity.

The mill was equipped with two run of stones – also of purely native material and manufacture. These were ponderous affairs, five feet in diameter and eight inches thick. They were chiseled out of the native granite on the east side of Lake Winnipeg, opposite Grindstone Point, and transported by York Boat to the site of the mill; the pattern on the grinding surfaces and other finishing touches being put on by local stone cutters there.

PLASTER SHAKEN LOOSE

Only one pair, however, of these giant stones was ever run at a time after the first experiment of trying to run them both simultaneously. Upon this occasion, as I have often heard ii told, it was as if a young earthquake had broken loose. The plaster and chinking of the log walls came down in showers and the entire plant was threatened with destruction. Needless to say, the expedient was never repeated, Nor was any attempt ever made to replace the plaster and chinking; it being found that the continuous vibration of the machinery with only one set of the stones running – made possible to make them stay put.

The task of installing the machinery and of giving the finishing touches to the various parts of this ingeniously constructed flour manufacturing plant was carried out during the winter so that by the end of March it was ready for the water. At least that was the fond belief indulged by its builder. But the water came a little sooner, and in much greater volume than was anticipated. The winter’s snow had been exceptionally heavy; and, early in April, a sudden thaw set in, accompanied by rain, which precipitated the accumulated water into its natural channels with unprecedented dispatch and violence. it came down Gunn’s Creek with a roar of triumphant freedom that was not to be lightly checked; and, when it reached the newly constructed dam, there were things doing.

At this time there was only one spillway provided for the passage of the surplus water, the inadaquacy of which for this purpose was very soon apparent. Weak points and undetected crevices, too, were soon sought out by the insidious and insistent element; so that, between what was threatening to go over and what was threatening to go through or under, it soon began to look as if the whole dam, mill and all, would be carried into the Red River. Ln such a crisis, immediate emergency measures had to be taken to save the situation.

RECRUIT VOLUNTEER HELPERS

Gangs of men with barrows and shovels were quickly mustered and put to work, some wrestling with the leaks in the dam, others cutting a ditch around it to let the surplus water away. lt was a strenuous days battle extending far into the night; but when morning dawned the situation had been mastered and the mill saved.

An additional spillway was afterwards put in, thus effectually guarding against any similar menace in the future. Despite such early aberrations, however, the mill proved to be unqualified success. Having “sowed its wild oats” and demonstrated its frolicsome moods in a number of such escapades it settled down to the serious business of producing “the staff of life” for all and sundry who might bring their grist to its hoppers. I am not prepared to pronounce any judgment on the quality of the flour produced, although I consumed my good share of it. According to the uncritical standards of the time, however, it was considered good frozen wheat and bin-heating misadventures, of course, being allowed for. The quality suffered too, sometimes no doubt, through the inexperience of the miller.

I have often heard if said, for example, that all the flour turned out for a considerable time at the beginning of its operation, was produced with the stones running backwards. I don’t remember whether this original output was labelled “New Process” or not. But I don’t remember anyone dying of “flour barrel consumption” or any gastric malady through its use so that it could for have been too bad, even at that. At any rate, there was soon no lack of grists. They came in squeaking Red River carts, in skiffs in dugouts and York boats, from all over the Settlement. They were there from the hand-to-mouth yokel of the neighborhood with a single bag on his back, to the York boat brigades of the Hudson Bay Company with hundreds of bushels.

ln fact, in the palmy days of this old mill, it was more often the water than the grists that was lacking. In the spring of the year it came down in floods, as described above; and grinding had to be kept up by night as well as by day, in order to get the waiting grists ground, and not to lose any of the available power of its precious volume. In a dry time the grists accumulated and waited on the miller; the miller waited on the capricious favor of the “weather man”. My father had a stake driven in one edge of the dam, near the shore, in the top part of which were sawed notches to measure height of the water-this primitive water-guage being known among us as “the sawed stake” and I can well remember being sent by him, on various occasions, to consult this “sawed stake” oracle, in order to acquaint him with the level of the water; the difference of an inch more or less, registered by those fate full notches, always determining the momentous question, “to grind or not to grind?” ln a period of stubborn drought, with no Elijah to intervene, the only recourse for the flour-hungry householder was a resort once more to the “querns” or the “beating block”, an alternative that not infrequently presented itself.

From a financial point of view, while not producing dividends comparable to those of our great flouring mills of the present day, I would judge that the venture was fairly satisfactory to its enterprising proprietor. Ordinarily, the system of payment was by moulter this instance, pronounced “mooter” that is, a certain percentage of each bushel of wheat was taken by the miller as his remuneration for grinding the balance. I very clearly remember the old “mooter measure”. lt was a miniature wooden tub made with staves. one of which was left standing a few inches above the others to form a hand-hold. It would probably hold about a gallon. Pound notes and gold sovereigns were also considerably in evidence; such patrons as the Hudson’s Bay Company and other wealthier residents of the community probably preferring to pay in those media. Upon the introduction into the country, however, of steam flouring mills, with improved machinery and methods, the patronage of the “old mill” naturally well off, making its continued operation unprofitable. It was accordingly closed down, and a number of years later, dismantled.

by George Henry Gunn