In 1878 and 1879, the Government of Canada built the East Selkirk Roundhouse in anticipation of the coming Canadian Pacific Railway. Sanford Fleming, a surveyor for the CPR, had selected the East Selkirk/Selkirk site for the railway to cross the Red River. This area had high ground and was not susceptible to flooding like the Winnipeg location. Many trains were expected to travel through the area and the roundhouse, or engine-house, would make any necessary changes or repairs on the train’s engine. Fate though, had other plans.

To begin work on the proposed Roundhouse project, the government hired numerous contractors. The massive building of stone and brick was located south of the present day corner of Colville Road and Frank Street. Most of the stone came from the East Selkirk Quarry, located north of Frank Street. The bricks needed for the building came from the East Selkirk brick plant, located west of Cook’s Creek. With four brick wings and a basement, the final dimensions of the building measured 90 feet wide by 180 feet long. The stone foundation was 12 feet deep and 2 feet thick and the roof was 15 feet high in most areas, reaching as high as 30 feet in the roundabout area at the center. Mr. Hazlehurst of St. John, New Brunswick manufactured the turntable and Mr. Joseph Logan was in charge of its installation. The pivot in the middle of this turntable was designed to support the weight of the table plus the weight of an entire train engine. The total cost of the project was $60,000.00. The building had a final inspection done in 1879. The project was completed in January 1880 when the roundhouse was handed over to the government.

Selkirk residents felt a great deal of anticipation about the coming railway. Hundreds of wealthy business owners and land speculators flocked to the East Selkirk area. All of them were hoping to experience the benefits of living near a transcontinental east-west connection. However, no one expected that the rail line would be changed. In April of 1879, Canada re-elected Sir John A. MacDonald’s Conservative government. Macdonald announced that the railroad would cross the Red River at Winnipeg instead of Selkirk, where the previous government had originally intended.

The city of Winnipeg had lobbied hard to have the railroad diverted through their growing city. Winnipeg offered $300,000 to construct a bridge for the railroad to cross the Red River, if it were to pass through their city. However, because the roundhouse had already been built in East Selkirk, the local politicians and citizens did not believe that the location of the river crossing would be changed. In May 1879, the government announced that the rail line would be diverted south through Winnipeg. The government promised to build Selkirk’s railway crossing at a later date. Selkirk protested, but they did not have the funds to build a bridge across the Red River in the Selkirk area. The funds for a bridge were never raised, and eventually the railway plans for the Selkirk area were forgotten.

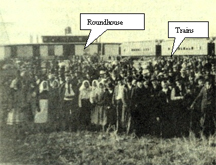

Eventually many families that had settled in East Selkirk moved south towards Winnipeg. As a result, the roundhouse and many homesteads were deserted. Sadly, this roundhouse would never house a train engine. After a few years, some people wondered if there might be other possible uses for the roundhouse.W. McCreary was the Commissioner of Immigration in Winnipeg and in the late fall of 1898, he found another use for the roundhouse; his idea was to turn the roundhouse into an immigration shed. This building would provide temporary housing for the influx of new immigrants coming from Europe. He corresponded with the Deputy Minister of the Interior who was responsible for immigration. He stated, “There is an old roundhouse at East Selkirk that I intend looking up, which might hold 500 to 1000 of them (Doukhobor immigrants) if it could be put into shape.” At this time there were many immigrants arriving from Western Europe. Space was limited in the major cities, such as Winnipeg, and the Selkirk area was still on the main rail line of the CPR. Because of these reasons, the government was eager to make the building operational to help house some of these destitute immigrants.

Mr. McCreary and his associate, Dr. Patterson, thoroughly investigated the building. It was considered ideal because little repair work was needed. It had sufficient space and window ventilation; another benefit was that, in case of disease, a doctor lived in a nearby village. The only difficulty was the concerns from the citizens of Selkirk about what type of people this shed would bring into their community. Regardless of their unease, plans continued and suggestions were then made to add a second floor for the children, cooking facilities, and sanitary necessities. It cost a total of $2,000 to renovate the roundhouse. It was now estimated that the old roundhouse could accommodate 1500-2000 immigrants. The East Selkirk Immigration shed officially became operational in 1899.The first wave of immigration involved approximately 1700 Doukhobors. They were members of a Russian Christian movement, which started in the 18th century. They were fleeing persecution for their views, which included rejection of ecclesiastical and state authority. This shed became their temporary home. Here they felt comforted to be living with others around them who were in the same situation. They then applied for land through the Homestead Act:

Mr. McCreary and his associate, Dr. Patterson, thoroughly investigated the building. It was considered ideal because little repair work was needed. It had sufficient space and window ventilation; another benefit was that, in case of disease, a doctor lived in a nearby village. The only difficulty was the concerns from the citizens of Selkirk about what type of people this shed would bring into their community. Regardless of their unease, plans continued and suggestions were then made to add a second floor for the children, cooking facilities, and sanitary necessities. It cost a total of $2,000 to renovate the roundhouse. It was now estimated that the old roundhouse could accommodate 1500-2000 immigrants. The East Selkirk Immigration shed officially became operational in 1899.The first wave of immigration involved approximately 1700 Doukhobors. They were members of a Russian Christian movement, which started in the 18th century. They were fleeing persecution for their views, which included rejection of ecclesiastical and state authority. This shed became their temporary home. Here they felt comforted to be living with others around them who were in the same situation. They then applied for land through the Homestead Act:

Also known as the Dominion Lands Act in Canada, it was passed in 1872. This act was based upon the American Homestead Act to encourage immigrants to settle in the prairies. It granted 160 acres of land for a fee of $10.00. Anyone over the age of 21 or the head of the family could apply for a quarter section. Settlers had to agree to live on their homesteads for a minimum three-year period, clearing and farming the land. They also had the option to purchase an extra quarter section next to theirs as a pre-emption by paying the market price of the time, which was about $2.00/acre. The measurements for a quarter section were 160 acres = Quarter Section = Homestead = 1/2 mile x 1/2 mile.

The large number of farms and homes, which were abandoned when the railroad moved to Winnipeg, offered many possibilities for future homesteads. Over the years, immigrants of many nationalities arrived. The Galicians, originally coming from the area which is the present day province of Galicia, Ukraine, were one of the largest groups to come. Their homeland was simultaneously under the rule of Austria-Hungary, Poland, and Russia in the late 18th and 19th century and was a highly oppressed area. Six hundred Galicians arrived soon after the Doukhobors and thousands more immigrants from Russia and Galicia followed over the next few years.The immigration shed at East Selkirk helped establish many immigrants in the Selkirk Interlake region. It also provided an opportunity for others to travel on to other western parts of Canada.

In 1906, after many years, the immigration shed was in need of great repair. The government decided that it was no longer an efficient investment. They sold the land around the shed to the local farmers. The East Selkirk Immigration Shed then closed its doors yet again. The building itself was still under owned by the CPR company, who rented it out to the public for $5.00 a day.

In the following years, the shed was well used. It acted as a dance hall, recreation hall, school, church, a general meeting place, and most famously, as a skating rink. East Selkirk residents were proud to say that they had an indoor skating rink. By 1916, the building was in such a state of disrepair, that it had to be demolished. Some of the materials and stones from the building were used for building the first two-story Happy Thought School stone building on old Henderson highway.

Article written by Jared Laberge St. Clements Heritage Advisory Committee – 07/14/05

St. Clements Historical Committee. East Side Of The Red. Winnipeg: Inter-Collegiate Press, 1984.