Timeline: About 8000 Years Ago: Lake Agassiz

A huge body of water covered the lands of St. Clements about 8000 years ago. Scientists suggest it formed about 14,000 years ago from the melting of a continental ice sheet. When the glacial lake drained, its sediments formed the rich farmland of the Red River valley and left behind Lake Winnipeg, Lake Winnipegosis, and Lake Manitoba.

In 1879, scientists called the great lake, Lake Agassiz – after Louis Agassiz, the first person to recognize that glacial action formed the lake. At its height, the lake covered 440,000 square kilometres, larger than any lake in the world.

What is Archaeology?

Archaeology is the study of ancient cultures. Archaeologists are the people who study ancient cultures. Archaeologists excavate and analyze physical remains contained in the layers of soil set by natural processes. Each layer of soil contains artifacts that belong to the people who occupied the site at that time. Layers of soil also hold clues to environmental conditions and changes over time.The First Peoples of St. Clements

Archaeology tells us that after Lake Agassiz receded people and animals began to migrate to the region of Lockport and surrounding areas. Archaeologists have uncovered animal bones and stone tools dating back 3000 years ago. Those early residents followed migrating animals, birds, and fish to the region in certain seasons.

Why did they choose the Lockport area?

Some reasons include:

- They came from other regions that no longer supplied their needs

- They followed herds of bison or other large game to the region

- The landscape and environment supplied their needs

- The fast flowing water at Lockport, below a set of rapids, was ideal for fishing

- The bedrock near the rapids supplied stone for making tools

- Growing corn or other crops was possible in the fertile soil (Lockport has the oldest evidence of pre-European farming in Manitoba)

Based on archaeology done near Lockport, remains from four distinct prehistoric cultures have been discovered in the region.

Larter Culture

Archaeologists refer to the first prehistoric culture as Larter Culture.

- Radiocarbon dating shows the people of Larter Culture lived in the region from between 1000 B.C to 200 B.C.

- This is a period in time called the late archaic or late middle prehistoric period.1

- One of the first discoveries of this culture happened in 1951 at a site 7 kilometres south of Lockport (Parkdale, Manitoba) near Larter’s golf course, hence the name.2

- The culture used a distinctive barbed projectile point that archaeologists termed, Larter Tanged. It has been uncovered in various sites throughout Manitoba.3

The people of Larter culture were nomadic travellers of the Great Plains (grasslands). Bison (buffalo) bones are prominent in their ancient campsites, but various kinds of fish bones and the pits of wild plants are also common. Archaeologists suggest those early hunters worked in groups to drive bison herds over a high riverbank where they would fall and be easily killed using an atlatl (spear).

“The majority of artifacts found are made of stone.”

Importance of Bison

Larter people used all parts of the bison:

- Its outer coat was used for clothing, rugs, and tent coverings

- Its bones were made into tools, utensils, and perhaps weapons

- Its internal organs were dried and made into containers to carry water

The meat from one bison fed a large group of people and it was prepared in a few different ways:

- Smoking – thin slices of meat hung over a drying rack near a fire under the sun until it cured.

- Roasting – pieces of meat was speared with a stick and held over a fire

- Baking – meat was placed on top of smoldering embers in the earth then covered with damp grass.

- Boiling – The ancients used the stomach lining of the bison to waterproof a hole in the earth and poured water in the hole. They heated stones in a nearby fire, and when the stones became hot, the people placed the stones into the water, and then added the meat to the water to cook it.

Larter Artifacts

To date no ceramics, birch bark canoes, or bow/arrows have been uncovered in Larter Culture sites. The majority of artifacts found are made of stone. According to Manitoba Historic Resources, artifacts include:

- the distinctive corner-notch dart points (distinctive barbed projectile point)

- knives

- scraping tools and punches for the preparation of leather items

- gravers for incising wood and bone, chisels, and hammer stones

Artifacts related to Larter culture have been uncovered across the Great Plains from Alberta to the Ontario/Manitoba border. All traces of them vanished at about 200 B.C.

Larter Culture people:- were nomadic travelers

- were hunters & gathers

- were stone tool makers

- used animal bones for tools, utensils, and weapons

- used bison fur for rugs, blankets, tent coverings, clothing

- used bison sinew for sewing

- used bison dung for fires

- used atlatl – spear throwers

Laurel Culture

Archaeological evidence shows that after the Larter Culture vanished, people of a new culture took up residency in the St. Clements region. Archeologists call them Laurel Culture.

- The people arrived in the region from between 200 B.C. and 1000 A. D.

- Referred to as a middle woodland ceramic-ware culture

- Archaeologists call the culture Laurel because some of the first artifacts that were uncovered from this culture came from a northern Minnesota (USA) town near the Ontario border named Laurel.

- Laurel Culture technology was different to Larter Culture, suggesting they were new peoples relocating to the region.

- Archaeologists think the people of Laurel Culture came from the shores of the Great Lakes.

Diet

The Laurel Culture did not depend as much on the bison as Larter peoples did. Their diet was a mixture of moose, caribou, deer, elk, snowshoe hare, woodchuck, beaver, muskrat, porcupine, marten, fisher and otter. They also ate loon, swan, duck, turtle, passenger pigeon, goose, and several types of fish.

People of Laurel Culture depended on the rivers, lakes, and forests for their food and resources. Some sites still hold hazelnuts and chokecherry pits, suggesting a variety of plants and berries in addition to meat in their diet. They also ate wild rice.

Tool Technology

Tool technology of Laurel Culture is different to Larter Culture although both cultures used similar kinds of stone tools. In early Laurel times, dart tips became smaller and a transition from atlatl to bow and arrow is evident. Bone, antlers, teeth, claws, and shells served as both tools and personal decoration for Laurel peoples. They also used native copper for beads, pendants, chisels, fishhooks, and knives. Some tools such as grinders suggest Laurel peoples were grinding seed and other vegetal matter into flour.

Pottery

Pottery appears during the time of Laurel Culture. Pottery is usually a sign of less nomadic travel because clay pots were bulky and not easy to carry. Their pottery was “coconut-shaped” with either vertical or slightly flared rimes decorated with various motifs pushed, stamped, or scratched into the clay before it hardened.4Housing

The Laurel Culture made oval shaped houses from tree saplings. They drove the ends of the young trees into the ground and tied the tops together before covering them with animal skins tree bark, or long grasses.

Burial

They were a spiritual culture, burying their people in mounds with personal possessions to aid the spirit in the afterlife, or the life they believed the sprit would transcend too.

Some archaeological theories suggest these ancient peoples migrated westward from their eastern homelands because of their dependency on wild rice. They travelled along the waters of western Ontario and eastern Manitoba camping along the shores where wild rice was abundant. The availability of wild rice so far into the interior may have been a major factor in the decision to build seasonal camps in the region.

Some groups reached Red River from the south and travelled north with the current. Others came through the Winnipeg River system to Lake Winnipeg and travelled south (upstream) along Red River to Lockport. The ancients witnessed the Great Plains full of bison. They learned to hunt them using their meat for food, their hides for robes and rugs, and their bones for tools and utensils.5 Fragments of Laurel pottery were uncovered in the earth under St. Peter’s Church, East Selkirk.

Laurel Culture people:

- were hunter/gathers

- fished

- knew of ceramics

- ate and harvested wild rice

- used bow & arrow

- used birch bark canoes

- ate bison, elk, moose, deer, beaver, birds, and fish

- made pottery unearthed at St. Peter’s Church, East Selkirk

- vanished around 1160 (12th century) after a severe drought

The Late Woodland Cultures: Blackduck and Selkirk

Woodland: Archaeologists use the term woodland to describe prehistoric sites that existed between hunter-gather societies and agricultural societies. One major characteristic of a Woodland Culture is the progressive difference in the form and decoration of pottery and the common use of corn agriculture.

Archaeologists suggest that two Woodland Cultures resided in the region of Lockport (St. Clements). They called them, The Blackduck Culture and The Selkirk Culture. Pottery style distinguishes each culture.

Blackduck Culture

One of the first discoveries of the Culture occurred near Blackduck Lake in northern Minnesota (USA). Archaeologists referred to the artifacts found as Blackduck. Using radiocarbon dating on the artifacts, archaeologists dated the existence of the people from between 900 BC to 1000 CE (Common Era).

Archaeologists suggest the people of the Selkirk Culture are the ancestors of the modern-day Cree peoples.

Blackduck Culture pottery is a cord-impressed pottery with round-bases and constricted necks with flat, thick lips. Impression was put on the neck, rim, lip, and occasionally on the inner rim, when the clay was wet.6 Archaeological excavations in southern Manitoba and Lockport have uncovered fragments of Blackduck pottery dating to about 900 A.D. (10th century)

Other artifacts associated with Blackduck Culture include:

- small triangular and side-notched projectile points

- a variety of stone and bonehide-scraping tools

- ovate knives

- stone drills

- smoking pipes

- bone awls

- needles

- harpoons and spatulas

- bear and beaver tooth ornaments and tools

- small copper tools and ornaments7

Selkirk Culture

Receiving its name from artifacts found near the city of Selkirk, the Selkirk Culture made pottery of similar style to Blackduck pottery with pots of globular shape with slightly constricted necks and out-flaring rims. This pottery is fabric-impressed, a term used to describe the surface finish of a pot related to the method used to create it.8

Archaeologists say that Selkirk Culture and Blackduck Culture were similar to each other and show a certain level of continuity to the earlier Laurel Culture. Blackduck and Laurel Culture are especially similar in that both cultures made their campsites on the edge of the grassland/forest setting, and both were bison hunters.People of Selkirk Culture lived north of St. Clements in more heavily forested areas near lakes and rivers. Archaeologists suggest the people of the Selkirk Culture are the ancestors of the modern-day Cree peoples.9 Artifacts belonging to this culture were uncovered in the earth under and near St. Peter’s Church, Dynevor (East Selkirk).

Similarities between Blackduck and Selkirk Cultures:

- Both cultures existed between 900 (10th century) and 1700 (18th century).

- Both cultures ate wild rice and left behind fragments of material goods.

- Both cultures buried their dead in mounds.

- Both cultures traded with people from distant lands.

The cultural evolution of the prehistoric peoples of the St. Clements region began with nomadic peoples coming and going from the region seasonally to living in a fixed place for longer periods. Initially the early peoples ate bison primarily, followed by a culture that incorporated other large and small animals to their diet, as well as fish, berries, and plants. Their tools and technology evolved from stone tools and atlatls (spears) to bow and arrow, and copper tools.

What can be learned from studying prehistoric culture?

To study prehistoric culture is to reconstruct the life ways and movements of humanity throughout time. By studying earlier cultures, our modern minds begin to see the connections between and among cultures and create a map that shows cultural change over time. The things left behind, hidden by time and soil, leave a story about the animals that roamed the lands, the people who followed them, and the ways of survival and evolution for both.

Archaeologists say the First Peoples of Canada were the first immigrants, arriving from Asia by crossing a land bridge that once joined Alaska and Siberia. First Nation descendants say they have always lived on this continent. They call it Turtle Island.

1100 Years Ago to 300 Years Ago

Ke-no-se-wun:The Lockport region was important for its abundance of fish. The region lies below a long set of rapids where fish came to spawn. The ancients could net and/or spear many fish, and so they named the region Ke-no-se-wun, a Cree word to mean, “There are many fish.”

Agricultural Time

Agriculture has deep roots in St. Clements. Archaeological digs done at Lockport show people were farming in the region as early as 900 (10th century). This means the region’s agricultural roots are over 1000 years old.

Those early people domesticated wild plants and planted corn that they brought with them from other regions. They may have planted other vegetables too that modern archaeology has not yet discovered. The soil was full of nutrients from the sediments of Lake Agassiz and the flooding of the Red River each year. Various agricultural artifacts have been uncovered on the east bank of the Red River. They include:

Whoever the early farmers were, they stopped farming at Lockport sometime during the 15th century because the climate in Lockport, and all of Manitoba, changed. The province turned cold with shorter, cooler summers and longer, colder winters.

- stone tools

- bone tools

- ceramic vessels

- underground storage pits

- charred corn kernels.

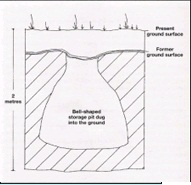

They planted corn in rows of small hillocks several feet apart with several kernels placed in each mound. The people ate fresh corn and stored it for later use using bell-shaped shortage pits in the ground that were lined with dried grasses, bark, or tanned hides preventing the stored food from spoiling. The largest pit found at Lockport measures 1.26 metres wide at its base (over 4 feet) and 1.37 metres (4.5 feet) deep.10

Who were these early farmers?

No one knows for sure who those early farmers were. Archaeologists think a clue to their identity might lie in the pottery. Some pottery fragments uncovered in Lockport are similar in style and pattern to the vessels found in early camps along the Missouri River.11 Those camps belonged to the peoples of the Arikara, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Gros Ventre Nations. Those southern camps were not more than a few days travel from the Lockport area making it easy for people to travel between the two places.

Peoples of the Mandan and Hidatsa cultures were corn farmers. In the early 1900s, an elderly Hidatsa woman named Maxidiwiac “Buffalo Bird Woman” told researchers about early farming practices of her people. She said Hidatsa women were responsible for soil preparation, planting, weeding and harvesting.12 Women made hoes from the shoulder blades of bison and rakes by tying a set of deer antlers to a stick. The ancestors of the Mandan and Hidatsa cultures may have been Lockport’s early farmers. They may have come to the region because of its rich farmland and abundance of large game and fish. These were important food sources in addition to corn, wild rice, vegetable, and plant.Whoever the early farmers were, they stopped farming at Lockport sometime during the 15th century because the climate in Lockport, and all of Manitoba, changed. The province turned cold with shorter, cooler summers and longer, colder winters. Farming and fishing became impossible. The people moved to warmer climates, perhaps returning to the Upper Missouri River.

Nearly 500 years later, the evidence reveals the first farmers in the region of Lockport and St. Clements were the ancestors of today’s First Nations peoples, not Europeans as so many European writers suggest.- Agricultural time was between 900 -1750

- People of this time were agriculturalists, fishers, hunters, and gathers

- A period of domesticated corn kernels

- Bison bone scapula hoes were a main tool

- Deer antlers were made into rakes

- Women and children were the gardeners and/or farmers

- Grinding stones were used for milling plant seeds

- Underground pits to store the fall harvest were dug

- Pottery style found in Lockport suggest links to farming communities on the Upper Missouri River in the USA

Historical time – After 1600

Several groups of First Nations people lived in the St. Clements region within the time of historical record. Three of them include:

- Assiniboin/e (Nakota)

- Cree (Plains and Northern)

- Saulteaux (Ojibway)

Assiniboine (Nakota)

Some sources say the tribal name Assiniboin/e came from the Cree peoples. Cree elders say their ancestors called the Assiniboin/e peoples, “Assee-nee-pay-tockor Assinipoet meaning Stone Water People.They called them this name because they saw them putting hot stones into rawhide-lined holes in the ground to cook their food.”13 Assiniboin/e peoples were also called Stoney Indians for the same reason. Many Assiniboine/e people referred to themselves as Nakota.

Descendants of the Sioux

Assinboine Warriors painted by Karl Bodher, ca. 1830. Source: Library and Archives Canada [click to enlarge]

Some groups made their camps along the Assiniboine River. When European fur traders came to the region, and saw their camps and heard their name, they called the waterway, Assiniboine River. This river meets the Red River at the Forks in Winnipeg.

Archaeology done in the Lockport area has uncovered ceramic called Sandy Lake or Psinoman. This ceramic belonged to the ancestors of modern day Assiniboine peoples.15 Jesuit priests residing in missions in southern Ontario referred to Assiniboine peoples living in the Manitoba region in the mid 1600s. Perhaps the ceramic evidence shows their ancestors lived here long before that.

Most Assiniboine groups formed trade networks with the Plains Cree peoples and with French and English/Scottish fur traders after they arrived in the region. They became guides, traders, and interpreters. Some Assiniboine men provided food to European trading posts on the Plains, and Assiniboine women made footwear, coats, and snowshoes for those fur traders. Some Assiniboine women married Cree, French, and English/Scottish men.

During the historical period, the population of Assiniboine peoples declined rapidly due to European-introduced diseases.

Although historically, Assiniboine peoples were once residents of the St. Clements region, today there are few, if any descendants, living in the region. Most families moved westward from the Great Plains of Manitoba and Saskatchewan to Alberta and Montana.

Cree: Plains and Northern

Archaeology suggests the people of the prehistoric Selkirk Culture are the ancestors of the modern day Cree peoples. Therefore, the Cree people have been a part of the Manitoba landscape for a long, long time.

Non-Cree people gave the name, Cree, to this nation of people. It is a generic term that is common today, but most Cree peoples call themselves names that are more specific to their environment. Some examples in the English language include:

- Plains Cree

- Swampy Cree

- James Bay Cree

- Moose Cree

- Rock Cree

- Woodland Cree

All groups of Cree peoples use their own language to identity themselves. For example, the Swampy Cree people of James Bay call themselves Omushkego (People of the muskeg).

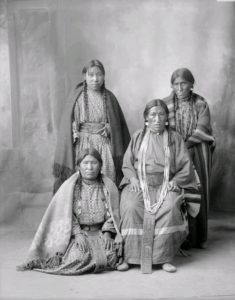

Historically, Cree peoples have resided in Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and North West Territories. Bands have resided throughout the province of Manitoba from Hudson Bay to the southwestern Plains. The northern Cree ate mainly caribou, moose, and bear. The Plains Cree primarily ate bison (buffalo). The Plains Cree formed alliances with the Blackfoot and Mandan peoples in the south from which they traded horses. They were then able to chase buffalo/bison. They hunted with lances, and bows and arrows, before the introduction of the musket (gun) from European fur traders.Cree Women:

- butchered the game

- scraped the hair from the hides

- tanned the hides, using the brain of the animal. They mixed water with the brain to make a paste that they spread on the hide to soften it as it dried.

- hung the hide in smoke to tan it. This process made the hide waterproof.

- women made moccasins, mukluks, mitts, and coats from the hides.

- after the arrival of European cloth, women sewed dresses and skirts from colourful fabric, much of it plaid in design.

Cree peoples lived in tipis/tents that were in the shape of a cone, larger at the bottom with a hole at the top to allow the smoke to rise up and blow away. Tamarack trees provided the poles for the tipi. Tamarack trees are tall, straight, and strong. Each group used a certain number of poles that had meaning for them. Some Cree peoples used 15 poles, others 13, and yet others 18. Each pole contained a teaching, such as obedience, respect, humility, etc. Buffalo hides covered the poles. It took eighteen bison hides, sewn together, to make a tipi twelve feet in diameter.16

Plains Cree people were early residents of the St. Clements region. They traded with other First Nations people to the south and with French and English/Scottish fur traders when they came to the region.

Northern Cree peoples lived along Hudson Bay and throughout the northern landscape of what it now called Manitoba. Many Cree men became friends with European fur traders who worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company. They became middlemen for the Hudson’s Bay Company, transporting goods from the north to the inland people, making trade for furs, and returning to Hudson Bay with the furs.

Many Cree women married English and Scottish men who worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company – their children were termed half-breed by others not of the lineage.

Saulteaux (Ojibway)

Saulteaux (Ojibway) people migrated to the region of St. Clements in the mid to late 1700s. Their ancestral tribal name is difficult to determine because they have been called so many names over the last 300 years. During the early 1700s and before that time, this cultural group of people resided near the rapids on the St. Mary’s River (Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario). There, they encountered French fur traders from Quebec. Observing the people spearing fish in the river and jumping across the rapids to do this, the early traders referred to the people as Saulteaux, a French term that means people who jump or shoot the rapids.17

Other tribal names for the Saulteaux include Ah-nish-in-ah-bay, Outchibouec, Chippewa, and Ojibwa/y. Several Saulteaux men made trade connections with French fur traders and several women formed marital unions with those same traders based on Saulteaux marriage ceremony. Their children are Métis meaning to-mix.

Today, descendants self-identify as:

- Saulteaux

- Ojibway

- Anishinaabee

During the 18th century, some groups of Saulteaux peoples moved westward into the region of present day Manitoba, and many made their home in the St. Clements area.

Saulteaux man, possibly Chief Peguis, Sketch by Peter Rindisbacher, Archives of Manitoba [click to enlarge]

Chief Peguis

Peguis is one of the better-known Saulteaux (Ojibway) leaders who resettled in the St. Clements region. He was born in 1774 in Sault Ste. Marie (Ontario) to a young Saulteaux mother and a French father. As a young man he migrated west with his Band to Red Lake Minnesota. They moved northward to Pembina (North Dakota) where they traded furs with traders from both the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company.

Sometime during the 1780s, Peguis and his people migrated to the forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. They paddled north to Netley Creek where they found a large band of Cree peoples, and some Assiniboine peoples, dead in their camp.

There are two stories that explain the reasons for the deaths. The first story says that smallpox, a highly infectious disease with fever and flue-like symptoms and blister-like sores on the skin, caused the deaths. It spread rapidly among the people.

The second story says that the region was where the Cree and Assiniboine peoples made camp. During the summer, the men went to York Factory, Hudson Bay to trade their furs. The old people, children, and women remained in camp. A large band of Dakota Sioux attacked the camp and killed those who remained.

Whatever the truth is, when Peguis, and his people, arrived they witnessed the decimation of a whole band of people. They called the waterway, Nee-bo-win Seepee, (various spelling exist in archival records) meaning Death River or River of Death in English.18

By at least 1808, English fur traders were calling the waterway, Netley Creek.19

By Donna Sutherland

- Wikipedia “Lake Agassiz” at http://wikipedia.org

- The Prehistory of the Lockport Site,” Manitoba Culture, Heritage, and Recreation (Historic Resources Branch), 1985. p. 2; also “Land Below the Forks: Archaeology, Prehistory and History of the Selkirk and District Planning Area,” by K. David McLeod (Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Recreation), 1987, p.33

- A Glossary of Manitoba Prehistoric Archaeology at: www.umanitoba.ca; also K. David McLeod, “Land Below the Forks…” p. 33

- K. David McLeod, “Land Below the Forks”, p. 37

- The Prehistory of the Lockport Site,” Manitoba Culture, Heritage, and Recreation (Historic Resources Branch), 1985. pages 5-10.

- A Glossary of Manitoba Prehistoric Archaeology at: www.umanitoba.ca

- A Glossary of Manitoba Prehistoric Archaeology at: www.umanitoba.ca

- A Glossary of Manitoba Prehistoric Archaeology at: www.umanitoba.ca

- Ibid; Also The Prehistory of the Lockport Site, p. 15

- First Farmers in the Red River Valley (Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Citizenship, Historic Resources) p. 5

- Catherine Flynn & E. Leigh Syms “Manitoba First Farmers” Manitoba History, Number 31, Spring, 1996 at: www.mhs.mb.ca

- Catherine Flynn & E. Leigh Syms “Manitoba First Farmers” Manitoba History, Number 31, Spring, 1996 at: www.mhs.mb.ca

- Assiniboin (Nakota) First Nation, Manitoba Culture, Heritage, and Citizenship/Historic Resources, p. 1

- Edwin Thompson Denig (edited by J. B. Hewitt) “The Assiniboine” p. 1

- Assiniboin (Nakota) First Nation, Manitoba Culture, Heritage, and Citizenship/Historic Resources, p. 2

- Ruth Christie, “Canadian Tales from the past,” edited by Donald S. MacDonald, p. 37

- Donna G. Sutherland, Peguis: A Noble Friend, p. 1

- Donna G. Sutherland, Peguis: A Noble Friend, 22

- Donna G. Sutherland, Peguis; A Noble Friend, p. 30