In the Beginning

Canada was a new country at the end of the 19th century with a low population of immigrant people. The majority of people living in Canada then, especially in western Canada, were First Nations and Métis peoples. The Prime Minster of Canada, Wilfrid Laurier, wanted to increase the country’s immigrant population in the west and offered the people of central Europe “free land” if they agreed to immigrate to Canada. Many people accepted the offer, and so began a new journey and a new way of life for many European peoples.

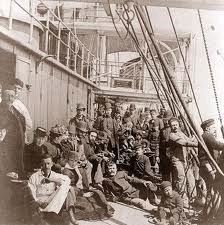

Families sold their land and their homes to pay for the ocean passage to Canada. They brought few things with them when they left their homeland. Items such as clothes, small handmade tools, seeds of grain to plant in Canadian soil, blankets, dishes, and other small personal things were all they had. The ocean passage took about a month and conditions on the ships were very bad. Ships were overcrowded and the living quarters housed far more people than was comfortable or sanitary. There were no proper toilets. The ship’s crew fed the people soup, bread, biscuits, oatmeal, and fresh water. The overcrowding, poor hygiene, and improper diet caused illness and even death to some people.

The ships docked in the ports of Halifax, 4Nova Scotia and Montreal, Quebec. After the people disembarked from the ship, they boarded trains to take them west to Manitoba and beyond. The trains were also overcrowded with people. The people sat or laid on wooden benches and beds that were uncomfortable. Many people arrived at the Immigration Shed in Winnipeg and then re-routed to East Selkirk.

The First Arrivals

In February 1899, the first group of Russian Doukhobors, about 1700 in total, arrived in East Selkirk to take up residence in the old Round House, a building that the Canadian Government converted into an Immigration Shed. Living conditions in the Immigration Shed were not good. The building was cold, poorly heated, poorly ventilated, crowded with people, and designed for a completely different purpose. Several people became ill from disease and living in a cold, overcrowded building. On 1 March 1899, a four-year-old girl died of pneumonia.

The people were exhausted when they arrived. They had endured a long and difficult ship’s passage across the Atlantic Ocean and a slow and grueling train trip from eastern Canada to Manitoba. They coped with sadness and the stresses of eviction from their homes and homeland, and the separation from family and friends who had not immigrated. Many others coped with the death of loved ones along the way as they made their trip to Manitoba. The newcomers did not understand the language or the geography of Canada nor the customs and the people of this new country.

After the first group of Doukhobors settled in the East Selkirk Round House, a large group of people from Ukraine, especially from the provinces of Galicia and Bukovyna arrived. Other groups of people from the same countries as well as people from Poland, Austria, and Latvia followed over the next months and years.

The Immigration Shed in St. Clements

Built from stone at a nearby quarry and brick from a manufacturing plant in East Selkirk, the Round House was an enormous building. It was about 90 feet wide and 180 feet deep with a stone foundation and 4 wings or extensions. The ceiling was high, especially in the area of the turntable. It also held a cellar beneath the building. The Canadian Government built it south of Colvile Road on Frank Street for the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) to maintain and repair its train engines.

The building of the Canadian Pacific Railway was a critical first step in making immigrant settlement in the Canadian prairies possible. The railway would become the new way to transport people and cargo inland. When the Canadian government decided to build the railway, they hired Sanford Fleming to survey the best possible route for the future transcontinental railway. He arrived in Selkirk in 1872. He said Selkirk was a good spot to build a bridge for the railroad to cross Red River. Its high riverbanks would protect the bridge from destructive floodwaters.

However, the Canadian Pacific Railway never built their railway bridge at Selkirk. The railway diverted south to Winnipeg and crossed the Red River there. The Government abandoned the Round House. It sat vacant for many years, until the Canadian Government decided to convert the building into an Immigration Shed to house incoming immigrants. The building required a lot of work, after all, it had been built to repair train engines, not to house people. Workers installed ten caldrons of 60 gallons each to hold water, twelve box-stoves, two large and four small stoves for cooking, and a few bathtubs to bathe in. Two wells were dug nearby for drinking water, and toilets were outside. Government officials said the building was capable of housing 1500 to 2000 people at one time.

And that may have been true, but it certainly did not house them comfortably. The additions and changes that were made were simple and unrefined. When the first Doukhobors arrived in February of 1899, the building was cold, damp, and packed with people.

In April of 1899, the 1700 Doukhobors had to make room for 600 new immigrants arriving by train. This group of people came from Ukraine in the province of Galicia. Their culture, custom, language, and traditions were completely different to those of the Doukhobors, but the Canadian Government believed they would get along. Few records remain to say if they did. One month later, another group of about 1000 Doukhobors made their way to East Selkirk, followed by an even larger group. The Round House was not large enough to house all those people, so the government erected large tents to provide more space. The people did not remain in the Round House. Over the summer of 1899, they boarded trains that took them west to settle on land in the provinces of Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia.

However, many Ukrainian, and some Doukhobor, Polish, and Latvian immigrants remained in East Selkirk, settled on lands in East Selkirk, Libau, Ukrainian Oven The Beaches, Gonor, Narol, Thalberg, and Walkeyberg, and established communities. Many of their descendents live in these communities today.Immigrants from Ukraine

The largest group of European peoples to immigrate to Canada, and more specifically to the prairies, came from Ukraine. The majority of people came from the western portion of Ukraine in the provinces of Galicia and Bukovyna. About 170,000 Ukrainians traveled to Canada between 1891 and 1920. Most Ukrainian people practiced the Catholic religion and brought many of their traditions with them to Canada including legends, songs, music, art, dance, food, and clothing. They spoke Ukrainian, the official language of Ukraine. It is a Slavic language with 33 letters in the alphabet, called Cyrillic alphabet. Some letters look like Greek symbols. Each region in Ukraine speaks a different dialect.

Doukhobors from Russia

People of Doukhobor heritage were/are a Christian group of Russian origin whose religious practice dates to the 17th century Russian Empire. The term Doukhobor means Spirit Wrestlers. The Russian government forced many Doukhobors to fight for the Czar, the then Slavic monarch, Nicholas II of Russia, whose rule between 1894 and 1917 brought death and destruction to many people. When they refused, the government sent them away to isolated parts of Siberia or jailed them. Canada offered the people free land, a right to their own religion, and guaranteed no military service. Thousands of Doukhobors agreed to relocate to Canada. Many were so poor that they could not afford passage to Canada. Other religious organizations such as the Quakers and Tolstoyans sympathized with their plight and paid their passage, as did the famous author Leo Tolstoy by offering them the royalties from his novel, Resurrection.

Doukhobors were mostly vegetarians eating a diet of bread, rice, barely, butter, sugar, tea, cheese, potatoes, cabbage, and molasses, rolled oats, onions, salt/pepper, and citric acid to “sour their soup.” The first group of Doukhobors arrived in East Selkirk in February 1899 and about 6,000 others migrated to Canada over the year settling on granted land in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Other groups followed with many settling in Alberta, and British Columbia.

Immigrants from Poland

Another large group of people to immigrate to Canada and settle on the prairies, and in East Selkirk, came from Poland. There was a shortage of jobs and land in their native Poland. This forced thousands of people to seek employment elsewhere. The Canadian Pacific Railway publicly campaigned in Poland promoting employment opportunities in western Canada for those considering immigration. Approximately 120,000 people came to Canada between 1895 and 1913. Some people became farmers and worked the land while other worked on the railway and in mining. Most polish people practiced the Catholic religion.

The Homestead Act

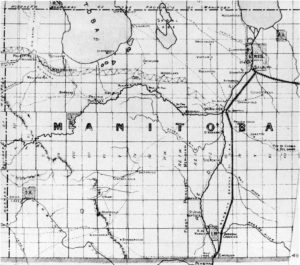

The Canadian Government offered land to each immigrant family for a small fee through The Homestead Act. Immigrants were required to pay about $10.00, build a house, clear a percentage of the bush off the property, and establish a farm within three years. Once they did that, the land was theirs. Immigrants choose their homestead from a map in the local immigration office which surveyors had divided into homesteads prior to the immigrant’s arrival. Surveyors laid out townships into six-mile squares (section) with each square (section) measuring 640 acres. They divided them again into four-quarters. The land act said that anyone over 21 could make a claim for a quarter section of land.

Doukhobors preferred to live in communal communities rather than individually, and so the Homestead Act amended their original plan to include the Hamlet Clause, which allowed people to settle together. This was especially so in the western provinces.

Where did the people go?

After a temporary stay at the Round House, the people either moved west by train to Saskatchewan, Alberta, or British Columbia or staked their Homestead land claim in Manitoba. For those who remained, they settled in the regions of East Selkirk, Libau, Poplar Park, The Beaches, Garson, Lockport, Gonor, Narol, Thalberg, and Walkleyburg. Many descendants of those early settlers continue to live in these communities.

How did they begin?

As soon as the people arrived on their homestead, they began clearing the land of bush. Most families built near one another sharing the hardships of starting their farms. They cared for each other and helped each other in times of need. Many families intermarried so their descendants can tell both sides of the ancestor’s struggles and experience.

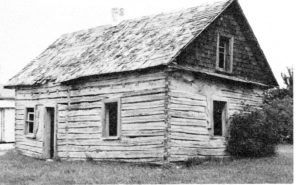

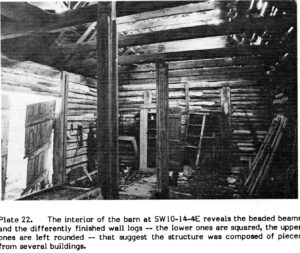

The Ukrainian settlers initially built shelters called “budahs” or “zemliankas.” They were crude one-room huts, lean-tos, or tent-like buildings that sheltered the family while they built the main house. When they were able to build a more substantial house, they did so with logs. They cut down trees, peeled the bark of the tree, and then notched out each end so the logs fitted snugly together. They cut holes in the logs for doors and windows and a chimney. Chimneys were made of stone. They filled the space between the logs with mud plaster from a mixture of water, mud, and grass.

Some families went one-step further and painted or “whitewashed” their houses. They gathered limestone rocks from the fields and burned them over hot fires to extract a powdery chemical called lime. They mixed the lime with water then painted the whitewash over the plaster. This gave the house a clean appearance and helped to reduce drafts. The people brought this custom with them from their homeland. The people covered the roofs of the houses with grass tightly bound and fitted together. Often, the men had to find work elsewhere to earn enough money to support their families. Some men found work at the Garson Quarry, on the construction site of the Lockport Dam, with the Canadian Pacific Railway, and in Timber camps on Lake Winnipeg. It was up to the women and children to keep the farm going. They cut, chopped, and hauled wood to heat the shelter and barn. They collected snow to smelt for drinking and washing, and worked in small, cramped quarters with a small stove to bake their bread and cook their food. The women raised the children, tended the gardens, and cared for the livestock. It was an extremely hard existence for the immigrants during their first few years of residency in Canada.The people of Ukraine built houses in the style of their homeland.

Galician-style Houses

Settlers who came from the region of Galicia, Ukraine built houses similar in design to those of their homeland. However, lack of money and time did not allow them to follow the traditions completely. The style they tried to follow, which scholars today call Galician-style was a log house with a simple thatched gabled roof. A gable roof is the triangular portion of a wall between the edges of a sloping roof. They peeled logs and connected them at the corners with either a dovetail joint for a saddlenotch joint. Each log fitted atop the next. The people often plastered or whitewashed the exterior wall. A wall divided the interior into two rooms. These houses had a life span of about ten years.

Bukovyna-style Houses

Settlers who came from the region of Bukovyna, Ukraine built houses similar in design to those of their homeland. Today, scholars call them Bukovyna-style. The Bukovyna folk house was a little larger than the Galician house with three rooms and a doorway in the middle that opened to a small entryway called a “siny.” Houses were also made of log and generally had a hipped-roof as well with overhanging eaves. A hipped-roof means that all sides slope downwards to the walls giving the building the shape that somewhat resembles a pyramid.

What did they do?

Many families settled in a region near to each other. Once they were established, many families in the more rural areas became grain and cattle farmers. They purchased oxen and horses, and cleared and cultivated the land in preparation to plant vegetables, potatoes, and grains. Some families started a general store for the other people to purchase supplies and dry goods. As the community grew, it received a post office that normally took on a name from the immigrants’ homeland, such as Libau, Narol, and Gonor. The people built schools for the children and churches for the community to worship in based on the architecture of their homeland.

Several families living between East Selkirk and Narol became vegetables gardeners. In the fall they harvested their crops, loaded the produce onto wagons (often pulled by oxen), and hauled their wares to the north end of Winnipeg where they set up booths to sell their vegetables. Before the construction of the Lockport Bridge, the path to Winnipeg followed the east side of Red River to the Redwood Bridge, Winnipeg. Many second and third generation descendants continued the tradition started by their ancestors. They received the name Market Gardeners.Glossary

Budahs: an early shelter for Ukrainian immigrants

Bukovyna (Bukovina): a province in Ukraine

Cyrillic alphabet: Ukrainian alphabet

Doukhobor – a person of Russian heritage of a particular religious practice

Dovetail join: a joint in cabinetry and square log construction consisting of interlocking “V”-shaped cuts

Emigrate: leave a country

Emigrant: a person who has left a country

Galicia: a province in Ukraine

Immigrate: go to a new country

Immigrant: people who have come to one country from another country

Immigration Shed: a place where immigrants stayed when they first arrived in a new country

Round House: Engine House built to repair and maintain trains

Saddlenotch joint: a join at the corner of a log cabin construction to fit two logs together

Zemliankas: the name of an early shelter for Ukrainian immigrants

Sources:

Butterfield, David. Architectural Heritage: The Selkirk and District Planning Area. (Winnipeg: Manitoba Culture, Heritage, and Recreation, 1998)

Hodge, Deborah, The Kids Book of Canadian Immigration (illustrated by John Mantha) (Toronto: Kids Can Press, 2006)

Hudak, Healther Ukrainians in Canada (Calgary: Weigl Educational Publishers, 2005)

Hughes, Susan Coming to Canada: Building A Life in a New Land (Toronto: Maple Tree Press, 2005)

Laberge, Jared Preserving Our History One Story At A Time (Manitoba: St. Clements Heritage Advisory Committee, 2004)

Potyondi, Barry Selkirk: The First Hundred Years (Barry Potyondi, 1981)

Rural Municipality of St. Clements East Sideof the Red 1884-1984 (St. Clements: R.M. of St. Clements, 1984)

Web sites

Wikipedia “Doukhobors” at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doukhobor