Architectural Heritage of St. Clements

“Starting afresh in a new home has always been a part of prairie life” (Holt 1). St. Clements municipality has attracted many different social and ethnic groups throughout history. These groups each brought their own distinctive influences which combined to form the great multicultural history of our region. The major development in St. Clements began with the arrival of the First Nations peoples and continued with the arrival of Scottish settlers and Ukrainian immigrants; each of these groups brought new and different methods of constructing permanent wood and stone structures. The unique styling of their architecture is a testament to the times and lifestyles of each group.

Native Structures (Pre-European History)

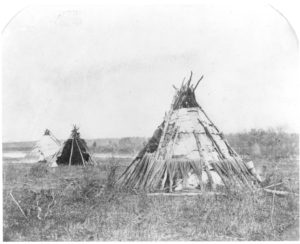

The first man-made structures present in Manitoba were those of the First Nations peoples. The First Nations peoples were present in Manitoba as early as 6500 B.C. The Larter, Laurel, and Selkirk Cultures all left their mark living along the Red River, in current St. Clements. The most common abode of these groups was the teepee. These were cone shaped structures made of poles, lashings, and animal skins.

To erect the tipi, three long poles were laid on the ground and lashed together at one end with a long strip of rawhide. The poles were raised and the legs of the resulting tripod were spread apart. An extra length of the rawhide lash extended to the ground, where it was staked to stabilize the structure. According to the size of the tipi frame, the total number of secondary poles varied. The Cree added thirteen poles, arranged in a counter-clockwise direction, to the basic three-pole framework (Butterfield 16).

The most common skins used were Bison. The skins were stretched around the structure with one elliptical opening for an entrance. The only other opening on the structure was known as the ear; this was the smoke hole, located at the topmost point. Interestingly enough “the secrets and skills of building teepees from tanned buffalo hides and poles were passed among women from generation to generation” (Holt 3).

The most common skins used were Bison. The skins were stretched around the structure with one elliptical opening for an entrance. The only other opening on the structure was known as the ear; this was the smoke hole, located at the topmost point. Interestingly enough “the secrets and skills of building teepees from tanned buffalo hides and poles were passed among women from generation to generation” (Holt 3).

Selkirk Culture

The teepee is a testament to the resourcefulness of the Native American culture. These structures could be adapted for all seasons. In the winter, “an attached wall of buffalo hides was often used to line the inner sides of the tipi. Hay was stuffed between this screen and the tipi cover” (Butterfield 17). In summer, to increase ventilation, “the bottom of the cover could be rolled up on the poles to a height of about one metre from the ground” (Butterfield 17). These structures were easily assembled or disassembled, which suited the purpose for these nomadic peoples.

The spirituality of the construction of a teepee was also very important to the First Nations culture; a ceremony was held with each creation of a tipi. With the killing of the bison also came a ritual meal. The entire clan assisted in the sewing and creation of the new structure, sometimes even adding decorative paintings. In a tipi, “the place of honour was behind the fire, opposite the door” (Butterfield 16).

Several other structures present in the Native American Culture include the sweatlodge, a dome-shaped structure built from arched willow branches and buffalo hide covers, and the sapohtowa’n and the wewahtahoka’n, which were used for special dances.

First European Settlers (1750-1869)

Red River Frame Houses

With the arrival of Europeans came a great change in architecture. Since the teepee was not considered a permanent enough structure, the Hudson’s Bay Company men developed their own European style log housing, and later, with the arrival of the Selkirk Settlers, stone structures were being created.

From 1750-1869, the most common structure along the Red River was the Red River Frame House. The origins for this design come from the maison en columbage in New France. Although this style did not fare well in extreme winters, the Hudson’s Bay Company men adapted this design for the Red River settlement. When the Selkirk settlers arrived, they took to the structures immediately, developing their forts, churches, and housing in this style. The foundations for these buildings were commonly fieldstone or limestone.

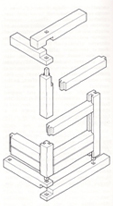

Red River frame buildings consisted of comparatively long vertical posts and shorter horizontal logs that were combined to form the four walls. To produce the frame, the vertical logs, squared at least on two sides, were connected by mortise and tenon joints to the bottom sill logs – which for greater moisture resistance and load-bearing capacity, were often of a harder wood than was used in the rest of the building (Butterfield 19-20).

The frames on the structure were constructed with projections on each side, so that the pieces would fit together in a puzzle like manner. Because of this, few nails were used in the construction and additions were easily created. The roofs on the buildings were originally thatched, and sealer/plaster was created from local mud. Much of the wood for the structures was obtained at heavily pine forested areas, currently near the beaches of St. Clements. The housing interior was then separated into as many as three rooms with makeshift walls.

River Frame houses were developed in such a way so that “the short logs could expand and contract with variations in temperature without being dislodged [… which made] a durable structure resistant to the climatic extremes characteristic of Manitoba” (Butterfield 20). A first hand account of the housing describes the buildings as follows:

It is a log cabin, like all of this class (some far better ones have walls of stone) with a thatched roof and a rough stone and mortar chimney planted against one wall. Inside is but a single room, well whitewashed, as is indeed the outside and exceptionally tidy; a bed occupies one corner, a sort of couch another, a rung ladder leads up to loose boards overhead which form an attic, a trap door in the middle of the room opens to a small hole in the ground where milk an butter are kept cool; from the beam is suspended a hammock, used as a cradle for the baby; shelves singularly hung hold a scanty stock of plates, knives and forks; two windows on either side, covered with mosquito netting, admit light, and a modicum of air; chests and boxes supply the place of seats with here and there a keg by the way of an easy-chair (Butterfield 21).

William Cockran, one of the first ministers of St. Peter’s Church, described a house in the St. Peter’s Settlement as follows: “The seams of the log walls were plastered with mud; the chimneys were of the same material; the roofs were thatched with reeds and covered with earth; the boards of the floors, and doors, and beds, were planed with the saw and the windows were formed of parchment made of the skins of fishes” (Butterfield 21)

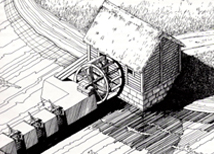

Within the farming community numerous schools, barns, storage houses, and granaries were built in the Red River Frame style. On the east side of the river, special note is given to Gunn’s Mill which was located on the banks of Gunn’s creek in present-day Lockport. Constructed in the Red River Frame style, the mill measured 8 x 11 metres and was two stories high. However, one major difference from the Red River style was the lack of chinking in the walls; this was due to the continuous vibrations of the mill wheels, which shook all chinking loose.

Stone Buildings

Stone houses became more common after the consolidation of the Red River settlement. The more prestigious members of the community sought to construct sophisticated stone structures. Although most examples occur at Lower Fort Garry, one example in St. Clements includes the Thomas Bunn House. The majority of these stone influences came from the Orkney Islands, courtesy of the Hudson’s Bay Company men.

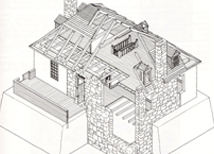

The Thomas Bunn house is the “most well preserved example of a single storey stone house in the province” (Butterfield 36). This building was built for Thomas Bunn, who was a lawyer, politician, and a member of Louis Riel’s first provisional government. The mason in charge of construction was Samuel Taylor, who built the structure between 1861 and 1864. The stone for the house was quarried from the banks of the Red River and collected from local fields. Lime was burned in a kiln to create powder, used as mortar. The building measures 28 feet by 40 feet, and the stone walls are one metre thick.

The rafters were squared timbers fastened at the peak with wooden dowels. The lower end of each of these rafters was seated in a wooden beam that, joined with another, was anchored atop the stone wall. The attic, which contained the four bedrooms, was lighted with five dormer windows. The main floor was separated into three rooms: a parlour, a kitchen and a dining room (Butterfield 36).

An examination of the architecture in St. Clements municipality would not be complete without St. Peter’s Church. Originally a wooden church, the stone church was built under the leadership of William Cockran in 1853, and is the second oldest stone church on the prairies. It is located in what was the first Aboriginal agricultural settlement in Western Canada. The stone for the church was quarried from the banks of the Red River. The foundation for the church measured one metre deep and one metre thick.

“Stones for the walls were lifted into place by block and tackle and set with mortar produced at a nearby kiln. Glass for the windows was shipped from Britain” (Butterfield 45). The rafters for the church, measuring eight metres long, were floated down the river. A stone wall was also constructed around the church and cemetery, but it has since been torn down. The original bell tower was dismantled and the current wooden tower has been present since 1904. Today the church still contains the original hand-hewn pews, carved pulpit, and altar rails.

As settlement increased, more and more types of Scottish/English style homes were created, with some influences coming from Ontario.

Eastern European Influences (1890 – 1920)

In the 1890’s Ukrainian immigrants began arriving from East and Central Europe. In the town of East Selkirk there was an Immigration Shed, which was originally a CPR roundhouse refitted to house immigrants. Because of its existence, many Ukrainian/Galician groups settled in the Rural Municipality of St. Clements. With them came their traditional designs for homes and farm buildings which had “reached a high level of skill and artistry” (Butterfield 77).

In the 1890’s Ukrainian immigrants began arriving from East and Central Europe. In the town of East Selkirk there was an Immigration Shed, which was originally a CPR roundhouse refitted to house immigrants. Because of its existence, many Ukrainian/Galician groups settled in the Rural Municipality of St. Clements. With them came their traditional designs for homes and farm buildings which had “reached a high level of skill and artistry” (Butterfield 77).

“The traditional Ukrainian farmyard included several buildings besides the house and the barn, or stodola. Pigs were housed in a Khliv and poultry in a kurnyk. Grain was stored in a spitlair, while summer food preparation took place in the kuchny. A distinctive little building, the komora was used for dry storage and as a tool shed. Other standard items in a Ukrainian farmstead typically included an outdoor clay and stone bake oven, a crib well with a tall sweep of balance beam for drawing water, a small outhouse and, in some cases, and open structure used as a sheltered work area” (Butterfield 77).

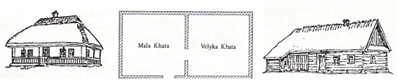

The basic structure of a Ukrainian home included the rectangular house, separated into two rooms. The first was the mala khata, a small room located at the west end of the building, where the daily activities occurred including cooking, eating, washing and sleeping. This room also had the cook-stove or pich which was used as a bed for children in the winter months since it gave off heat, even after the fire had burnt out. The second room was the velyka khata or the large room, located as the east end of the house. This room was used primarily for festive occasions, such as Christmas and Easter. Religious icons, pictures, and embroidery/stitching were hung on the east wall.

Three different methods of log construction were used. These included horizontal, post and fill, and vertical log construction. The most similar to the Red River frame style was the post and fill method. “The Ukrainian cottage was usually finished inside and out with a thick layer of plaster. The plaster consisted of a mixture of clay, sand and water, supplemented with a combination of chopped straw and horse or cow dung to prevent it from cracking as it dried” (Butterfield 78). One feature that distinguished Ukrainian structures from neighboring buildings was the steep thatched roof.

In the municipality of St. Clements two distinct regional variations were present; they were the Galician and the Bukovynian style housing. The Bukovynian homes were commonly more elaborate and larger than the Galician style. “Bukovynian houses were usually three-roomed structures with a centrally located doorway which opened onto a small entrance hall called a siny” (Butterfield 79). Decorative trims and patterns were commonly applied to the outside wall and a verandah was usually present. Galician homes were commonly two room structures with a simple gable or hipped gable roof, and they did not have the prominent overhang of the Bukovynian houses.

“Both Bukovynian and Galician farmyard structures – barns, granaries, chicken coops, work sheds and storage sheds – were constructed, like their dwellings, on a rectangular plan with mud-plastered log walls and thatched roofs” (Butterfield 79). In addition to the farming settlements, churches in the region were also elaborately constructed, reflecting original European design.

Throughouht the history of St. Clements, many historical buildings have dotted its landscape. Each structure brought a truly unique culture to this region, helping develop the multicultural history that is prized by the entire nation. Although many of the structures are no longer standing today, their historical ties remain as the foundation of present day architecture.

Article written by Jared Laberge St. Clements Heritage Advisory Committee – 08/09/2007

Sources

Butterfield, David. Architectural Heritage – The Selkirk and District Planning Area. Manitoba Heritage, Culture and Recreation – Historic Resources. 1988.

Historic Resources Branch. The Prehistory of the Lockport Site. Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Recreation, 1985.

Holt, Faye Reineberg. Settling In – First Homes on the Prairies. Calgary, Alberta: Fifth House LTD., 1999.

Piniuta, Harry. Land of Pain Land of Promise – First Persons Accounts by Ukrainian Pioneers 1891 – 1914. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1978.

Slh, St. Clements Historical Committee. “Thomas Bunn A St. Clements Pioneer (1830- 1875).” East Side Of The Red. Winnipeg: Inter-Collegiate Press, 1984.