The C-l-L contact dates back to the early part of 1929 when a Mr. Loftus of the firm “Aikins, Loftus and Aikins” approached the Council of the Municipality of St. Clements to discuss the purchase of a 1200 acre tract of land just south of the Village of East Selkirk. By August, 1929, Mr. Loftus stated they (CIL) intended erecting buildings and a plant for the purpose of manufacturing explosives of all kinds. They had considerable discussion regarding assessment. Mr. Loftus suggested that C-l-L be assessed at the 1929 land value rate in the area while the proposed buildings should be exempt, same as farm buildings. Council left C-I-L should get some concessions but that exemption was asking for too much consideration. Finally, a resolution was passed fixing the C-l-L assessment at $100,000 for a period of 12 years with the company to pay 100% for school purposes and 40% for municipal.

Also at this time Council agreed to close up the road on Lot 97 (Parish of St. Clements) and sell same to C-l-L for $100 per acre, and St. Clements was to pay for all improvements, about $300. lt was then that St. Clements agreed to move the two-mile road east to the CPR. With the C-l-L to pay the difference in acreage ($50 per acre) as well as survey and legal costs to get the legislation passed to ratify council’s action.

By early January, 1930 By law No. 402 was read to authorize an agreement between CIL and the municipality of St. Clements with respect to a “certain industry” to be established in the municipality.

Nothing much happened during 1930 and toward the end of Sept. of that year a committee of Council was formed to meet with C I L with the view of “getting them to put contract into effect” . ln a memo to Mr. Loftus dated Oct. 24, 1930 the Council urged C-l-L to commence construction as soon as possible as the unemployment situation in St. Clements was very acute and they were looking forward to some relief from the C-l-L works. Thos. Bunn, Sec Treas. of the municipality also informed Mr. J.S. Morrey of CIL of the urgency and need of work in this area and that he had contacted the Star Hotel in East Selkirk and the hotel was prepared to lodge at least l2 men. The Board and Room would be at the rate of $9.00 per week, per man. Thos. Bunn also stated that the company should have started operation about Sept. l5 and that it was going to be a very difficult winter for many people to make a living. The company had commenced brushing and clearing earlier in 1930 but by 1931 (and in view of the business and financial conditions facing it) was unable to start the plant or operations. Because the agreement stated it would start earlier, C-t-L paid a penalty fl $2,500 for an extension of time on the agreement and starting date. This was l9o based on the initial plant investment of some $250,000.

Mr. Loftus, still representing CIL interests, returned to Council each year asking for some relief in taxation and a reduction in assessment. Finally, in January 1934 the taxes were reduced and based on $75,000 and by November 193,1 By-law No. 496 was passed to confirm the compromise.

April, 1934 was the month that C-l-L authorized the news releases across Canada announcing a new explosives plant at East Selkirk, Manitoba. The new plant was to be known as “Brainerd Works”, and used for the manufacture of commercial high explosives. The plant was named after Dr. Thomas Brainerd, a pioneer of powder manufacturers in the Dominion. Also, one of his sons, Winthrop Brainerd, was Vice-President of C-l-L at the time.

The company admitted that plans for the construction of this unit were made as early as 1929, but operations had been postponed owing to the depression. However, progress in the development of mining activities in the Middle West led the C-l-L board of directors to authorize construction. It was hoped that the manufacture of explosives at this strategic point would reduce haulage from the distance of about 1800 miles to between 600 and 700 miles. Mr. Arthur Blaikie Purvis, President and Managing Director of C I-L also made public in 1931 that the explosives factory was expected to cost about $250,000 and give employment to about 25 men, at the outset.

ln an article carried in the “Contractor” in Nov. Dec. 1934, it was pointed out that “Brainerd Works” was a development of unusual interest, not only from a structural standpoint, but also because it represented a concrete expression of faith in the immediate future of the west.

In describing the 1200 acre site in 1934 the visitors were particularly impressed with the extreme precautions building against danger from friction or static, and against fire or electrical storms. All this called for the thorough grounding of the buildings, the use of brass and copper instead of iron and steel, even in such items as door hinges. Other safety precautions included the use of sections of hardwood for rails rather than steel on the narrow gauge track as well as safety windows, sand filled barricades and the location of motors, switches and other apparatus. all our.ide the building..

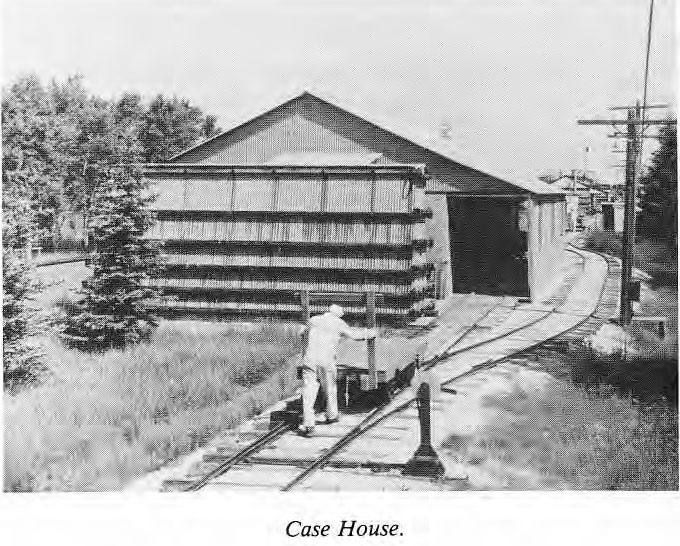

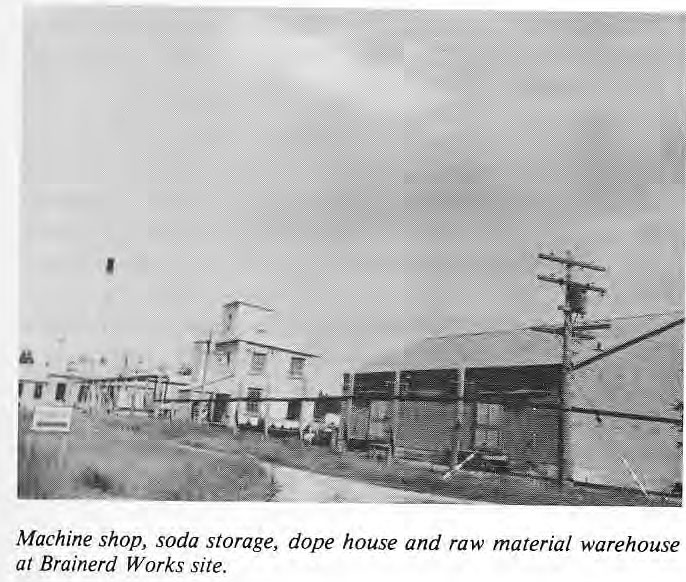

By December, 1934 the company had constructed 17 buildings in all. The group included an office, storehouse, a dope house (for the rising of nonexclusive ingredients) power house, shops, change house, a hell house. miring house. .cartridge house a packing house and 5 magazines.

Regulations controlled the distance between the buildings, the quandaries of ingredients allowed in each building, the number of employees in each building and the methods used in operation.

The plant, like other explosive factories, operated under a yearly license.

Most of the buildings with the exception of the office were constructed of galvanized iron, the latter being specially prepared and having a two-ounce zinc coating.

All the pier foundations were placed down to the blue clay at a depth of about 7 feet. All sills and joists were creosoted B.C. fir. All buildings that held explosives were placed at least 300 feet apart and projected by sand-filled barricades. All buildings were thoroughly grounded, 147 ground rods eight feet in length being used. On the average there were l2 rods to a building.

The first of the buildings to which special attention might be drawn is the office. lt was a one storey frame structure accommodating a storehouse, first aid room and three offices. Fibre board insulation was used in the interior as well as hardwood for the floor.

The next building was a store house of heavy frame construction, in which 6″ x 6″‘s were used. The exterior was galvanized iron. The entire floor was concrete, asphaltic strips being used in the expansion joints. Two sliding doors were provided for incoming materials from the standard gauge spur track, and on the opposite wall were two more doors opening directly to the narrow. gauge track.

Next in line was a group of skids for the temporary storing of materials received in steel drums, and for their transfer from the standards to the narrow gauge railroad.

The soda store was one fl the largest buildings of the group. In this building rain forced concrete was used for floors and buttressed walls to a height of five feet. The roof was high pitched and built at the angle of repose of nitrate of soda. A screw conveyor, having a diameter of 16″ delivered the sodium-nitrite from the hopper, into which the cars were unloaded, to a penthouse, from which it was in turn conveyed by another screw mounted on the ridge and which discharged it for the length of the building from.1 outlets. The motor operating the con veyors was located it the penthouse. Sodium nitrate was delivered from storage to the dope house by a third screw conveyor.

In the dope house, the main bucket elevator delivered the main ingredients to a third floor. Located in the basement was the drive, the elevator boat, into which nitrate of soda from storage was delivered and also a condensate pump. The discharge from the bucket elevator was equipped with a magnetic separator. The equipment included a Toledo print weight scale, which registered exact amounts of ingredients added for accurate recording. The material, as each batch was weighed out, was p[t down through a screen equipped with an air vibrator and then transported to the mix house in fibre “Roving” cans with canvas covers. In no part of the dope house was woodwork exposed, the building being entirely concrete, steel and brick. The roof, made of lumber, was lined with sheet metal. A fire ladder was placed on the outside and the building contained a sprinkler system. The entrance was covered and it was hot water heated.

Next in line was the box storage building made of heavy frame and galvanized iron construction with a heavy No. I maple floor

The power house had 2 hot water boilers and I steam boiler of l5 lb. rating. These were hand fired and equipped with forced draft. The steel stack was 70 feet high with a 24″ diameter, and was well guyed.

The pump room had 2 motor driven centrifugal pumps for circulating hot water through the heating system and also one emergency gas driven pump for the same purpose. The water was supplied from a 300 foot well by a Pomona pump into a reservoir with a capacity of 53,820 gallons and was located west of the power house. From the reservoir, water was led into a suction pit in the pump room then driven throughout the plant by a motor driven centrifugal pump. In addition, there was a fire pump with a 500 gallon per minute capacity. Also located in the pump room was a switch board. Power was brought in from the Wpg. Elec. lines on the west bank of the Red River and was reduced from 2200V to 550V for the motors and I l0 for the lighting system.

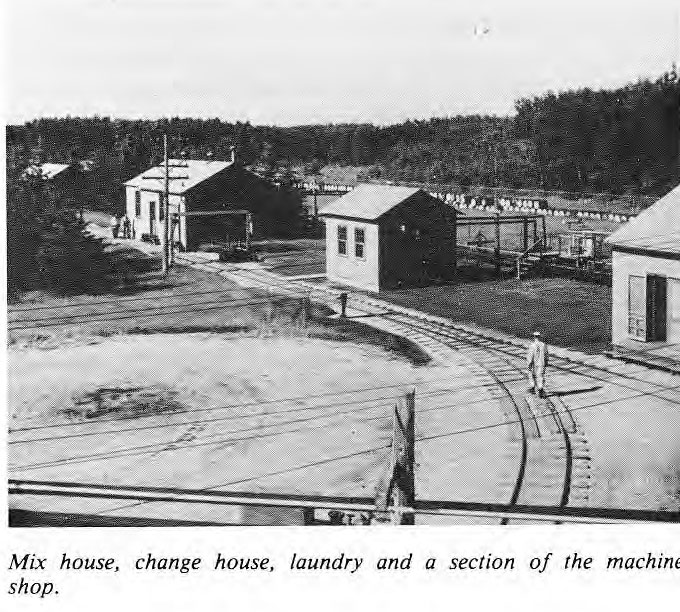

Adjoining the pump room was a general purpose repair shop and a change house. One room was equipped with steel lockers, tables and benches, while in the other room was sinks. toilets and showers. The floors in the boiler room and pump room were concrete while the repair shop floors were hardwood. The change house was cement over hardwood.

Two hot water pipes measuring 2300’served the power plant. Practically all joints were welded with as few pipe fittings as possible. The pipe lines were covered with 85 9o magnesia covering and then heavy roofing paper wound with copper wire.

All outside lines were suspended from poles set l2′ apar1. They were suspended by steel clamps attached to grabber iron held by wood or pipe cross arms. There were 2 sets of expansion joints. The steam line was insulated in the same way. Running a distance of about 1200′ was the airline of 2″ pipe on which were 2 receivers,

The shell house was a frame building with concrete floor, corrugated iron outside and flat galvanized iron inside. It had 2 rooms, one for storage of paper and the other equipped with machinery for the making and printing of shells as well as equipment for impregnating the shells with paraffin. A narrow gauge spur came right into the house, which permitted shells in wooden crates to be loaded. The building had a sprinkler system and was the main consumer of steam by reason of the handling of paraffin.

The change house included the powder line foreman’s office, a store room for powder machine parts and a change room for the use of employees within the explosive area.

Men working in the explosive area were required to wear special clothing with no metal buckles or buttons, no cuffs on the pants. Pockets were such that allowed a hanky or notebook but no penknife or coins etc. The footwear worn inside could not be worn elsewhere. Visitors had to put on rubber footwear that had not been outside. This was a safeguard against grit or sand being tracked in that might cause friction. On the approach of a thunderstorm, all operations ceased and the men retired to a safe distance. As well, all buildings, motors, and the electrical equipment were thoroughly grounded with static removed from drive belts.

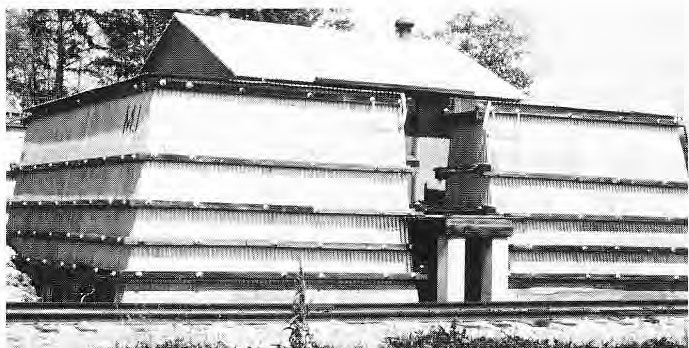

The first group of buildings in the explosive area were similar and placed 300’apart. There was the mix house, cartridge house and packing house. All three were frame construction, on concrete piers, corrugated iron outside, insulating wall board inside with hardwood floors. The cartridge house had a linoleum floor. All the buildings had safety windows for quick exit which resembled double French doors, opening from the inside and barely secured. Hinges were brass with brass pins and brass screws. The glass was double paned with one being ground glass to prevent direct sunlight from falling on the powder.

All the electric lights were enclosed and recessed in boxes covered with glass accessible only from outside the building. All conduits and switches were placed outside the buildings. No steel or iron was exposed at any point likely to come in contact with explosives and for that reason all metal was generally brass or copper. Motors were located in separate detached buildings, except in the case of the mix house where the driving motor was underground, enclosed in a concrete pit. This was used to drive the mixing machine, a large wooden bowl lined with rubber, in which operated two chaser wheels. On the narrow gauge track passing through the covered entrances and from a point 20’past the buildings, oak or maple were used rather than steel for the rails. The door jambs to a height of 4′ were faced with rubber. Loose powder was conveyed in wooden boxes, provided with wooden wheels.

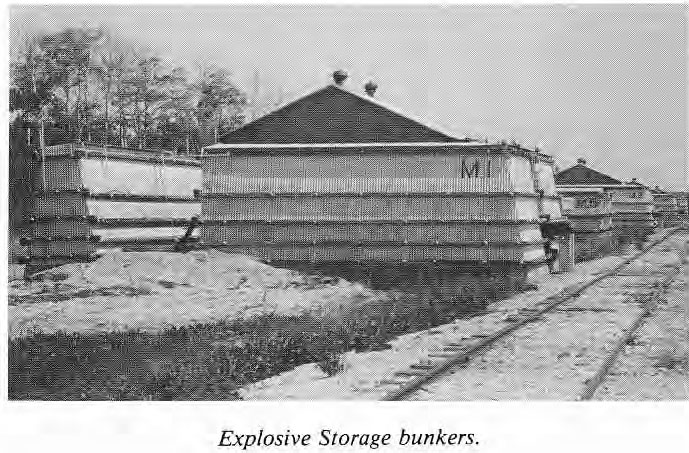

On 2 sides of each of these buildings were sand filled barricades holding from 75 to 80 tons of screened sand. ln the construction of the barricades, a concrete curb was provided on all four sides. On this was raised a wooden frame work which served as temporary support for the corrugated iron and the creosoted “whaling” strips. The barricades were filled by hand.

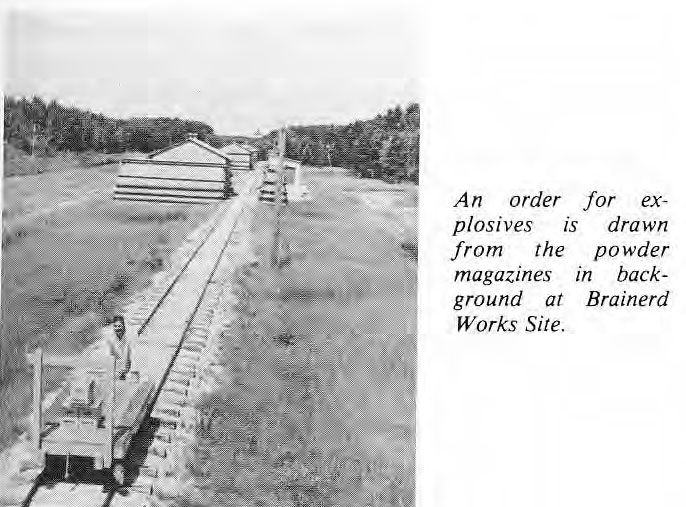

Further down the line were four 25 ton dynamite magazines, and one steel magazine used for detonators. They were all of frame construction covered with galvanized iron. The floors were of B.C. fir and the interiors were sheathed with B.C. fir “V” joints. The roof was 7/8″ tongued and grooved, covered with roofing paper and then covered with corrugated iron. The magazines were surrounded on all four sides by the barricades.

For protection against bush or grass fires in the explosives area, there were t hydrants each having a metal box containing a coiled 150 to 250′ hose which was at all times connected to the hydrants.

A large quantity of gravel was used at Brainerd totaling 5,500 cu. yards, being used for aggregate, the narrow gauge tramway as well as for the barricades.

The company owned some 4,000 feet of standard railway as well as the 3600′ of the narrow gauge wooden railway. All the ties were B.C. fir, creosoted. The ties for the narrow gauge being 6″ x 6’and the 20 pound rail was used at a gauge of 30″.

The whole Brainerd plant was designed by the Engineering Dept. of C-l-L and was constructed under the supervision of E.E. Bard of the Explosives Division. The special powder machinery was built at the C-l-L shops. The general contractor was Carter-Halls-Aldinger Co. Ltd. of Wpg., and no subcontracts were let.

The first high explosive manufactured at Brainerd was on Dec. 10, 1934 and consisted of one 1000 lb. mixing of 4090 Polar For cite Gelatin. On Dec. 19, 1934 one l400lb. mixing of 6090 Polar For cite Gelatin was processed. The interval between Dec. l0 to 19th, being occupied in the completion of necessary construction detail in the explosive buildings and in the training of the crew on dummy powder. Processing of 6090 Polar Forcipes Gelatin was attempted on Dec. 20th, but difficulty was encountered in the drive and clutch on the cart ridging machine, These conditions were corrected and an actual start on operations was obtained on Dec. 21, 1934 when 5 mixings were processed for a total of 134 cases.

The first invoice dated Dec. 7, 1934 was for 4 cases of 60% Polar For cite Gelatin with no size shown. This would be powder transferred from the old Oak bank magazine and not made at Brainerd.

Probably the first Brainerd shipment (powder) was one case of 60q0 Polar Forcite that went out on Dec. 26, 1934.

It was understood that the new Brainerd Works would supply high explosives to most of the territory west of the Great Lakes.

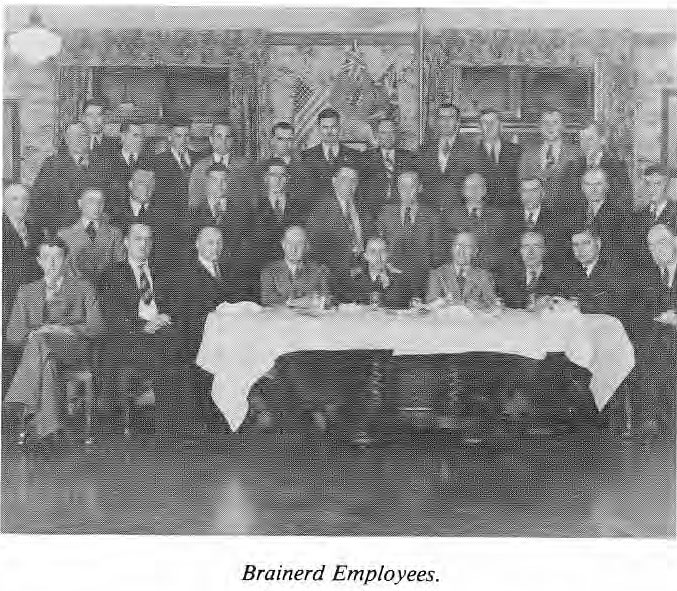

The first works Manager at Brainerd was Mr. C.S. Hannen who had transferred from Beloeil, Quebec. Mr. Hannen was a graduate in chemistry from McGill University and had ll years with the C-l-L Explosives Division. The Asst. works Manager was Mr. W.D. Irwin, a graduate in Chemical engineering from Toronto University and had been with C-I-L since 1929. The Chief Clerk was Mr. J. Keddie, a man with l9 years service with C-I-L.

The three C-l-L plants at Beloeil, Nobel and James Island had looked after all explosives business in Canada until 1934 when the smaller explosives plant was erected at East Selkirk. By January 1935, Brainerd was supplying explosives to extreme Western Ontario as well as Northern Manitoba Mines.

The East Selkirk plant was unique in that it had no acid and no nitroglycerine line. A high strength gelatinous explosive was manufactured at Nobel or Beloeil and was shipped to Brainerd where it was reworked, with added ingredients, to produce a lower strength explosives grades,30-60%.

In January 1935 the company employed about 30 persons, practically all residents of the municipality of St. Clements, and their monthly payroll totaled about $2,000. Much of their raw materials and finished products were being shipped by highway.

ln the summer of 1935 the Works Manager at Brainerd informed Council that C-l-L planned to make shipments by water. To facilitate this C-l-L had a road constructed on River Lot No. 87 from Henderson Highway to the Red River. Along with this C-l-L had constructed dock facilities and purchased two barges.

ln the fall of 1935, C-l-L management wrote to Council urging the municipality to keep Henderson Highway open and clear of snow during the coming winter. Council was short of funds and hard pressed to find the revenue needed to meet this type of request. St. Clements met with the Hwy. Commissioner and attempted to get some financial assistance, but to no avail. In all fairness to St. Clements, it should be intentioned that the depression had deepened and the weight of unemployment and relief weighed heavily on the municipality. This was a time when local governments in Manitoba were driven to the brink of bankruptcy. Also the C-l-L financial statement showed lower profits, as did many other manufacturing concerns around the country.

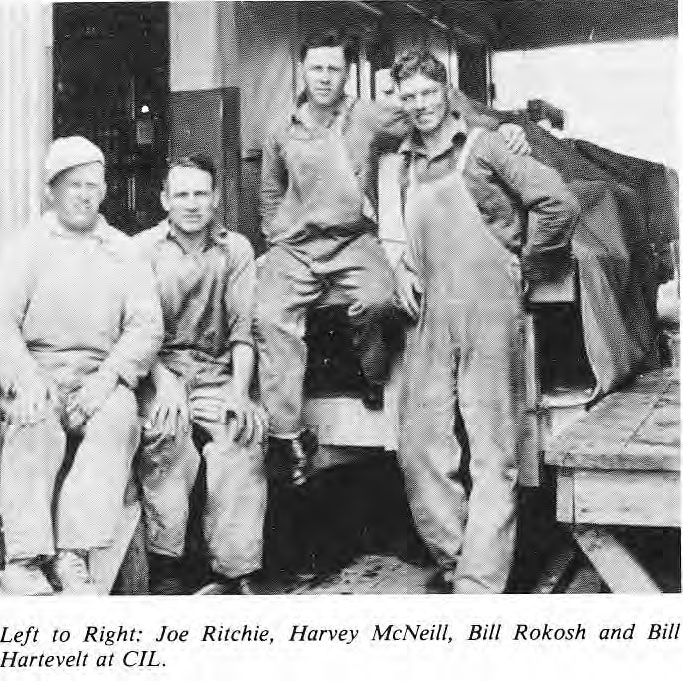

The Brainerd site enjoyed over I 1 years of accident free operation. This record was shattered by tragedy on Aug. 29, 1945, at 2:30 pm. when three men were instantly killed in an explosion in the gelatin cartridge house. The three men killed were: William Rokosh aged 34 years, Emil B. Malmstrom aged 35 years and John Drobot aged 28 years. Three men in the prime of life. No other workers were in the building at the time of the blast and no other workers on the site sustained any injuries. It was stated that the part of the galvanized steel building in which the explosion took place, plus the machinery housed there, were scattered for hundreds of yards by the blast. Arthur Macfie, who was in the C-l-L field south said it looked like a mushroom in the air and that 2 x 4’s flew in the air and stuck like arrows upright in the ground. Arthur stated that the fence on the west side blew flat down by the force.

The explosion occurred when the three man crew had completed punching cartridges of 30% Forcite. About 100 lbs. of Forcite had still to be removed from the building when the explosion occurred. Plant officials at the time said it was fortunate that the majority of Forcite had been removed previously. The three men had been clearing the machine prior to punching in a 40% powder.

Major McNaughton, Plant Manager, along with his Plant Foreman, Sam Rowley, had quite a fight with fires which had caught in the grass following the explosion and were being fanned by a north wind toward the cartridge storage house, some 100 yards away where a very large quantity of explosives was stored. Major McNaughton paid tribute to the men for their efficiency and coolness in helping avert further disaster, “every man knew his job and did it automatically without a hitch”.

The total loss was estimated at about $50,000 and production was interrupted for several days.

An inquest was opened Aug. 31, 1945 but the jury was unable to establish the cause of the explosion. Major McNaughton had testified that the blast could not have been caused by either the machinery or static electricity. The inquest was under the direction of W.H.G. Cibbs and was adjourned until Sept. 6, 1945 and finally concluded during an evening meeting at the Council chambers.

When interviewing Sam Rowley during 1982 with respect to the 1945 disaster, he said, “it was a puzzler as to what really happened and perhaps we will never know” .. “l was in the gelatin cartridge house less than two minutes before the blast and operations were normal at the time of the visit and I had. just reached the packing house when I heard the explosion.” Sam went on to say that they were always careful about the safety end of the operation …” you had to change your clothes on the job site right down to your safety boots. The company supplied and laundered the clothing, when you finished your shift you stripped and showered before putting your own clothing back on … if you were caught ignoring the safety rules you would probably be fired on the spot. Lf you wanted a smoke you had to wait for your lunch break and went down to the end building (main office) for your cigarette … you really had to know what you were doing in that place … for instance you were not supposed to run, just move slowly from place to place, and be especially careful in some areas such as when you were shovelling where the shells were mixed and made,” said Sam.

The CNR tracks came right into the C-I-L compound and, according to sources, the CNR used to throw off sparks that ruined many a hay crop along the route. Those sparks that were visible from the engines used to cause fires and caused C-[-L workers a lot of concern.

There were several women working at Brainerd at one time and their main duty was filling up shells, placing them in 50 lb. crates ready for shipping. Sam Rowley, who is now 82 years old, remembered “they were great workers and it was good for us boys having the women around, it made us watch our language and actions. ” On Dec. 11, 1959, the Brainerd works celebrated its 25 years of operation. The anniversary was commemorated by a dinner for employees, retired personnel, their wives and guests. One of the highlights of the celebration was the presentation of watches as 25 year service awards to H.A. McNeill, Michael Nadwidny, Samuel Rowley, William Van Hartvelt and Arnold Flett. who had all been employed in the plant since its inception. Among the invited guests, it is interesting to note, were: E. Schreyer, MLA, Mayor Massey of Selkirk and Reeve Max Dubas of St. Clements. At the time of the 1959 anniversary, the Brainerd Works had won l0 awards for their safety program, including the highest one, the “C-l-L Prize,” for which it had qualified three time. in succession.

Eleven years later a news release dated June 4, 1970 stated that:

“The Brainerd explosives plant of C-l-L in East Selkirk would cease high explosive manufacturing operation on Sept. I l, 1970.” lt went on to say that the plant would,” continue to be utilized as a magazine for storage and warehousing of explosives and blasting accessories and for the limited manufacture of some blasting agents” The reason given was that, “current requirements of the market made the changes necessary. ”

The C-l-L plant at East Selkirk had been manufacturing high explosives and blasting agents for the mining and construction industries for more than 35 years. C-l-L representatives indicated that the major trend in the mining industry by mid-1970 was to supply products from on-site plants located at the mine itself or adjacent to it. By 1970 two C-l-L on-site plants were brought into operation in Manitoba, at Thompson and Pipe Lake, and a third was located at Bruce Lake in Ontario, near the Manitoba border. These plants were able to provide the more rapid service required by customers and this is what contributed to the major drop in production at the Brainerd plant.

Some l6 employees were affected by CJ-L’s decision to curtail manufacturing at Brainerd. These employees were promised employment at other C-I-L locations. lf they didn’t wish to relocate, C-l-L stated the company would help in other ways such as seeking alternative positions, placement retraining or other assistance. C-I-L provided a relocation allowance to the Brainerd employees who moved to other C-I-L plants in Canada.

Those who did not wish to move received a separation allowance,

The company promised special pensions for those longer service employees who were not placed within the company.

Soon, there were only three men left working at Brainerd, two full time employees (Gordon Swain and Ken Jenkinson) and one part time (Mike Fiwchuk).

By Sept. 1970 the manufacturing operations for nitroglycerine based explosives had ceased at Brainerd. Therefore, the following buildings were taken out of service and were boarded and locked:

- S. 4. Dope House

- S. 6. Box Storage

- S. 1 l. P.L. change house, office and Laboratory

- S. 15. Spare Material Shed

- S. 17. Laundry

- S. 19. Shell House

- S. 30. Auxiliary Boiler House

- S.32. Warehouse.

- P1 Gelatin Mix House – plus Fan and Motor House.

- P2 Gelaten Cartridge House – plus fan and motor house.

- P3 Pack House and Dough Room.

At the end of Nov. 1970 the St- Works office and Stores Building along with S.5, the soda and AM Store, were removed from service. However, the Magazines continued to be used for storage of explosives and building P.6 remained in operation for the manufacture off blasting agent.

The property was reassessed based on this information and Business Roll No. 20 “Explosive Mfg. RL 89/104 was adjusted to reflect this change. Effective Oct. I , I 970

the roll read a change from $ 15,540 to $8,040.

Then, only two men were left working until 1978 when Gordon Swain was laid off and Ken Jenkinson remained for another 6 months. Ken had worked for C-I-L for about 32 years and finally retired at age 55 in 1978. From 1978 to the present time this plant site has been operated from the Wpg. Office of C-l L.

Prior to the wind down of operations C-l L kept four watchmen on the site, 24 hours per day, for security as well as to keep the boilers going at about l5 lb. pressure. Under the Explosives Act and changes at Brainerd, this security was no longer required, according to officials who administer the Act.

Over the years the Brainerd crew befriended two dogs one nicknamed “Stupid” … he was a St. Bernard, brown and white in colour and rather clumsy, hence the name.

The other was a Black Labrador who, so the story goes, had been poisoned. The boys rushed him to the Vet, who saved the dog and it never left the site after its recovery.

The boys shared their lunches with the two pets. Blackie never barked but guarded the gates.

The Brainerd Works operated two tenant houses which were located within the Town of Selkirk on Eveline Sr. No. 282 and No. 243. The company also owned two barges, one of which was sold and the other ended up in the slough and was finally destroyed. When the plant was in full operation, they made use of a two-ton truck and 3 / 4 ton truck, both owned by C-l-L.

When the Cordite Plant in TransCanada was built, some of the Brainerd personnel were seconded as advisors to artist in the initial building and organization.

During 1982 the company removed all buildings from the site with the exception of one warehouse and the magazines (bunkers). The old main office building was purchased and moved up to Victoria Beach for future use as a cottage. Some of the buildings had been removed earlier by tender.

The grounds were neutralized by setting off explosives at strategic areas within the property boundary … this clears the area so that future use of land can be cycled with relative safety.

The Dept. of Energy, Mines and Resources (Explosives Division) at Ottawa have regularly inspected Brainerd and have reported generally excellent conditions on site, and on most occasions that “it is a pleasure to find an installation to inspect like Brainerd where one does not find it necessary to constantly draw to the attention of the escort, various deficiencies and irregularities.”

The C-I-L representatives and the R.M. of Sr. Clements maintained a good working relationship over the years. The plant commenced operations at a time when employment for our residents was badly needed and continued to provide employment opportunities for some 36 years, up until Wpg. assumed full responsibility

for Brainerd in 1970.

We decided to write a fairly comprehensive story about Brainerd (C-l-L) not only because it served a local need by way of employment for over one half century, but because of the role it played in the development of the mid-west. Also, it brought to Manitoba a new industry which, by its very nature, introduced features of building safety and accident prevention entirely novel to this Province at the time.

We hope the photographs of the 1934 site as well as the 1935 crew will stir old memories and we have included some 1982 scene. of the.ite for comparison.

In conclusion, C-l-L took decisive action in 1970 due to economic factors brought about by changes in the market, and did so reluctantly, with due consideration for the needs of the employees affected.

submitted by CIL/slh